CSC/ECE 517 Fall 2012/ch2b 2w42 aa: Difference between revisions

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

This mechanism makes exchanging product families easy because the specific class of the factory object appears only once in the application - where it is instantiated. The application can wholesale replace the entire family of products simply by instantiating a different concrete instance of the abstract factory. Because the service provided by the factory object is so pervasive, it is routinely implemented as a Singleton.<br> | This mechanism makes exchanging product families easy because the specific class of the factory object appears only once in the application - where it is instantiated. The application can wholesale replace the entire family of products simply by instantiating a different concrete instance of the abstract factory. Because the service provided by the factory object is so pervasive, it is routinely implemented as a Singleton.<br> | ||

== Abstract Factory Example == | == Abstract Factory Example == | ||

Revision as of 00:54, 20 November 2012

Introduction

Facade Pattern

Intent

- Provide a unified interface to a set of interfaces in a subsystem.

- Wrap a complicated subsystem with a simpler interface.

Facade discusses encapsulating a complex subsystem within a single interface object. This reduces the learning curve necessary to successfully leverage the subsystem. It also promotes decoupling the subsystem from its potentially many clients. On the other hand, if the Facade is the only access point for the subsystem, it will limit the features and flexibility that “power users” may need. The Facade object should be a fairly simple advocate or facilitator. It should not become an all-knowing oracle or “god” object.

Adapter Pattern

Intent

- Convert the interface of a class into another interface clients expect. Adapter lets classes work together that couldn’t otherwise because of incompatible interfaces.

- Wrap an existing class with a new interface.

- Impedance match an old component to a new system.

Convert the interface of a class into another interface clients expect. Adapter lets classes worktogether that couldn't otherwise because of incompatible interfaces.

Abstract Factory Pattern

Intent

- Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.

- A hierarchy that encapsulates: many possible “platforms”, and the construction of a suite of “products”.

- The new operator considered harmful.

If an application is to be portable, it needs to encapsulate platform dependencies. These “platforms” might include: windowing system, operating system, database, etc. Too often, this encapsulatation is not engineered in advance, and lots of #ifdef case statements with options for all currently supported platforms begin to procreate like rabbits throughout the code.

Mediator Pattern

Intent

- Define an object that encapsulates how a set of objects interact. Mediator promotes loose coupling by keeping objects from referring to each other explicitly, and it lets you vary their interaction independently.

- Design an intermediary to decouple many peers.

- Promote the many-to-many relationships between interacting peers to “full object status”.

Facade Pattern

Non-Software examples

In most of the Pizza centers, orders will be given through phone calls with the customer interacting with the Customer service representative. In this case, consumers do not have access to the Billing system, Kitchen and delivery department. The customer service representative acts as an interface and interacts with each of the departments involved in the transaction and ensures that Pizzas are delivered to the consumer. Customer Service representative corresponds to the facade. Individual departments involved in the transaction correspond to Sub-systems.

Software examples

Web Service Facade Solution Architecture provides an example for Facade design pattern. In this architectural solution, instead of rewriting legacy applications or customizing those with middleware to connect to other applications one by one, this solution helps create a "facade" for the legacy application. Other applications are easily "plugged into" this facade. By modeling a legacy application into its basic functions of create, read, update, and delete and then exposing these functions as Web methods, the Web service facade solution allows other applications to access legacy data by making use of common Web services through standardized protocols. In this way, Facade decouples layers so that they do not depend on each other which can make it easier to develop, to use and to promote code re-use.

C# Example

using System; using System.Collections.Generic;

namespace DesignPatterns.Facade { public class OrderFacade { //Places an Order and Returns an Order ID public int placeOrder(int CustomerID, List<BasketItem> Products) { Order anOrder = new Order(); OrderLine anOrderLine = new OrderLine(); Address DespatchAddress = Address.getCustomerDespatchAddress(CustomerID); int OrderId = anOrder.requestOrderID(); anOrder.createOrder(OrderId, DespatchAddress); anOrderLine.addOrderLinesToOrder(OrderId, Products); return OrderId; } }

//order class public class Order { public int requestOrderID() { //Creates and Returns a Unique Order ID }

public void createOrder(int OrderId, Address DespatchAddress) { } }

//OrderLine Class public class OrderLine { public void addOrderLinesToOrder(int OrderId, List<BasketItem> Products) { } }

//Public Customer public class Address { public static Address getCustomerDespatchAddress(int CustomerID) { return new Address(); } //Address properties }

public class BasketItem { //BasketItem Properties } }

Adapter Pattern and Facade Pattern

Adapter functions as a wrapper or modifier of an existing class. It provides a different or translated view of that class. An “off the shelf” component offers compelling functionality that you would like to reuse, but its “view of the world” is not compatible with the philosophy and architecture of the system currently being developed. Reuse has always been painful and elusive. One reason has been the tribulation of designing something new, while reusing something old. There is always something not quite right between the old and the new. It may be physical dimensions or misalignment. It may be timing or synchronization. It may be unfortunate assumptions or competing standards. It is like the problem of inserting a new three-prong electrical plug in an old two-prong wall outlet – some kind of adapter or intermediary is necessary.

Adapter is about creating an intermediary abstraction that translates, or maps, the old component to the new system. Clients call methods on the Adapter object which redirects them into calls to the legacy component. This strategy can be implemented either with inheritance or with aggregation.

Adapter Pattern Example

interface Shape {

void draw(...);

}

Class LegacyLine {

void draw(..) { }

}

Class LegacyRectangle {

void draw(..) { }

}

Class Line implements Shape {

adapter = new LegacyLine();

void draw(...) {adapter.draw(...)}

}

Class Rectangle implements Shape {

adapter = new LegacyRectangle();

void draw(...) {adapter.draw(...)}

}

In the example provided for the Facade pattern, the method placeOrder() uses the methods exposed by many other classes such as Order, OrderLine, Address etc to provide a high level view for the callers. The callers need not worry about the complexities in handling the sub-system. The users of the Class OrderFacade just invoke the method placeOrder() with the necessary arguments and rest of the process is taken care by placeOrder(). As can be seen in this case, a new method (placeOrder) was defined which has the logic and the necessary steps to handle all the sub-systems to create an order, create an id for the order, create a dispatch address etc.

In the example provided for the Adapter pattern, no new methods are defined. The existing method draw of LegacyRectangle is wrapped in a adapter class Rectangle. The methods in adapter classes does the necessary manipulations to the arguments and then passes to the original classes.

On similar lines, assume that the implementation and structure of BasketItem in Facade example needs to be changed. To handle such scenario, a new adapter class BasketItemAdapter is defined. It implements all the methods of the BasketItem and in each method makes necessary changes to the arguments and passes it to the new implementation as shown below.

Example

public Class BasketItemAdapter {

BasketItem newImplementation = new BasketItem();

void calculateCost(...) {

//make necessary modification

newImplementation.calculateCost(...);

}

}

Differences and similarities

- In both the Facade and Adapter pattern we have pre-existing classes.

- In the Facade, however, we do not have an interface we must design to, as we do in the Adapter pattern.

- We are not interested in polymorphic behavior in the Facade, while in the Adapter, We probably am.(There are times when we just need to design to a particular API and therefore must use an Adapter)

- In the case of the Facade pattern, the motivation is to simplify the interface. With the Adapter, while simpler is better,We are trying to design to an existing interface and cannot simplify things even if a simpler interface were otherwise possible.

Bottom line is a Facade simplifies an interface while an Adapter converts the interface into a pre-existing interface.

Abstract Factory Pattern and Facade Pattern

Abstract factory pattern provides a level of indirection that abstracts the creation of families of related or dependent objects without directly specifying their concrete classes. The “factory” object has the responsibility for providing creation services for the entire platform family. Clients never create platform objects directly, they ask the factory to do that for them.

This mechanism makes exchanging product families easy because the specific class of the factory object appears only once in the application - where it is instantiated. The application can wholesale replace the entire family of products simply by instantiating a different concrete instance of the abstract factory. Because the service provided by the factory object is so pervasive, it is routinely implemented as a Singleton.

Abstract Factory Example

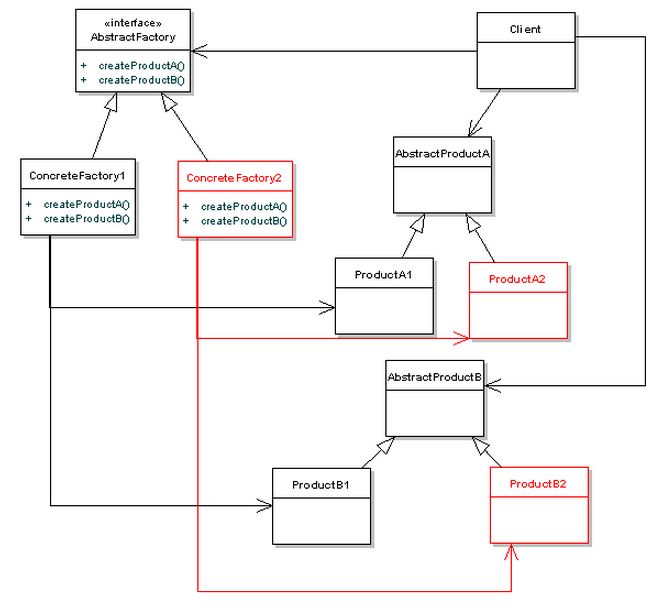

The AbstractFactory defines the interface that all of the concrete factories will need to implement in order to product Products. ConcreteFactoryA and ConcreteFactoryB have both implemented this interface here, creating two seperate families of product. Meanwhile, AbstractProductA and AbstractProductB are interfaces for the different types of product. Each factory will create one of each of these AbstractProducts.

The Client deals with AbstractFactory, AbstractProductA and AbstractProductB. It doesn't know anything about the implementations. The actual implementation of AbstractFactory that the Client uses is determined at runtime.

As you can see, one of the main benefits of this pattern is that the client is totally decoupled from the concrete products. Also, new product families can be easily added into the system, by just adding in a new type of ConcreteFactory that implements AbstractFactory, and creating the specific Product implementations.

Facade Pattern Example

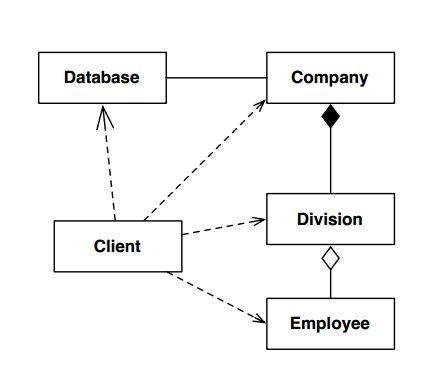

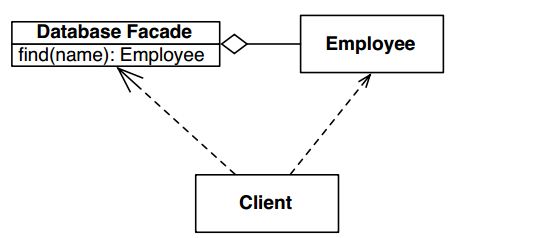

Considering the example for the Facade pattern, Client requires access to Employee objects, but in order to get that, it first need to contact the Database and retrieve the Company objects. It then retrieves Division objects from them and finally gains access to Employee objects. So, we see that It uses four classes and has to deal with complex details of the sub system. With Facade, the Client is shielded from most of the classes. It uses the Database Facade to retrieve Employee objects directly.

Differences and similarities between Facade and Abstract Factory patterns

- Facade is a structural design pattern whereas Abstract Factory pattern is a creational design pattern.

- Both are similar in a way that both provide an interface. Abstract Factory , provides kind of a Facade for creating products that belongs to its own factories.

- With the Abstract Factory Pattern we just provide a common factory builder for many different builders for the same thing. This can be used whenever we need to provide an interface to a set of builders meant to be used with something in common (the product) without bothering on what are we going to build or which factory are we going to use. The Facade pattern instead is used to provide a simple interface to a lot of different operations that the client classes should not see.

Thus we see that both patterns achieve quite different goals. The facade pattern is used when you want to hide an implementation or it is about changing interface of some class or set of classes. On the other hand Abstarct factory pattern is used when you want to hide the details on constructing instances. Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.

Mediator Pattern and Facade Pattern

In Unix, permission to access system resources is managed at three levels of granularity: world, group, and owner. A group is a collection of users intended to model some functional affiliation. Each user on the system can be a member of one or more groups, and each group can have zero or more users assigned to it. Next figure shows three users that are assigned to all three groups. If we were to model this in software, we could decide to have User objects coupled to Group objects, and Group objects coupled to User objects. Then when changes occur, both classes and all their instances would be affected. An alternate approach would be to introduce “an additional level of indirection” - take the mapping of users to groups and groups to users, and make it an abstraction unto itself. This offers several advantages: Users and Groups are decoupled from one another, many mappings can easily be maintained and manipulated simultaneously, and the mapping abstraction can be extended in the future by defining derived classes.

Partitioning a system into many objects generally enhances reusability, but proliferating interconnections between those objects tend to reduce it again. The mediator object: encapsulates all interconnections, acts as the hub of communication, is responsible for controlling and coordinating the interactions of its clients, and promotes loose coupling by keeping objects from referring to each other explicitly.

Colleagues (or peers) are not coupled to one another. Each talks to the Mediator, which in turn knows and conducts the orchestration of the others. The “many to many” mapping between colleagues that would otherwise exist, has been “promoted to full object status”. This new abstraction provides a locus of indirection where additional leverage can be hosted.

Mediator is similar to Facade in that it abstracts functionality of existing classes. Mediator abstracts/centralizes arbitrary communication between colleague objects, it routinely “adds value”, and it is known/referenced by the colleague objects (i.e. it defines a multidirectional protocol). In contrast, Facade defines a simpler interface to a subsystem, it doesn’t add new functionality, and it is not known by the subsystem classes (i.e. it defines a unidirectional protocol where it makes requests of the subsystem classes but not vice versa).