CSC/ECE 517 Fall 2012/ch2a 2w15 rr

Introduction

Object-oriented design is a programming model that began in the late 60's as software programs became more complex. The idea behind the approach was to build software systems by modeling them based on the real-world objects that they were trying to represent. For example, banking systems would contain customer objects, account objects and so on. Today, object-oriented design has been widely adopted <ref> Introduction to Object Oriented Design</ref>. When done properly, this approach leads to simple, robust, flexible and modular software. When something goes wrong, the results could be bad. Object oriented design can be seen from different perspectives. In the language-centric perspective, objects are containers of data and methods. The model-centric perspective views the objects as model elements reflecting the real world objects and Responsibility-centric perspective views objects as interacting elements each playing a role in object community. Each of these perspectives are outlined in the following sections.

Background

The history of object oriented design has many branches, and many people have contributed to this domain. The 1960s and 1970s saw the emergence of object oriented programming languages, such as Simula and Smalltalk, with key contributors such as Kristen Nygaard and Alan Kay, the visionary computer scientist who founded Smalltalk.<ref>History of Object Oriented Design</ref> But object oriented design was informal through that period, and it was only form 1982 that it became popular. Contributors in this domain include Grady Booch, Kent Beck, Peter Coad, Don Firesmith, Ivar Jacobson (a UML founder), Steve Mellor, Bertrand Meyer, Jim Rumbaugh (a UML founder) and Rebecca Wirfs-Brock among others. Each of these perspectives are outlined in the following sections.

Object Oriented Design Perspectives

Language-centric perspective

The focus of the language-centric perspective is classes and objects as building blocks for developing software. The emphasis is on the internal structure which are the fields and methods. Thus it is inherently a compile-time or static view which means that the definition speaks in terms of what it looks like in the following code:

public class foo

{

private int x;

public static double y;

public int double (int x)

{

return (3*x);

}

}

The implicit aspect of this view is that, an object is an entity in its own right and the definition is closed. Any object can be understood in isolation where the fields and methods are just enumerated. The advantage of this perspective is of that it is very concrete, closely related to the programming language level and therefore it is easy to understand. The disadvantage is that it does not help to structure the collaboration between objects, the dynamics, and this is typically where the hard challenges of design lie. Thus the perspective offers little guidance in the process of designing any realistic system.<ref>Henrik Baerbak Christensen, "Implications of Perspective in Teaching Objects First and Object Design", Proceedings of the 10th annual SIGCSE conference on Innovation and technology in computer science education, Department of Computer Science, University of Aarhus, 2005.</ref>

Model-centric perspective

In this perspective, the objects(classes, fields) and their relationships like inheritance, association, aggregation are designed by using some model. Here the program execution is a simulation of some part of the world, and objects are perceived as the parts of the model. The perspective is often explained through analogies to other models like toy railways, traffic simulations, computer games, etc. This perspective stresses objects as entities in a larger context (they are parts of a model) as opposed to the self-contained language-centric definition. This approach works fine for real life systems such as an order-entry system, a library system, boat-rental and various other real world entity oriented systems. This naturally leads to a strong focus on what the relations are between the parts: association, generalization, composition. Dynamics is an inherent part of the concept simulation and the explicit guideline for designing object interaction is to imitate real world or model interactions. Let us consider a real world example of designing a partial implementation of the board game-Backgammon to understand the objected oriented using a model-centric perspective. The physical parts of Backgammon identifiable are the checkers, points, board, dice, player, etc. The diagram below is a design of model parts (classes) and their relationships (relations).

Responsibility-centric perspective

This perspective stresses on the behavior of software systems and the concepts used to do design include behavior, roles, responsibilities and protocol. Here, the primary focus is the dynamics of the program. Roles and responsibilities are the core concepts in this perspective and hence it has more coupling to behavior when compared to static elements like objects or model parts. There is a difference between behavior and responsibility, where behavior is the concrete actions taken by objects where as responsibility is to fulfill requests through any number of concrete behaviors. So, responsibility is more abstract than behavior. One can look at responsibility-centric perspective as an extension of the model-centric perspective with a shift of focus (from a focus on model parts to a focus on the simulation or dynamical aspects). The Backgammon example can again be

Object Oriented Design Concepts <ref>http://books.google.com/books/about/Object_Design.html?id=vUF72vN5MY8C</ref>

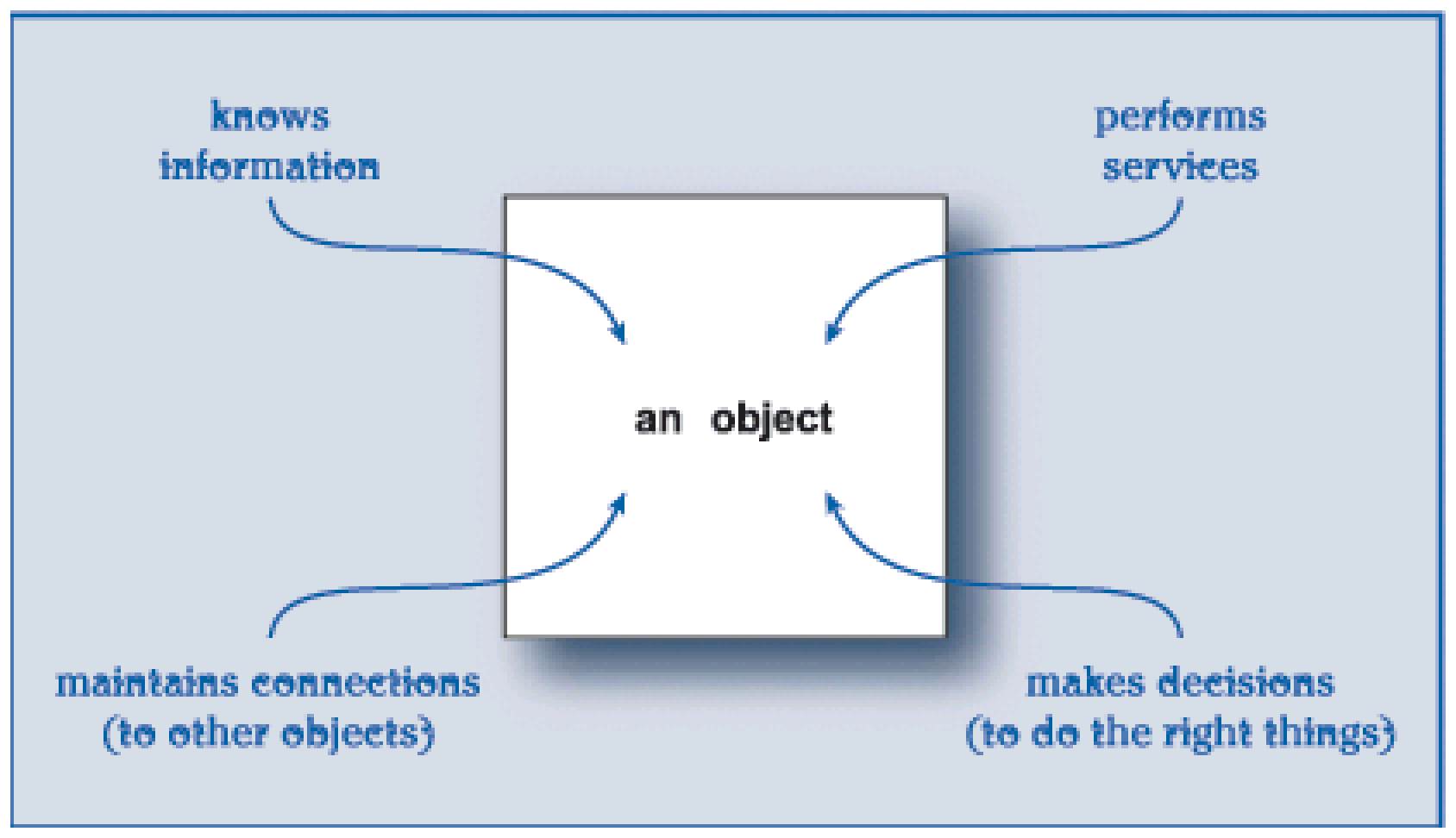

A software application is constructed from parts. These parts -software objects- interact by sending messages to request information or action from others. Throughout its lifetime, each object remains responsible for responding to a fixed set of requests. To fulfill these requests, objects encapsulate scripted responses and the information that they base them on (see Figure 4a). If an object is designed to remember certain facts, it can use them to respond differently to future requests.

Building an object-oriented application means inventing appropriate machinery. We represent real-world information, processes, interactions, relationships, even errors, by inventing objects that don't exist in the real world. We give life and intelligence to inanimate things. We take difficult-to-comprehend real-world objects and split them into simpler, more manageable software ones. We invent new objects. Each has a specific role to play in the application. Our measure of success lies in how clearly we invent a software reality that satisfies our application's requirements—and not in how closely it resembles the real world.

For example, filling out and filing a form seems simple. But to perform that task in software, behind the simple forms, the application is validating the data against business rules, reading and refreshing the persistent data, guaranteeing the consistency of the information, and managing simultaneous access by dozens of users. Software objects display information, coordinate activities, compute, or connect to services.

An object = an implementation of one or more roles A role = a set of related responsibilities A responsibility = an obligation to perform a task or know information

| Concept | Short description |

|---|---|

| An object | an implementation of one or more roles. |

| A role | a set of related responsibilities. |

| A responsibility | an obligation to perform a task or know information |

Behavior

Responsibilities

Roles

A role is a set of responsibilities that can be used interchangeably.

Protocols

References

<references />