CSC/ECE 506 Spring 2015/8a ds

Writeup:https://docs.google.com/document/d/1wVsWId15M0czXs4-9zu7D65UdQy38hK8xfcle9bft7s/edit#

Old version:http://wiki.expertiza.ncsu.edu/index.php/CSC/ECE_506_Spring_2013/8a_an

Introduction

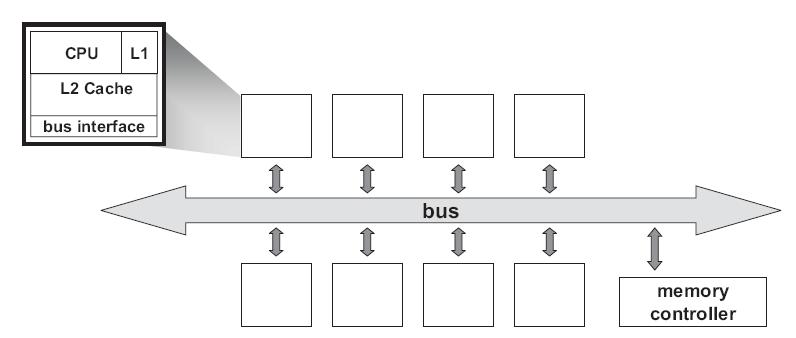

Symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) involves a multiprocessor computer hardware architecture where two or more identical processors are connected to a single shared main memory via system bus. An SMP provides symmetric access to all of main memory from any processor and is the building block for larger parallel systems.

If each processor has a cache that reflects the state of various parts of memory, it is possible that two or more caches may have copies of the same line. It is also possible that a given line may contain more than one lockable data item. If two threads make appropriately serialized changes to those data items, the result could be that both caches end up with different, incorrect versions of the line of memory. In other words, the system's state is no longer coherent because the system contains two different versions of what is supposed to be the content of a specific area of memory. Various protocols have been devised to address the issue of cache coherence problem, such as MSI, MESI, MOESI, MERSI, MESIF, Synapse, Berkeley, Firefly and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dragon_protocol Dragon] protocol. In this wiki article, MSI, MESI, MESIF, MOESI and Synapse protocol implementations on real architectures will be discussed.<ref>Cache Coherence</ref>

MSI Protocol

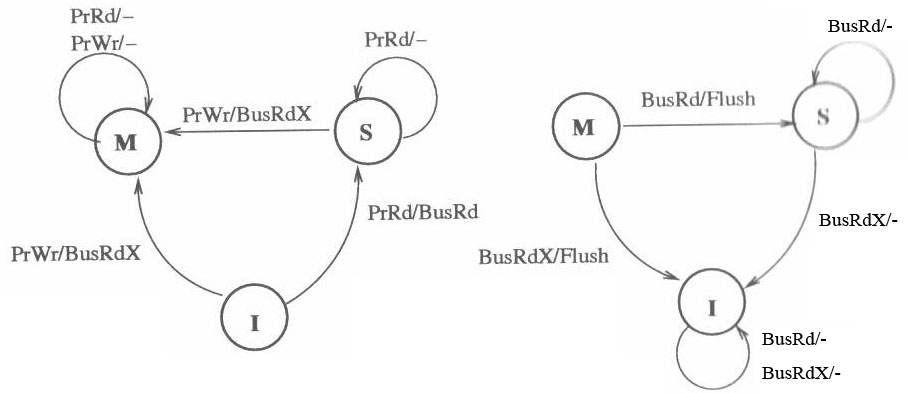

MSI protocol is a three-state write-back invalidation protocol which is one of the simplest and earliest-used snooping-based cache coherence-protocols. According to this protocol, a cache block can be in one of the following three states: Modified (M), Shared (S) or Invalid (I).

- Modified state indicates that the variable in the cache has been modified and therefore has a different value from that found in the main memory. A cache line in this state thus needs to be written back to memory during eviction.

- Shared state indicates that the block exists in one or more caches, and is clean, implying that its value is consistent with the one in main memory. So a cache block in this state can be evicted without having to write it back to the main memory.

- Invalid state indicates that the cache block is invalid.

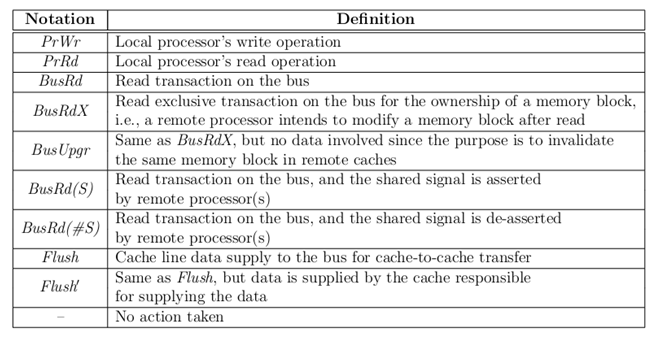

In MSI protocol, processor requests to the cache include:

- PrRd: Processor requests read to a cache block.

- PrWr: Processor requests write to a cache block.

In MSI protocol Bus-side requests include:

- BusRd: BusRd transaction is generated by a PrRd that misses in the cache, and the processor expects a data response as a result. The cache controller puts the address on the bus and asks for a copy that it does not intend to modify. The memory supplies the data, but when the corresponding block is present in a cache in M state then the processor flushes the data to the requester.

- BusRdX: BusRdX transaction is generated by a PrWr to a block that is either not in the cache or is in the cache but is not in modified state. The cache controller puts the address on the bus and asks for an exclusive copy that it intends to modify. The memory system provides the data. All other caches are invalidated. Once the cache obtains the exclusive copy, the write can be performed in the cache.

- Flush: Flush is a snooped request that indicates that an entire cache block is written back to the main memory by another processor.

The MSI states under different conditions are shown below:<ref>Verification of Hierarchical Cache Coherence Protocols for Futuristic Processors</ref>

The three states in the MSI protocol are used to directly enforce the cache coherence by allowing only a single processor to maintain a cache block in the modified state at a given time, allowing multiple processors in the shared state concurrently and disallowing other processors in the shared state while a processor is in the modified state. In the MSI system, there is a serious drawback that an explicit BusRdX transaction is required for a read followed by a write, even if there are no other shared copies. When a processor reads in and modifies a data item, two bus transactions are generated in this protocol even in the absence of shared copies. The first is a BusRd that gets the cache block to S state, and the second is a BusRdX(or BusUpgr) to invalidate other cached copies. The BusRdX is useless in case there are no other shared copies.

Real Architectures using MSI

MSI protocol was first used in SGI IRIS 4D series. SGI produced a broad range of MIPS-based (Microprocessor without Interlocked Pipeline Stages) workstations and servers during the 1990s, running SGI's version of UNIX System V, now called IRIX. The 4D-MP graphics superworkstation brought 40 MIPS(million instructions per second) of computing performance to a graphics superworkstation. The unprecedented level of computing and graphics processing in an office-environment workstation was made possible by the fastest available RISC microprocessors in a single shared memory multiprocessor design driving a tightly coupled and highly parallel graphics system. Aggregate sustained data rates of over one gigabyte per second were achieved by a hierarchy of buses in a balanced system designed to avoid bottlenecks.

The multiprocessor bus used in 4D-MP graphics superworkstation is a pipelined, block transfer bus that supports the cache coherence protocol as well as providing 64 megabytes of sustained data bandwidth between the processors, the memory and I/O system and the graphics subsystem. Since the sync bus provides for efficient synchronization between processors, the cache coherence protocol was designed to support efficient data sharing between processors. If a cache coherence protocol has to support synchronization as well as sharing, a compromise in the efficiency of the data sharing protocol may be necessary to improve the efficiency of the synchronization operations. Hence it uses the simple cache coherence protocol which is the MSI protocol.

With the simple rules of MSIprotocol enforced by hardware, efficient synchronization and efficient data sharing is achieved in a simple shared memory model of parallel processing in the 4D-MP graphics superworkstation.

Implementation complexities

In the MSI system, an explicit upgrade message is required for a read followed by a write, even if there are no other sharers. When a processor reads in and modifies a data item, two bus transactions are generated in this protocol even in the absence of sharers. The first is a BusRd that gets the memory block in S state, and the second is a BusRdX(or BusUpgr) that converts the block from S to M state. In this protocol, the complexity of the mechanism that determines the exclusiveness of the block is an aspect that needs attention. Also, in snoop-based cache-coherence protocols, the overall set of actions for memory operations is not atomic. This could lead to race conditions and the issues of deadlock, serialization, etc. make it harder to implement.<ref>Snoop-based Multiprocessor Design</ref>

MESI Protocol

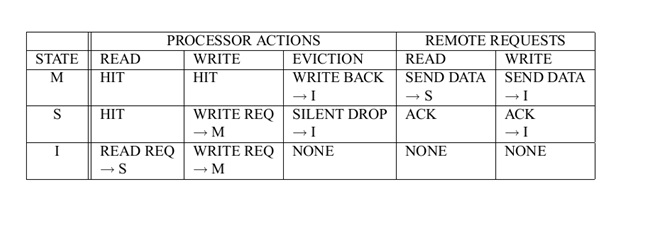

MESI protocol is a 4-state protocol, in which a cache block can have an 'Exclusive' state apart from the Modified, Shared and Invalid state as in MSI protocol.

- Modified : The cache line contains valid data for an external memory location. However, the data in the cache block does not match the data in the external memory since the processor has modiified the data since it was loaded from external memory. A cache that contains a modified line is responsible for ensuring that the data is properly maintained.

- Exclusive : The cache line contains valid data from some external memory location. The data exactly matches the data in the external memory location. Thus the cache block is clean, valid and exists only in one cache.

- Shared : The cache line contains valid data from an external memory location, the data is shared by another cache, and the shared data matches the data in the external memory or the cache line is in write-through mode.

- Invalid : The cache line does not contain valid data from any external memory location.

The advantage of the MESI protocol over the MSI protocol lies in the fact that if the current cache has the Exclusive state, it can silently drop the cache block without issuing the expensive writeback operation. With the MESI protocol, the processor obtains the most current value every time it is required.

In the MESI protocol, the same as the MSI protocol, processor requests to the

cache include:

- PrRd: processor-side request to read to a cache block

- PrWr: processor-side request to write to a cache block

Bus-side request, include:

- BusRd: snooped request that indicates there is a read request to a cache block made by another processor.

- BusRdX: snooped request that indicates there is a read exclusive (write)request to a cache block made by another processor which does not already have the block.

- BusUpgr: snooped request that indicates that there is a write request to a cache block that another processor already has in its cache.

- Flush: snooped request that indicates that an entire cache block is written back to the main memory by another processor.

- FlushOpt: snooped request that indicates that an entire cache block is posted on the bus in order to supply it to another processor. FlushOpt is distinguished from Flush because while Flush is needed for write propagation, FlushOpt is not required for correctness. It is implemented as a performance enhancing feature that can be removed without impacting correctness. It is referred to as an optional block flush cache-to-cache transfer.

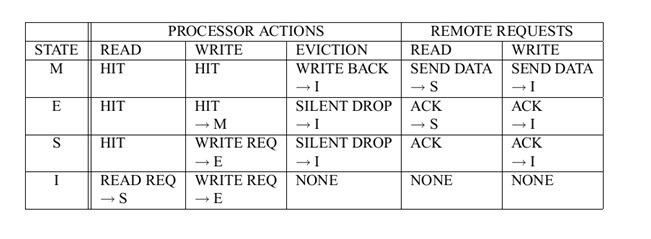

MESI states under different conditions is shown in the figure below:

CMP Implementation in Intel Architecture

Intel's Pentium Pro microprocessor, introduced in 1992, was the first Intel architecture microprocessor to support symmetric multiprocessing in various multiprocessor configurations. SMP and MESI protocol was the architecture used consistently until the introduction of the 45-nm Hi-k Core micro-architecture in Intel's (Nehalem-EP) quad-core x86-64. The 45-nm Hi-k Intel Core microarchitecture utilizes a new system of framework called the QuickPath Interconnect which uses point-to-point interconnection technology based on distributed shared memory architecture. It uses a modified version of MESI protocol called MESIF, which introduces the additional Forward state.<ref>CMP Implementation in Intel Core Duo Processors</ref> (The state diagram of MESI transitions that occur within the Pentium's data cache can be found on page 63 of Pentium Processor System Architecture: Second Edition by Don Anderson, Tom Shanley, MindShare, Inc)

CMP implementation on the Intel Pentium M processor contains a unified on-chip L1 cache with the processor, a Memory/L2 access control unit, a prefetch unit, and a Front Side Bus (FSB). Processor requests are first sought in the L2 cache. On a miss, they are forwarded to the main memory via FSB. The Memory/L2 access control unit serves as a central point for maintaining coherence within the core and with the external world. It contains a snoop control unit that receives snoop requests from the bus and performs the required operations on each cache (and internal buffers) in parallel. It also handles RFO requests (BusUpgr) and ensures the operation continues only after it guarantees that no other version of the cache line exists in any other cache in the system.<ref>CMP Implementation in Intel Core Duo Processors</ref> CMP implementation on the Intel Core Duo contains duplicated processors with on-chip L1 caches, L2 controller to handle all L2 cache requests and snoop requests, bus controller to handle data and I/O requests to and from the FSB, a prefetching unit and a logical unit to maintain fairness between requests coming from each processor to the L2 cache.

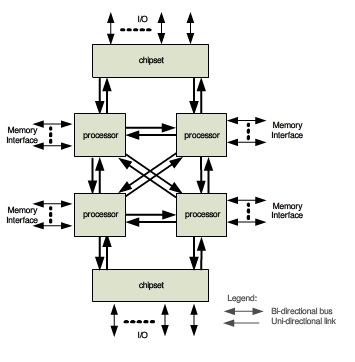

The Intel bus architecture has been evolving in order to accommodate the demands of scalability while using the same MESI protocol. From using a single shared bus to dual independent buses (DIB), doubling the available bandwidth, and to the logical conclusion of DIB with the introduction of dedicated high-speed interconnects (DHSI). The DHSI-based platforms use four FSBs, one for each processor in the platform. In both DIB and DHSI, the snoop filter was used in the chipset to cache snoop information, thereby significantly reducing the broadcasting needed for the snoop traffic on the buses. With the production of processors based on next generation 45-nm Hi-k Intel Core microarchitecture, the Intel Xeon processor fabric will transition from a DHSI, with the memory controller in the chipset, to a distributed shared memory architecture using Intel QuickPath Interconnects using MESIF protocol.

MESI in AMD's AM486DX microprocessors

The Am486 is a 80486-class family of computer processors that was produced by AMD in the 1990s. AMD's enhanced Am486DX microprocessors implement the MESI protocol on systems with write-back cache support. These microprocessors allocate memory in the cache due to a read miss. Write allocation is not implemented.

To maintain coherence between cache and main memory, this protocol is implemented with the following characteristics:

- The system memory is always updated during a snoop when a modified line is hit.

- If a modified line is hit by another master during snooping, the master is forced off the bus and the snooped cache writes back the modified line to the system memory.

After the snooped cache completes the write, the forced-off bus master restarts the access and reads the modified data from memory.A cache line can occupy one of the four legal states (M, E, S, I) which can be indicated by the 2 bits in the tag entry.<ref>AMD-K6 -2E Embedded Processor Data Sheet Publication</ref>

ARM MPCore

The ARM11 MPCore and Cortex-A9 MPCore processors support the MESI cache coherency protocol. ARM MPCore defines the states of the MESI protocol it implements as:

| Cache Line State: | Modified | Exclusive | Shared | Invalid |

| Copies in other caches | NO | NO | YES | - |

| Clean or Dirty | DIRTY | CLEAN | CLEAN | - |

The coherency protocol is implemented and managed by the Snoop Control Unit (SCU) in the ARM MPCore, which monitors the traffic between local L1 data caches and the next level of the memory hierarchy. At boot time, each core can choose to partake in the coherency domain or not. Unless explicit system calls bound a task to a specific core (processor affinity), there are high chances that a task will at some point migrate to a different core, along with its data as it is used. Migration of tasks is not efficiently implemented in literal MESI implementation, so the ARM MPCore offers two optimizations that allow for MESI compliance and migration of tasks: Direct Data Intervention (DDI) (in which the SCU keeps a copy of all cores caches’ tag RAMs. This enables it to efficiently detect if a cache line request by a core is in another core in the coherency domain before looking for it in the next level of the memory hierarchy)and Cache-to-cache Migration (where if the SCU finds that the cache line requested by one CPU present in another core, it will either copy it (if clean) or move it (if dirty) from the other CPU directly into the requesting one, without interacting with external memory). These optimizations reduce memory traffic in and out of the L1 cache subsystem by eliminating interaction with external memories, which in effect, reduces the overall load on the interconnect and the overall power consumption.<ref>ARM</ref>

Other architectures that use the MESI cache-coherence protocol include the L2 cache of the IBM POWER4 processor<ref>IBM POWER4</ref>, the L2 cache of the Intel Itanium 2 processor, and the Intel Xeon<ref>Intel Itanium 2</ref>.

Implementation Complexities

During replacement of a cache block, some MESI implementations require a message to be sent to memory when a cache line is flushed - an E to I transition, as the line was exclusively in one cache before it was removed. In alternate implementation, this replacement message could be avoided if the system is designed so that the flush of a modified /exclusive line requires an acknowledgment from the memory. However, this requires the flush to be stored in a 'write-back' buffer until the reply arrives to ensure the change is successfully propagated to memory.

According to the application, there is a bandwidth trade-off in both these applications. The MESI protocol has greater complexity in terms of block states and transitions. It requires a priority scheme for cache-to-cache transfers to determine which cache should supply the data when in shared state. In commercial implementations, the memory is usually allowed to update data. Like in the MSI protocol, this protocol too has the issues of complexity in issues of serialization, handshaking, deadlocks, etc. Also, the implementation of write-backs necessitates a write-buffer. The bus transactions relevant to buffered blocks must be handled carefully<ref>Discussion of cache coherence protocol implementation</ref><ref>Optimizing the MESI Cache Coherence Protocol for Multithreaded Applications on Small Symmetric Multiprocessor Systems</ref>

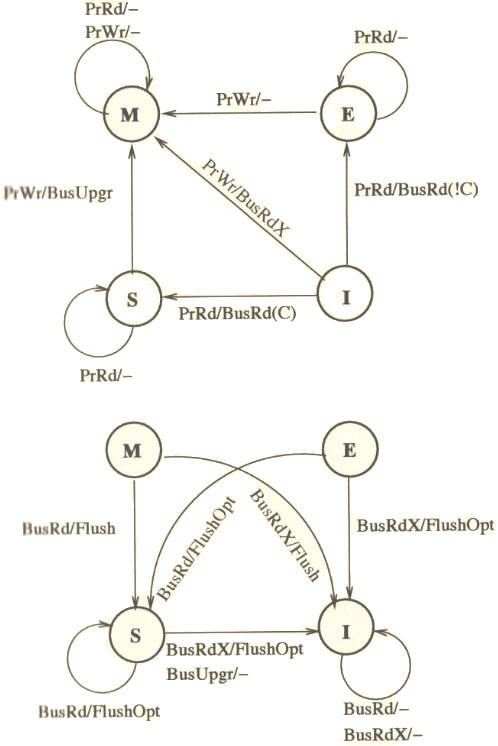

MESIF Protocol

The MESIF protocol is a cache coherency and memory coherence protocol developed by Intel for cache coherent non-uniform memory architectures.The protocol consists of five states, Modified (M), Exclusive (E), Shared (S), Invalid (I) and Forward (F).

The M, E, S and I states are the same as in the MESI protocol. When a processor requests a cache line that is stored in multiple locations, every location might respond with the data. However, the requesting processor only needs a single copy of the data, so the system is wasting a bit of bandwidth. Intel's solution to this issue is rather elegant. They adapted the standard MESI protocol to include an additional state, the Forwarding (F) state, and changed the role of the Shared (S) state. In the MESIF protocol, only a single instance of a cache line may be in the F state and that instance is the only one that may be duplicated. Other caches may hold the data, but it will be in the shared state and cannot be copied. In other words, the cache line in the F state is used to respond to any read requests, while the S state cache lines are now silent. This makes the line in the F state a first amongst equals, when responding to snoop requests. By designating a single cache line to respond to requests, coherency traffic is substantially reduced when multiple copies of the data exist.

When a cache line in the F state is copied, the F state migrates to the newer copy, while the older one drops back to S. This has two advantages over pinning the F state to the original copy of the cache line. First, because the newest copy of the cache line is always in the F state, it is very unlikely that the line in the F state will be evicted from the caches. In essence, this takes advantage of the temporal locality of the request. The second advantage is that if a particular cache line is in high demand due to spatial locality, the bandwidth used to transmit that data will be spread across several nodes.

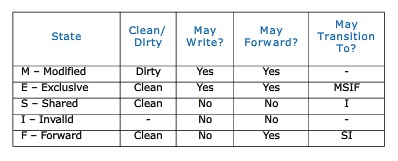

The table below summarizes the MESIF cache states:

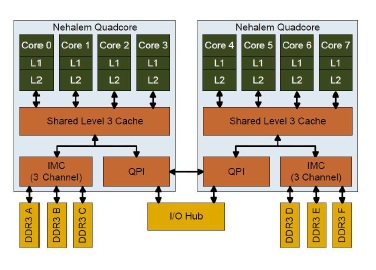

MESIF in Intel Nehalem Computer

Intel Nehalem Computer uses the MESIF protocol. In the Nehalem architecture each core has its own L1 and L2 cache. Nehalem does have a shared cache, implemented as L3 cache. This cache is shared among all cores and is relatively large. This cache is inclusive, meaning that it duplicates all data stored in each individual L1 and L2 cache. This duplication greatly adds to the inter-core communication efficiency because any given core does not have to locate data in another processor’s cache. If the requested data is not found in any level of the core’s cache, it knows the data is also not present in any other core’s cache. To ensure coherency across all caches, the L3 cache has

additional flags that keep track of which core the data came from. If the data is modified in L3 cache, then the L3 cache knows if the data came from a different core than the previous time and that the data in the first core needs its L1/L2 values updated with the new data. This greatly reduces the amount of traditional “snooping” coherency traffic between cores.<ref>Comparing Cache Organization and Memory Management of the Intel Nehalem Computer Architecture</ref>

The cache organization of an 8-core Intel Nehalem Processor is shown below:

MESIF in Intel® QuickPath Interconnect

The Intel QuickPath Interconnect is a high speed packetized point-to-point interconnect used in Intel's next generation of microprocessors introduced in second half of 2008. The narrow high speed links stitch together processors in distributed memory style platform architecture. The Intel QuickPath Interconnect includes the MESIF cache coherency protocol to keep the distributed memory and shared caching coherent during system operation. It supports both low latency source snooping and direct cache-to-cache transfers for low latency.

The Intel® QuickPath Interconnect coherency protocol consists of two distinct types of agents: caching agents and home agents. A microprocessor will typically have both types of agents and possibly multiple agents of each type. A caching agent represents an entity which may initiate transactions into coherent memory and which may retain copies in its own cache structure. The caching agent is defined by the messages it may sink and source according to the behaviors defined in the cache coherence protocol. A caching agent can also provide copies of the coherent memory contents to other caching agents.A home agent represents an entity which services coherent transactions, including handshaking when necessary with caching agents. A home agent supervises a portion of the coherent memory. Home agent logic is not specifically the memory controller circuits for main memory but rather the additional Intel® QuickPath Interconnect logic, which maintains the coherency for a given address space. It is responsible for managing the conflicts that might arise among the different caching agents. It provides the appropriate data and ownership responses as required by a given transaction’s flow.

There are two basic types of snoop behaviors supported by the Intel® QuickPath Interconnect specification. Which snooping style is implemented is a processor architecture specific optimization decision. To over-simplify, source snoop offers the lowest latency for small multi-processor configurations. Home snooping offers optimization for the best performance in systems with a high number of agents.The home snoop coherency behavior defines the home agent as responsible for the snooping of other caching agents.The Intel® QuickPath Interconnect home snoop behavior implementation typically includes a directory structure to target the snoop to the specific caching agents that may have a copy of the data. This has the effect of reducing the number of snoops and snoop responses that the home agent has to deal with on the interconnect fabric. This is very useful in systems that have a large number of agents, although it comes at the expense of latency and complexity. Therefore, home snoop is targeted at systems optimized for a large number of agents.The source snoop coherency behavior streamlines the completion of a transaction by allowing the source of the request to issue both the request and any required snoop messages.The source snoop behavior offers lower latency at the expense of requiring agents to maintain a low latency path to receive and respond to snoop requests. It also imparts additional bandwidth stress on the interconnect fabric, relative to the home snoop method. Therefore, the source snoop behavior is most effective in platforms with only a few agents.<ref>The Common System Interface: Intel's Future Interconnect</ref>

Implementation Complexities

In comparison to the MESI protocol, the addition of 'Forward' state in the MESIF protocol reduces the complexity due to a reduction in the extent of communication between cores. This reduced communication is due to the design of a specific state such that a single cache will respond to all the read requests for shared data. The implementation of write-backs necessitates a 'write-buffer' like in the case of MESI protocol, and the bus transactions relevant to these buffered blocks require careful handling. Though the inclusion of an additional state does increase design complexity, the working of this additional state and the concomitant decrease in communication between cores leads to the overall implementation complexity being similar to that in the MESI protocol.

MOESI Protocol

MOESI is a five state cache coherence protocol with the following states:

- Invalid: A cache line in the invalid state does not hold a valid copy of the data. Valid copies of the data can be either in main memory or another processor cache.

- Exclusive: A cache line in the exclusive state holds the most recent, correct copy of the data. The copy in main memory is also the most recent and correct copy of the data. No other processor holds a copy of the data.

- Shared: A cache line in the shared state holds the most recent and correct copy of the data. Other processors in the system may hold copies of the data in the shared state as well. If no other processor holds it in the owned state, then the copy in main memory is also the most recent.

- Modified: A cache line in the modified state holds the most recent and correct copy of the data. The copy in main memory is stale (incorrect), and no other processor holds a copy.

- Owned: A cache line in the owned state holds the most recent, correct copy of the data. The owned state is similar to the shared state in that other processors can hold a copy of the most recent and correct data. Unlike the shared state, however, the copy in main memory can be stale (incorrect). Only one processor can hold the data in the owned state, all other processors must hold the data in the shared state.

MOESI is a more elaborate version of the simpler MESI protocol and avoids the need to write a dirty cache line back to the main memory when another processor tries to read it. Instead, the Owned state allows a processor to supply the modified data directly to the other processor. This is beneficial when the communication latency and bandwidth between two CPUs is significantly better than CPU to main memory. An example would be multi-core CPUs with per-core L2 caches. While MOESI can quickly share dirty cache lines from the cache, it cannot quickly share clean lines from the cache. If a cache line is clean with respect to the memory and in the shared state, then any snoop request to that cache line will be filled from the memory, rather than a cache. If a processor wishes to write to an Owned cache line, it must notify the other processors that are sharing that cache line. Depending on the implementation it may simply tell them to invalidate their copies (moving its own copy to the Modified state), or it may tell them to update their copies with the new contents (leaving its own copy in the Owned state).

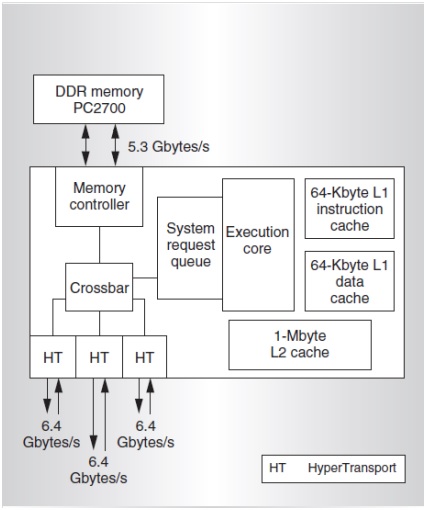

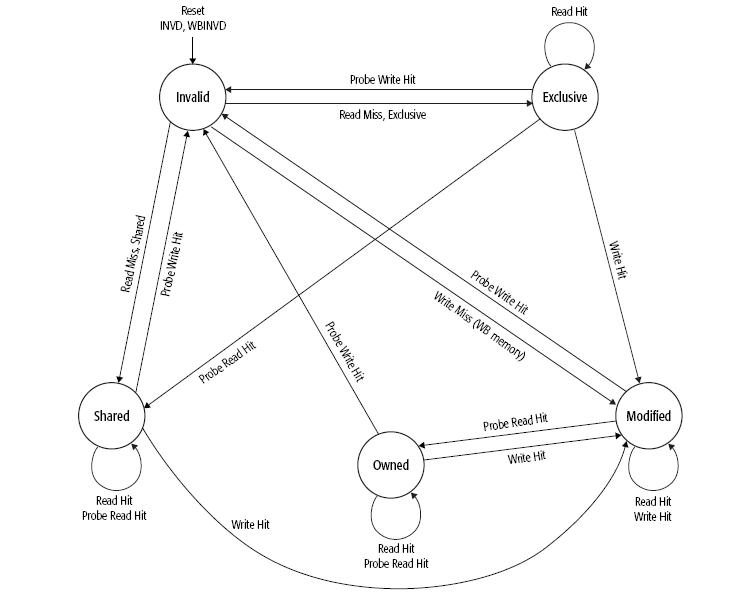

MOESI in AMD64 architecture

The cache-coherency protocol supported by the AMD64 architecture is theMOESI. The figure beside shows the general MOESI state transitions possible with various types of memory accesses in AMD64 architecture. This is a logical software view, not a hardware view, of how the cache line state transitions. Instruction-execution activity and external-bus transactions can both be used to modify the cache MOESI state in multiprocessing or multi-mastering systems. To maintain memory coherency, external bus masters (typically other processors with their own internal caches) need to acquire the most recent copy of data before caching it internally. That copy can be in the main memory or in the internal caches of other bus-mastering devices. When an external master has a cache read-miss or write-miss, it probes the other mastering devices to determine whether the most recent copy of data is held in any of their caches. If one of the other mastering devices holds the most recent copy, it provides it to the requesting device. Otherwise, the most recent copy is provided

by main memory.<ref>AMD 64 Technology</ref>

There are two general types of bus-master probes:

- Read probes indicate the external master is requesting the data for read purposes.

- Write probes indicate the external master is requesting the data for the purpose of modifying it.

The state transitions involving probes are initiated by other processors and external bus masters into the processor. Some read probes are initiated by devices that intend to cache the data. Others, such as those initiated by I/O devices, do not intend to cache the data.

Some processor implementations do not change the data MOESI state if the read probe is initiated by a

device that does not intend to cache the data.

State transitions involving read misses and write misses can cause the processor to generate probes into external bus masters and to read main memory. Read hits do not cause a MOESI-state change. Write hits generally cause a MOESI-state change into the modified state. If the cache line is already in the modified state, a write hit does not change its state. The specific operation of external-bus signals and transactions and how they influence a cache MOESI state are implementation dependent. For example, an implementation could convert a write miss to a WB memory type into two separate MOESI-state changes. The first would be a read miss placing the cache line in the exclusive state. This would be followed by a write hit into the exclusive cache line, changing the cache line state to Modified.

Implementation Complexities

When implementing the MOESI protocol on a real architecture like AMD K10 series, some modification or optimization was made to the protocol which allowed more efficient operation for some specific program patterns. For example AMD Phenom family of microprocessors (Family 0×10) which is AMD’s first generation to incorporate four distinct cores on a single die and the first to have a cache that all the cores share, uses the MOESI protocol with some optimization techniques incorporated.

It focuses on a small subset of computation problems which behave like Producer and Consumer programs. In such a computation problem, a thread of a program running on a single core produces data which is consumed by a thread that is running on a separate core. With such programs, it is desirable to get the two distinct cores to communicate through the shared cache to avoid round trips to/from main memory. The MOESI protocol that the AMD Phenom cache uses for cache coherence can also limit bandwidth. Hence by keeping the cache line in the ‘M’ state for such computation problems, we can achieve better performance.

When the producer thread writes a new entry, it allocates cache lines in the Modified (M) state. Eventually, these M-marked cache lines will start to fill the L3 cache. When the consumer reads the cache line, the MOESI protocol changes the state of the cache line to Owned (O) in the L3 cache and pulls down a Shared (S) copy for its own use. Now, the producer thread circles the ring buffer to arrive back to the same cache line it had previously written. However, when the producer attempts to write new data to the owned (marked ‘O’) cache line, it finds that it cannot do so since a cache line marked ‘O’ by the previous consumer read does not have sufficient permission for a write request (in the MOESI protocol). To maintain coherence, the memory controller must initiate probes in the other caches (to handle any other S copies that may exist). This will slow down the process.

Thus, it is preferable to keep the cache line in the ‘M’ state in the L3 cache. In such a situation, when the producer comes back around the ring buffer, it finds the previously written cache line still marked ‘M’, to which it is safe to write without coherence concerns. Thus better performance can be achieved by such optimization techniques to standard protocols when implemented in real machines.

You can find more information on how this is implemented and various other ways of optimizations in this manual Software Optimization guide for AMD 10h Processors

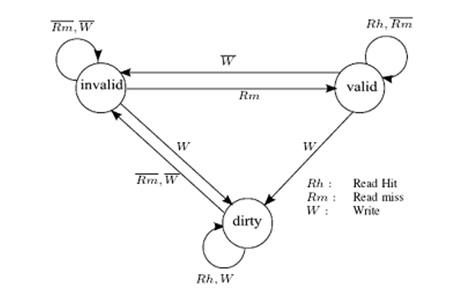

Synapse Protocol

In Synapse protocol, cache blocks are in one of the following states:

- Invalid: Indicates that the block is invalid

- Valid: Indicates that the cache block is unmodified and possibly shared

- Dirty: indicates that the cache block is modified and there are no other copies.

Only blocks in state Dirty are written back when replaced. Any cache with a copy of a block in state Dirty is called the owner of that block. If no Dirty copy exists, the main memory is the owner.

Implementation Complexities

The Synapse Expansion Bus includes an ownership level protocol between processor caches. It employs a non-write-through algorithm to minimize the bandwidth between the cache and the shared memory. This protocol does not require a great deal of hardware complexity. Since an extra bit is added to the main memory to indicate whether a cache has an exclusive(Dirty) copy of the block, this needs to be implemented correctly to prevent malfunction of the protocol.<ref>Synapse tightly coupled multiprocessors: a new approach to solve old problems</ref>

Synapse N+1 multiprocessor

Synapse protocol was used in the Synapse N + 1, a multiprocessor for fault-tolerant transaction processing. The N + 1 differs from other shared bus designs considered in that it has two system buses. The added bandwidth of the extra bus allows the system to be expanded to a maximum of 28 processors. A single-bit tag is included with each cache block in main memory, indicating whether main memory is to respond to a miss on that block. If a cache has a modified copy of the block, the bit tells the memory that it need not respond. Thus if the bit is set, an access to the block fails until the data is written back to memory by the cache with the exclusive copy and the bit is reset. This prevents a possible race condition if a cache does not respond quickly enough to inhibit main memory from responding.<ref>Cache Coherence Protocols: Evaluation Using a Multiprocessor Simulation Model</ref>

Differences between Synapse and MSI Protocol

The Synapse protocol has the following states: valid, invalid and dirty. On the other hand, the MSI protocol has a modified state, a shared state and an invalid state. Since the Synapse protocol has a valid state instead of a shared state, it leads to some differences between the two protocols and how they are implemented.

One difference between the Synapse protocol and the MSI protocol is the state transition that happens when a Bus Read is snooped by a processor for a block in the Modified or Dirty state. In Synapse, it will transition to the Invalid state, whereas in MSI, it will transition to the Shared state. Another difference is that the Synapse protocol does not have any Bus Invalidation transaction. Instead, it only has a Bus Write. Therefore, when a write is issued to a valid block, a Bus Write happens instead of a Bus Invalidate. This means that there are unnecessary memory transactions in the Synapse protocol for this case, which will lead to additional bus traffic. Also, additional latency is incurred by the writing processor since it has to wait for the transfer of the entire cache block to complete before it can resume operation. <ref>An Evaluation of Snoop-Based Cache Coherence Protocols</ref>

Prefetching

With processor speeds continuing to outpace the memory subsystem, the memory operations (cache misses) increasingly dictate application performance. While one typically thinks in terms of data misses and data prefetching, instruction cache misses can also represent a significant performance loss for modern processors. Indeed, instruction misses are usually more expensive than data misses as instruction misses stall the processor pipeline, while a significant proportion of data misses can often be overlapped with other instructions.

For many modern commercial workloads where the instruction working set is sufficiently large to cause significant stalls due to both Level 1 (L1) and Level 2 (L2) cache misses, instruction prefetching schemes can be utilized to reduce the performance impact of these misses. Prefetching schemes speculatively initiate a memory access for a cache line, bringing the line into the caches before the processor requests the cache line, minimizing, or even eliminating, the stall experienced by the processor. Instruction prefetching is not a new topic and a variety of different hardware (HW) and software instruction prefetch schemes have been proposed. However, most modern processors only support very rudimentary HW instruction prefetchers that target only sequential misses.

Furthermore, as the relative distance to memory increases, prefetches must be issued increasingly far in advance. Today, this look ahead distance is in the order of hundreds of processor clock cycles. This necessitates that prefetchers should become increasingly speculative and this introduces new challenges: i) how to identify the direction the application is headed sufficiently early to allow timely prefetches to be issued and ii) although the prefetcher is speculating on program behavior hundreds of cycles in the future, it must be able to do so accurately in order to minimize the prefetch bandwidth requirements and cache pollution. These challenges are even more relevant for Chip Multi-Processors(CMP), where there is potential for inter-core pollution via the shared L2 cache and the per-core bandwidth and cache resources are much more limited.

Due to prefetching, it is possible that the data can be modified in such a way that the memory coherence protocol will not be able to handle the effects. An example of this type of situation is a page-table update followed by accesses to the physical pages referenced by the updated page tables. Because of prefetching there may be problem with correctness. Lets say for example, software wants to change the page table entry for virtual page A from physical-page M to physical-page N. For this to be done, the tables that translate virtual-page A to physical-page M are brought into main memory and its cached copies will be invalidated. Once this is done, the page-table entry for virtual-page A in main memory can be changed by the software to point to physical page N which was initially pointing to physical-page M. Once the page table update is done, software expects the processor to access the data from physical-page N. However, it could be possible that the processor had prefetched the data from physical-page M before the page table for virtual page A was updated. Because the physical-memory references are different, the processor may not recognize them as requiring coherence checking. So now if the data from virtual-page A is accessed, the data from physical-page M might be returned, while it is expected to return data from physical page N.In order to prevent such errors from occurring, the software must use serializing instructions or cache-invalidation instructions to guarantee that subsequent data accesses are coherent.

Popularity of Different Coherence Protocols

The late 1980s and the 1990s saw an increase in the popularity of the MSI protocol and also the Synapse protocol. However, as discussed, the MSI protocol performed better than the Synapse protocol. This can be one of the main reasons why Synapse protocol was supplanted by other protocols in subsequent years. The MSI protocol, on the other hand, continued to gain popularity and variants of MSI were used by systems in subsequent years. Most modern systems still use such variants (eg. MESI, MOESI, MESIF) in order to reduce the amount of traffic in the coherency interconnect.

The Firefly protocol was first used in the DEC Firefly, a shared memory multi-processor workstation that was developed by the Systems Research Center (a research organization which is a subset of the Digital Equipment Corporation) in the late 1980s. The Dragon protocol was used in the Xerox Dragon multiprocessor work station (developed by Xerox PARC). The popularity of Firefly protocol and Dragon protocol seems to have subsided by the mid 1990s.

Summary

The implementation of these cache coherence protocols in write-back caches saves off-chip bandwidth consumption significantly in comparison to write-through caches. The simplest implementation is the three-state MSI protocol. The Synapse protocol is similar to this with an extra bit to indicate whether the cache has an exclusive copy of the block. The extra Exclusive state in the MESI protocol removes the drawback of incurring two bus transactions on a read-write sequence regardless of whether block is stored in only one cache or not in this protocol. This state distinguishes between a block that is clean and exclusively cached versus a block that is clean and stored at multiple caches. Since the extra bus transaction is eliminated, this protocol avoids penalizing sequential programs and highly-tuned parallel programs. However, the MESI protocol incurs additional complexity compared to the MSI protocol due to the addition of the Shared status line and it's associated logic. The addition of the Forwarding state to take advantage of the temporal and spatial locality of the request gives rise to the MESIF protocol. A more complex protocol with better performance is the MOESI protocol which improves on the MESI protocol with an additional Owned state. Since dirty sharing is supported by allowing the dirty block to be shared by multiple caches, a cache flush does not need to update main memory. Compared to the MESI protocol, the MOESI protocol does not reduce the bandwidth usage on the bus but it does reduce the bandwidth use to the main memory. <ref>Parallel Computer Architecture: A Hardware/Software Approach, By David E. Culler, Jaswinder Pal Singh, Anoop Gupta</ref>

Glossary

The terms that have been used are defined below:<ref>Integration and Evaluation of Cache Coherence Protocols for Multiprocessor SoCs</ref>

References

<references/>