CSC/ECE 506 Spring 2012/8b va

Update and adaptive coherence protocols on real architectures, and power considerations

Introduction

In a shared memory - shared-bus multiprocessor system, cache coherency protocol maintains one of the important roles to propagate changes from one cache to the others. But in most of the cases, update and invalidate coherence protocols are the main source of bus contention that can lead to increased number of bus busy cycles, thus increasing program execution time because the processor may stall while its cache is waiting for the bus. To avoid the bus contention this article brings up some high performance multiprocessor based adaptive hybrid protocol strategies.<ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CDcQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fciteseerx.ist.psu.edu%2Fviewdoc%2Fdownload%3Fdoi%3D10.1.1.36.536%26rep%3Drep1%26type%3Dpdf&ei=gQ9lT_uzNKmDsgKOio23Dw&usg=AFQjCNHhVV9CB80kuVKDc-h5hTsicTArJg</ref>

Coherence protocols

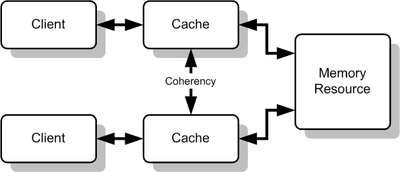

In general terms, a coherency protocol is a protocol which maintains the consistency between all the caches in a system of shared memory. The protocol maintains memory coherence according to a specific consistency model. Older multiprocessors support the sequential consistency model, while modern shared memory systems typically support the release consistency or weak consistency models.

Multiple Caches of Shared Resource

Transitions between states in any specific implementation of these protocols may vary. For example, an implementation may choose different update and invalidation transitions such as update-on-read, update-on-write, invalidate-on-read, or invalidate-on-write. The choice of transition may affect the amount of inter-cache traffic, which in turn may affect the amount of cache bandwidth available for actual work. This should be taken into consideration in the design of distributed software that could cause strong contention between the caches of multiple processors. Various models and protocols have been devised for maintaining cache coherence, such as MSI protocol, MESI (aka Illinois protocol), MOSI, MOESI, MERSI, MESIF, write-once, Synapse, Berkeley, Firefly and Dragon protocol

For the purpose of the main study, this article will focus on the two commonly used coherence protocols: Write-Invalidate (WI) and Write-Update (WU)

Write-Invalidate Protocol

In a Write-Invalidate Protocol a processor invalidates all other processors cache block and then updates its own cache block without further bus operations.

Write-Update Protocol

Interchangeably,in a Write-Uptade Protocol, a processor broadcasts updates to shared data to other caches so other cashes stay coherent.<ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

- Disadvantages of Write-Invalidate Protocol

- Any update/write operation in a processor invalidates the shared cache blocks of other processors, forcing other caches to do the bus request to reload the new data that turns to increase high bus bandwidth. This can be worse if one processor frequently updates the cache and other processor stalls to read the same cache block. For a sequence n that writes in one processor and read from other processor, WI protocol makes n invalidate and n cache block read operations.<ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

- Disadvantages of Write-Update Protocol

- Update protocol is advantageous in this case because it updates only the cache blocks n times. But update protocol sometimes refresh unnecessary data of other processors cache for too long, hence fewer cache blocks are available for more useful data. It tends to increase conflict and capacity cache misses.<ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

Consideration of cache architecture issue

Execution of applications directly relate to the size of cache block too. Some applications execute more quickly with large cache block size because they exhibit good spatial locality where as some applications run better when cache block sizes are small by avoiding migratory data or false sharing between processors. <ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

Using the combination strategy like adaptive hybrid protocol can reduce nature of pathological behaviors of update and invalid protocols. This protocol should be applicable to a wide range of network characteristics and it should automatically adjust its behavior to achieve target goals in the face of changes in traffic patterns, node mobility and other network characteristics.

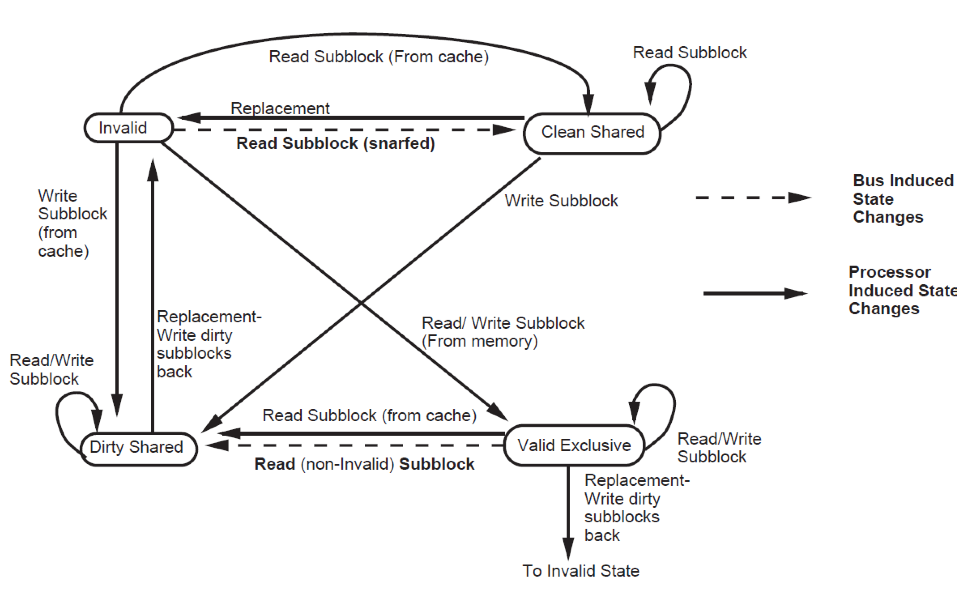

Hardware architecture

Most often, processor architecture maintains the same block size for both memory to cache, cache to memory transfer and coherence. This approach uses different block sizes for transfer and coherence based on application requirements. Normal cache has the following parameters: Capacity(C), Block size (L) and associativity (K). But sector cache divides the cache blocks into subblocks of size “b”. Though a sector cache (C, L, K, b) requires one extra state and some extra bus line to transmit bitmasks corresponding to the status of the subblocks in a particular block compare to normal cache(C, L, K) but maintains the same number of tag and state bits for L. <ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

-

Block states

- Invalid: All subblocks are invalid

- Valid Exclusive: All valid subblocks in this block are not present in any other caches. All subblocks that are clean shared may be written without a bus

- transaction. Any subblocks in the block may be invalid. There also may be Dirty blocks which must be written back upon replesment.

- Clean Shared: The block contains subblocks that are either Clean Shares or Invalid. The block can be replaced without a bus transaction.

- Dirty Shared: Subblocks in this block may be in any state. There may be Dirty blocks which must be written back on replacement.<ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

-

Subblock states

- Invalid: The subblocks is invalid

- Clean Shared: A read access to the block will succeed. Unless the block the subblock is a part of is in the Valid Exclusive state, a write to the subblock will force an invalidation transaction on the bus.

- Dirty Shared: The subblock is treated like a Clean Shared sbublock, except that it must be written back on replacement. At most one cache will have a given subblock in either the Dirty Shared or Dirty state.

- Dirty: The subblocks is exclusive to this cache. It must be written back on replacement. Read and write access to this subblock hit with no bus transaction.

Basic idea of this protocol is to do more data transfer between caches and less off-chip memory access.

In contrast with Illinois protocol, on read misses, shared cache block sends cached sublock and also all other clean and dirty shared subblockes in that block.

If the subblock is in the main memory, cache snooper pass the information of caches subblocks and memory will provide the requested subblock along with sublocks which are not currently cached.

On write to clean subblockes and write misses, snooper invalidates only the subblock to be written to avoid the penalties associated with false sharing.

In contrast with Illinois protocol, this protocol requires extra power cycle to maintain the extra state and more logic. <ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

Basic idea of this protocol is to do more data transfer between caches and less off-chip memory access.

In contrast with Illinois protocol, on read misses, shared cache block sends cached sublock and also all other clean and dirty shared subblockes in that block.

If the subblock is in the main memory, cache snooper pass the information of caches subblocks and memory will provide the requested subblock along with sublocks which are not currently cached.

On write to clean subblockes and write misses, snooper invalidates only the subblock to be written to avoid the penalties associated with false sharing.

In contrast with Illinois protocol, this protocol requires extra power cycle to maintain the extra state and more logic. <ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

Subblock protocol

This snoopy-based protocol mitigate the features of Illinois MESI protocol and write policies with subblock validation to take the advantages of both small and large cache block size by using subblock. <ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

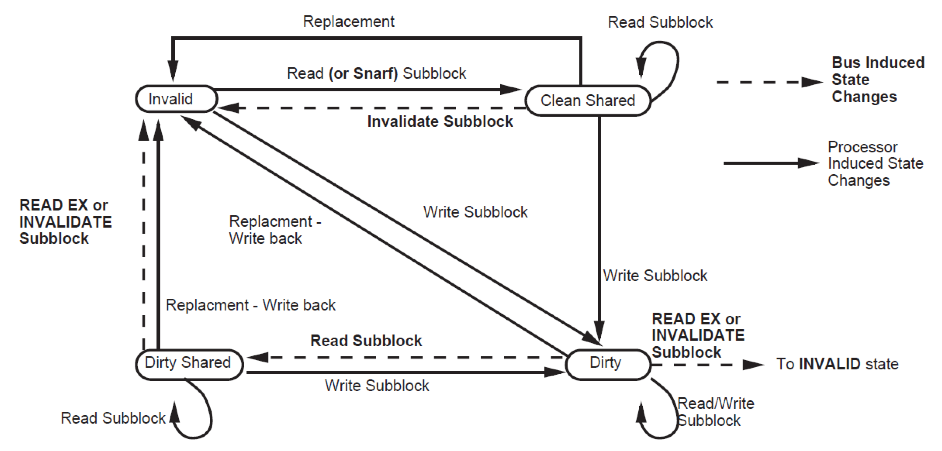

Read-snarfing protocol

This is an enhancement to snoopy-cache coherence protocols that takes advantage of the inherent broadcast nature of the bus.

In contrast with MESI protocol, if one processor wants to reload data in its cache due cache miss, read-snarfing protocol will effectively supply the block to other processors whose blocks were invalidated in the past. Only one read is required to restore the block to all caches which are invalidated.

Protocol modifies the normal updated protocol by updating only those sub-blocks which are modified and update only need to broadcast when the data is actively shared. Read-snarfing protocol maintains a counter and invalidation threshold (Tb) for each cache block “b” to overcome the drawback of WI’s write after read problem. Protocol predicts the number of write operations happens on a single cache block before a read request to the same cache block. Invalidation request is being broadcasted when the write counter reaches the Tb and protocol dynamically adjust the value of Tb based on the nature of program execution.

Simple algorithm of Read-snarfing Random Walk protocol is as follows: Initially Tb of each cache block b is set to 0. <ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

// Number of Write operation happens before being accessed by other processor

If (most recent write run > R) { If(Tb > 1) {

Tb--;

}

} else {

If(R > Tb) {

Tb++;

}

}

R = Invalidation Ratio which is (Ci + Cr) / Cu

Ci: The cost in bus cycles of an invalidation transaction

Cu: The cost in bus cycles of an update transaction

Cr: The cost in bus cycles of reading a cache block

Block will be invalidated immediately with no wasted updates when Threshold reduces to 0. When block is actively shared, block is not invalidated by adjusting the Tb upward. <ref>http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCIQFjAA&url=ftp%3A%2F%2Fftp.cs.washington.edu%2Ftr%2F1994%2F05%2FUW-CSE-94-05-02.PS.Z&ei=2n9kT8gjhPDSAaO2nb4P&usg=AFQjCNFFRgsJiBWjKAMOHcGcRL_vkkSqLg&sig2=aYWddXJdXsNNIFQ5U4zoqg</ref>

-

Example 1

- Suppose invalidation ratio (R) = 5

- Current threshold block (Tb) = 3

- If the processor writes 4 times before it is accessed by other processor, according to the above logic, Tb will be 4.

- This means Tb is at the best possible value and only update can be issues.

Example 2

- Consider, R= 5 and Tb = 3 for a particular block

- If the processor writes 10 times before it is accessed by other processor

- Tb will be 2. (Decreased)

- So the protocol can incur a cost of 2 updates, 1 invalidate and 1 reread.

- After 2 more write, Tb will be 0 and invalidation will occur immediately.

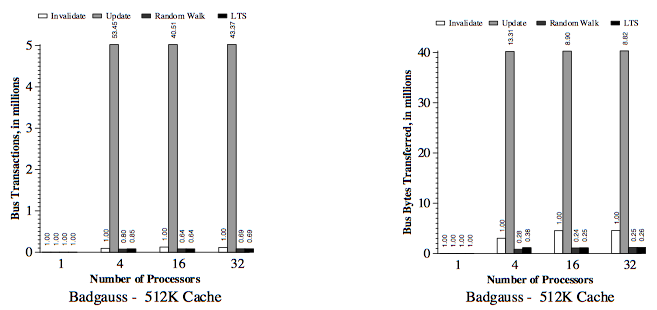

Simulation result

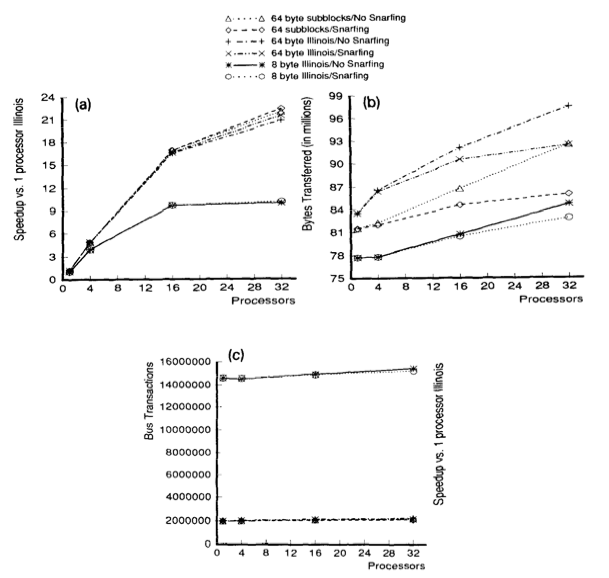

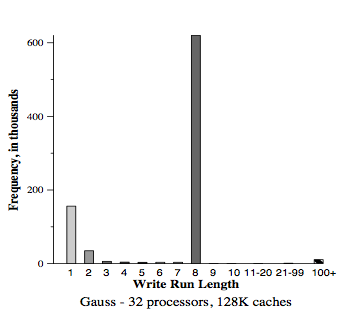

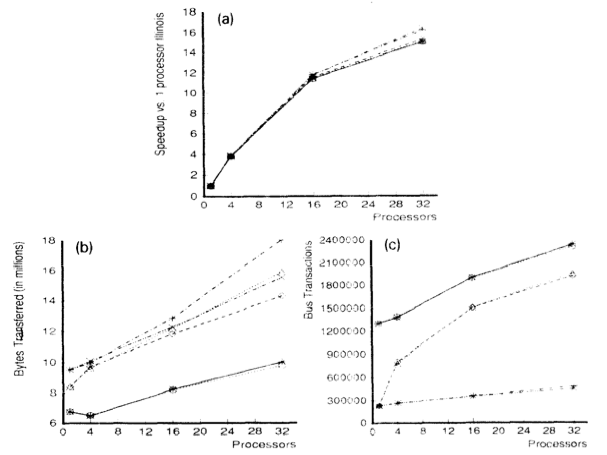

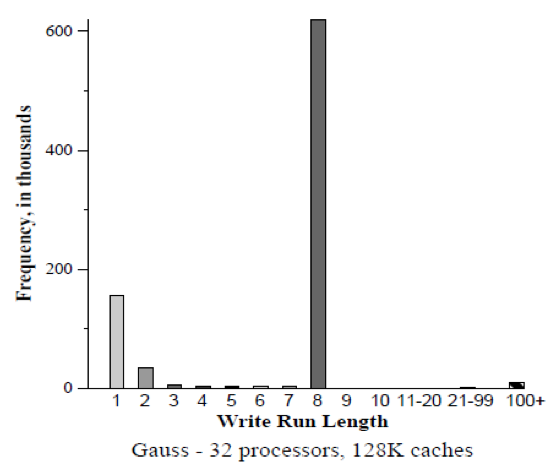

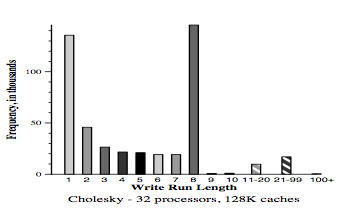

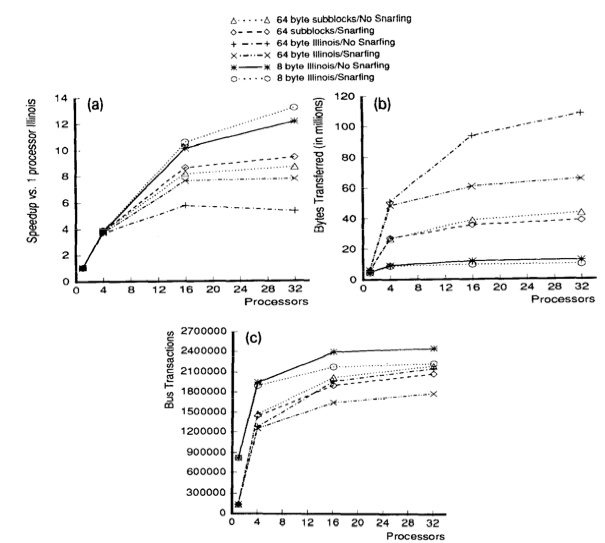

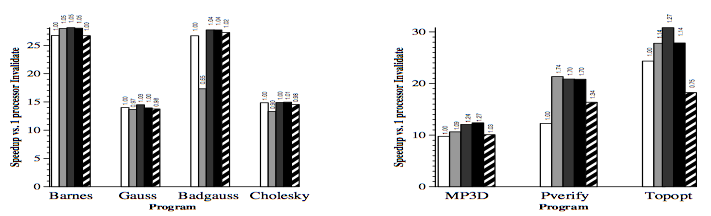

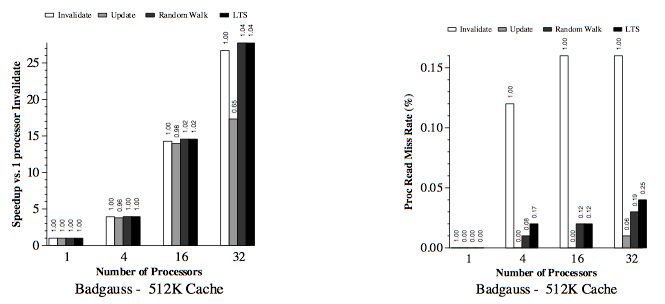

For all simulated results, the considered subblock size (b) was 8 byte and two-way set-associative (K = 2). In order to minimize simulation time, data was only simulated with relatively large caches (C = 128K).

First, below are the results for the two applications (Gauss and Cholesky) that do well using large block sixes. Next, the data results for the three applications (MP3D, Topopt, and Pverify) that performs better using smaller block sixes are listed below. Finally, the report on results running Barnes, for which the choice of block size is not very important. The results of the simulation verified and compared the protocol with both usual and sector caches with 1, 4, 16 and 32 processors where usual cache uses Illinois protocol whereas sector cache uses read-snurfing protocol.

Fig: (a-c) Gauss (128K cache) uses large cache block

Fig: (a-c) Cholesky (128 K cache) application uses large cache block

Fig: (a-c) MP3D (128 K cachees) application which uses smaller block sizes.

Conclusion:

This article used two techniques to improve application performance on bus-based multiprocessor. First technique was using subblock cache coherence protocol by implementing combination of large block and the subset with small cache blocks to take both, the advantages of spatial locality, and avoid false-sharing. The second technique was Read-snarfing in order to reduce the number of read misses caused by previous cache coherence protocol action. The simulation report above showed that subblock protocol works better than MESI protocol for the 64 byte cache block size, but for small block size Illinois protocol works better because subblock protocol uses large transfer block. In addition, Read-snarfing protocol is effective in reducing the amount of data transfer and number of bus transaction which turns out the utilization of lower bus rate and higher application speedups.

<ref>http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.126.3761&rep=rep1&type=pdf</ref>