CSC/ECE 517 Fall 2012/ch2a 2w15 rr: Difference between revisions

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

world, and objects are perceived as the parts of the model. The perspective is often explained through analogies to other models like toy railways, traffic simulations, computer games, etc. This perspective stresses objects as entities in a larger context (they are parts of a model) as opposed to the self-contained language-centric definition. This approach works fine for real life systems such as an order-entry system, a library system, boat-rental and various other real world entity oriented systems. This naturally leads to a strong focus on what the relations are between the parts: association, generalization, composition. Dynamics is an inherent part of the concept simulation and the explicit guideline for designing object interaction is to imitate real world or model interactions. | world, and objects are perceived as the parts of the model. The perspective is often explained through analogies to other models like toy railways, traffic simulations, computer games, etc. This perspective stresses objects as entities in a larger context (they are parts of a model) as opposed to the self-contained language-centric definition. This approach works fine for real life systems such as an order-entry system, a library system, boat-rental and various other real world entity oriented systems. This naturally leads to a strong focus on what the relations are between the parts: association, generalization, composition. Dynamics is an inherent part of the concept simulation and the explicit guideline for designing object interaction is to imitate real world or model interactions. | ||

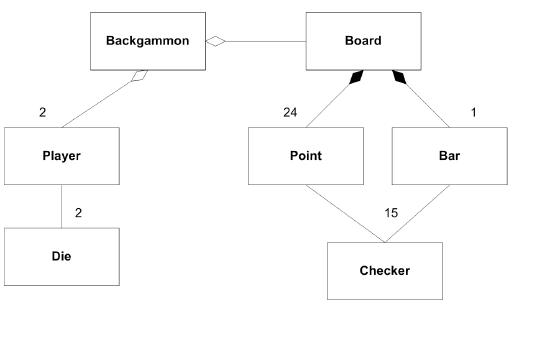

Let us consider a real world example of designing a partial implementation of the board game-Backgammon to understand the objected oriented using a model-centric perspective. The physical parts of Backgammon identifiable are the checkers, points, board, dice, player, etc. The diagram below is a design of model parts (classes) and their relationships (relations). | Let us consider a real world example of designing a partial implementation of the board game-Backgammon to understand the objected oriented using a model-centric perspective. The physical parts of Backgammon identifiable are the checkers, points, board, dice, player, etc. The diagram below is a design of model parts (classes) and their relationships (relations). | ||

[[File:ood.jpg]] | [[File:ood.jpg]] | ||

===Responsibility-centric perspective=== | ===Responsibility-centric perspective=== | ||

Revision as of 20:41, 23 October 2012

Introduction

Object-oriented design is a programming model that began in the late 60's as software programs became more complex. The idea behind the approach was to build software systems by modeling them based on the real-world objects that they were trying to represent. For example, banking systems would contain customer objects, account objects and so on. Today, object-oriented design has been widely adopted <ref> Introduction to Object Oriented Design</ref>. When done properly, this approach leads to simple, robust, flexible and modular software. When something goes wrong, the results could be bad. Object oriented design can be seen from different perspectives. In the language-centric perspective, objects are containers of data and methods. The model-centric perspective views the objects as model elements reflecting the real world objects and Responsibility-centric perspective views objects as interacting elements each playing a role in object community. Each of these perspectives are outlined in the following sections.

Background

The history of object oriented design has many branches, and many people have contributed to this domain. The 1960s and 1970s saw the emergence of object oriented programming languages, such as Simula and Smalltalk, with key contributors such as Kristen Nygaard and Alan Kay, the visionary computer scientist who founded Smalltalk.<ref>History of Object Oriented Design</ref> But object oriented design was informal through that period, and it was only form 1982 that it became popular. Contributors in this domain include Grady Booch, Kent Beck, Peter Coad, Don Firesmith, Ivar Jacobson (a UML founder), Steve Mellor, Bertrand Meyer, Jim Rumbaugh (a UML founder) and Rebecca Wirfs-Brock among others. Each of these perspectives are outlined in the following sections.

Object Oriented Design Perspectives

Language-centric perspective

The focus of the language-centric perspective is classes and objects as building blocks for developing software. The emphasis is on the internal structure which are the fields and methods. Thus it is inherently a compile-time or static view which means that the definition speaks in terms of what it looks like in the following code:

public class foo

{

private int x;

public static double y;

public int double (int x)

{

return (3*x);

}

}

The implicit aspect of this view is that, an object is an entity in its own right and the definition is closed. Any object can be understood in isolation where the fields and methods are just enumerated. The advantage of this perspective is of that it is very concrete, closely related to the programming language level and therefore it is easy to understand. The disadvantage is that it does not help to structure the collaboration between objects, the dynamics, and this is typically where the hard challenges of design lie. Thus the perspective offers little guidance in the process of designing any realistic system.<ref>Henrik Baerbak Christensen, "Implications of Perspective in Teaching Objects First and Object Design", Proceedings of the 10th annual SIGCSE conference on Innovation and technology in computer science education, Department of Computer Science, University of Aarhus, 2005.</ref>

Model-centric perspective

In this perspective, the objects(classes, fields) and their relationships like inheritance, association, aggregation are designed by using some model. Here the program execution is a simulation of some part of the world, and objects are perceived as the parts of the model. The perspective is often explained through analogies to other models like toy railways, traffic simulations, computer games, etc. This perspective stresses objects as entities in a larger context (they are parts of a model) as opposed to the self-contained language-centric definition. This approach works fine for real life systems such as an order-entry system, a library system, boat-rental and various other real world entity oriented systems. This naturally leads to a strong focus on what the relations are between the parts: association, generalization, composition. Dynamics is an inherent part of the concept simulation and the explicit guideline for designing object interaction is to imitate real world or model interactions. Let us consider a real world example of designing a partial implementation of the board game-Backgammon to understand the objected oriented using a model-centric perspective. The physical parts of Backgammon identifiable are the checkers, points, board, dice, player, etc. The diagram below is a design of model parts (classes) and their relationships (relations).

Responsibility-centric perspective

This perspective stresses on the behavior of software systems and the concepts used to do design include behavior, roles, responsibilities and protocol. Here, the primary focus is the dynamics of the program. Roles and responsibilities are the core concepts in this perspective and hence it has more coupling to behavior when compared to static elements like objects or model parts. There is a difference between behavior and responsibility, where behavior is the concrete actions taken by objects where as responsibility is to fulfill requests through any number of concrete behaviors. So, responsibility is more abstract than behavior. One can look at responsibility-centric perspective as an extension of the model-centric perspective with a shift of focus (from a focus on model parts to a focus on the simulation or dynamical aspects). The Backgammon example can again be

Object Oriented Design Concepts <ref>http://books.google.com/books/about/Object_Design.html?id=vUF72vN5MY8C</ref>

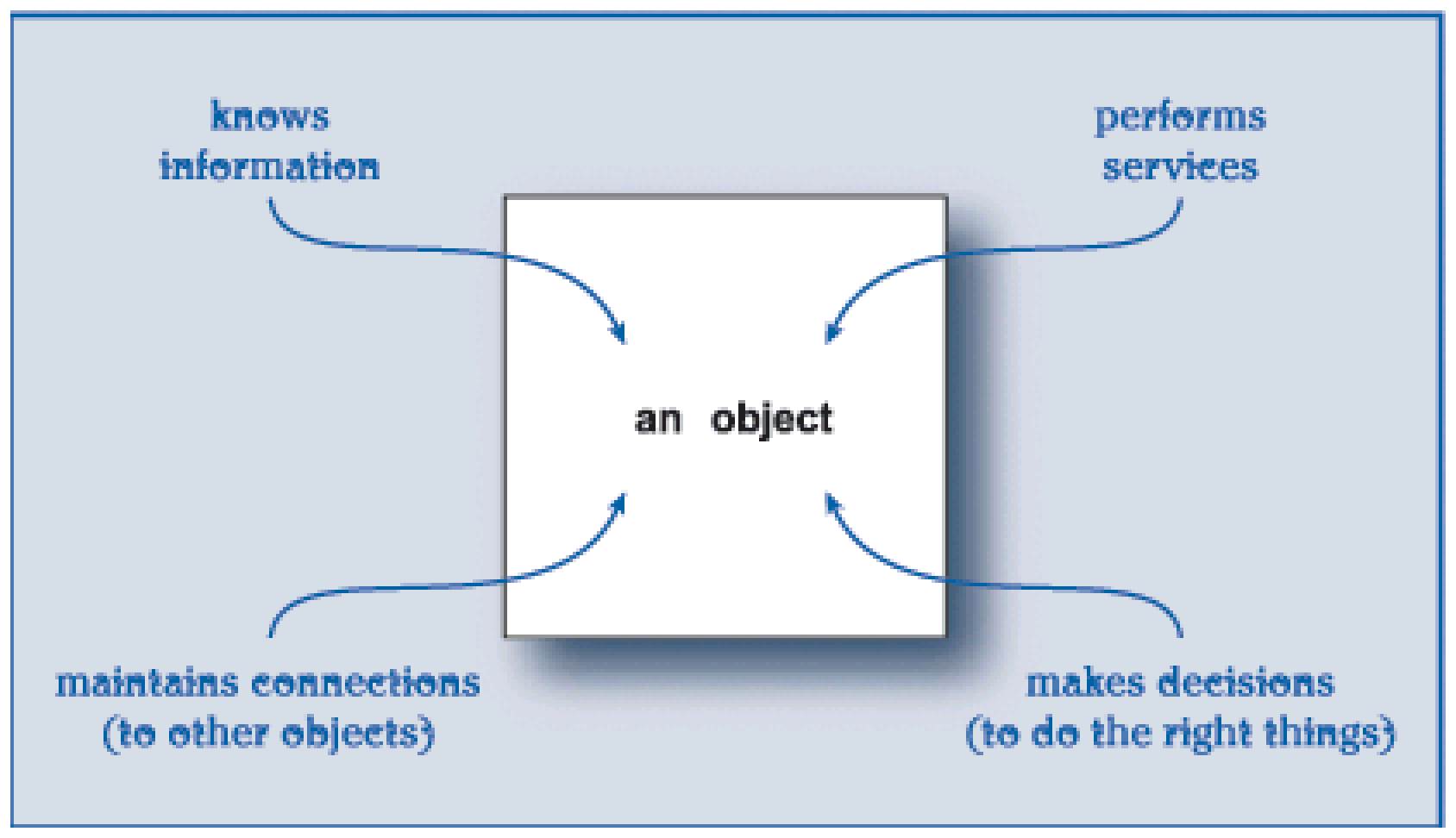

A software application is constructed from parts. These parts -software objects- interact by sending messages to request information or action from others. Throughout its lifetime, each object remains responsible for responding to a fixed set of requests. To fulfill these requests, objects encapsulate scripted responses and the information that they base them on (see Figure 4a). If an object is designed to remember certain facts, it can use them to respond differently to future requests.

Building an object-oriented application means inventing appropriate machinery. We represent real-world information, processes, interactions, relationships, even errors, by inventing objects that don't exist in the real world. We give life and intelligence to inanimate things. We take difficult-to-comprehend real-world objects and split them into simpler, more manageable software ones. We invent new objects. Each has a specific role to play in the application. Our measure of success lies in how clearly we invent a software reality that satisfies our application's requirements—and not in how closely it resembles the real world.<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=vUF72vN5MY8C&pg=PA3&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=4#v=onepage&q&f=false Object Design: Roles, Responsibilities, and Collaborations by Rebecca Wirfs-Brock, Alan McKean</ref>

For example, filling out and filing a form seems simple. But to perform that task in software, behind the simple forms, the application is validating the data against business rules, reading and refreshing the persistent data, guaranteeing the consistency of the information, and managing simultaneous access by dozens of users. Software objects display information, coordinate activities, compute, or connect to services.

| Concept | Short description |

|---|---|

| An object | an implementation of one or more roles. |

| A role | a set of related responsibilities. |

| A responsibility | an obligation to perform a task or know information |

Roles (relation with objects)

An object has a specific purpose - a role it plays within a given context. Objects that play the same role can be interchanged. For example, there are several providers that can deliver letters and packages: DHL, FedEx, UPS, Post, Airborne. They all have the same purpose, if not the same way of carrying out their business. We choose from among them according to the requirements that you have for delivery. We pick among the mail carriers that meet your requirements.

A role is a set of responsibilities that can be used interchangeably.

A well-defined object supports a clearly defined role. We use purposeful oversimplifications, or role stereotypes, to help focus an object's responsibilities. Stereotypes are characterizations of the roles needed by an application. Because our goal is to build consistent and easy-to-use objects, it is advantageous to stereotype objects, ignoring specifics of their behaviors and thinking about them at a higher level. By oversimplifying and characterizing it, we can ponder the nature of an object's role more easily. We find these stereotypes to be useful:

- Information holder - knows and provides information

- Structurer - maintains relationships between objects and information about those relationships

- Service provider - performs work and, in general, offers computing services

- Coordinator - reacts to events by delegating tasks to others

- Controller - makes decisions and closely directs others' actions

- Interfacer - transforms information and requests between distinct parts of our system

Just as an actor tries to play a believable part in a play, an object takes on a character in an application by assuming responsibilities that define a meaningful role.

Responsibilities <ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=vUF72vN5MY8C&pg=PA5&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=4#v=onepage&q&f=false</ref>

An application implements a system of responsibilities. Responsibilities are assigned to roles. Roles collaborate to carry out their responsibilities. A good application is structured to effectively fulfill these responsibilities. We start design by inventing objects, assigning responsibilities to them for knowing information and doing the application's work. Collectively, these objects work together to fulfill the larger responsibilities of the application.

An object embodies a set of roles with a designated set of responsibilities.

Responsibilities are general statements about software objects. They include three major items:

- The actions an object performs

- The knowledge an object maintains

- Major decisions an object makes that affect others

Physical objects, unlike our intelligent software objects, typically do work or hold on to things or information. A phone book is a physical object but it takes no action. A thermostat exists, and it makes decisions and sends control signals. A teakettle exists, but it does little more than act as a reservoir (and occasionally whistles to send a signal). Physical objects usually don't make informed decisions. However, a dog is man's best friend and companion and does many different things on its own behalf. Our software objects lie somewhere between these extremes: They aren't sentient beings, but they can be more or less lively, depending on what responsibilities we give them.

Responsibilities come from statements or implications of system behavior found in use cases. There is a gap between use case descriptions and object responsibilities. Responsibilities are general statements about what an object knows, does, or decides. Use case descriptions are statements about our system's behavior and how actors interact with it. Use cases describe our software from the perspective of an outside observer. They don't tell how something is accomplished. Use cases provide a rough idea of how our system will work and the tasks involved. As designers we bridge this gap by transforming descriptions found in use cases into explicit statements about actions, information, or decision-making responsibilities. This is a three-step process:

- Identify things the system does and information it manages.

- Restate these as responsibilities.

- Break them down into smaller parts if necessary, and assign them to appropriate objects.

Behavior <ref>http://csis.pace.edu/~bergin/patterns/design.html</ref>

Behavior means activity. It also means having information that other objects may need. In this case the behavior is providing that information. In Mancala, the players play the game, for example. A pit might "know" how many pebbles it contains and it might be asked by another object like a player how many it holds.

"Taking turn" is the behavior a player in 2 player games.

Protocols <ref>http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protocol_(object-oriented_programming)</ref>

In object-oriented programming, a protocol or interface is a common means for unrelated objects to communicate with each other. When objects do collaborate, they are designed to follow certain protocols and observe specific conventions: Make requests only for advertised services. Provide appropriate information. Use services under certain conditions. Finally, accept the consequences of using them. Object contracts should describe all these terms.

The protocol is a description of:

- The messages that are understood by the object.

- The arguments that these messages may be supplied with.

- The types of results that these messages return.

- The invariants that are preserved despite modifications to the state of an object.

- The exceptional situations that will be required to be handled by clients to the object.

Conclusion

In this article we have discussed different object-oriented design perspectives, such as, language-centric, model-centric and responsibility-centric. We have also described the concepts of behavior, responsibilities, roles and protocols. The highlight of the second part is the relation between role and object.

References

<references />