CSC/ECE 506 Spring 2010/chapter 10: Difference between revisions

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

[[Image:TSO1.jpg]] <br /> | [[Image:TSO1.jpg]] <br /> | ||

For TSO, a safety net for write atomicity is required only for a write that is followed by a read to the same location in the same processor. The atomicity can be achieved by ensuring program order from the write to the read using read-modify-writes. | For TSO, a safety net for write atomicity is required only for a write that is followed by a read to the same location in the same processor. The atomicity can be achieved by ensuring program order from the write to the read using read-modify-writes. | ||

<br /> | |||

'''Difference between | '''Difference between IBM370 and TSO:''' <br /> | ||

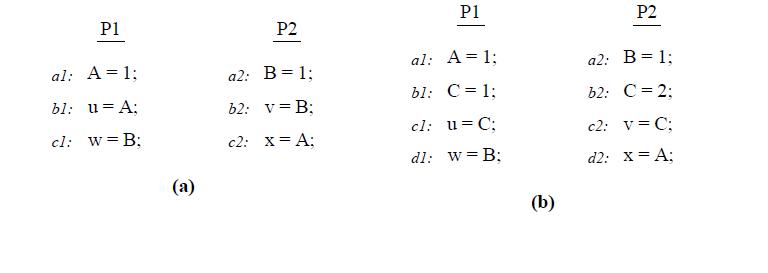

Let us consider the program segment below, taken from reference link http://infolab.stanford.edu/pub/cstr/reports/csl/tr/95/685/CSL-TR-95-685.pdf, to demonstrate the difference between TSO and IBM 370 models. | Let us consider the program segment below, taken from reference link http://infolab.stanford.edu/pub/cstr/reports/csl/tr/95/685/CSL-TR-95-685.pdf, to demonstrate the difference between TSO and IBM 370 models. | ||

Revision as of 18:51, 13 April 2010

Memory Consistency models

Introduction

The memory consistency model of a shared-memory multiprocessor provides a formal specification of how the memory system will appear to the programmer, eliminating the gap between the behavior expected by the programmer and the actual behavior supported by a system. Effectively, the consistency model places restrictions on the values that can be returned by a read in a shared-memory program execution.

This material gives a brief explanation about the intuition behind using relaxed memory consistency models for scalable design of multiprocessors. It also explains about the consistency models in real multiprocessor systems like Digital Alpha, Sparc V9 RMO, IBM Power PC, Intel Pentium, and processors from Sun Microsystems.

Sequential Consistency Model (SC)

To write correct and efficient shared memory programs, programmers need a precise notion of shared memory semantics. To ensure correct execution a programmer expects that the data value read should be the same as the latest value written to it in the system. However in many commercial shared memory systems,the processor may observe an older value, causing unexpected behavior.The Memory consistency model of a shared memory multiprocessor formaly specifies how the memory system will appera to the programmer.Essentially, a memory consistency model restricts the values that a read can return. Intuitively, a read should return the value of the "last" write to the same memory location. In uniprocessors, "last" is precisely defined by the sequential order specified by the program called program order. This is not the case in multiprocessors.A write and read of a variable, Data, are not related by program order because they reside on two different processors.

The uniprocessors model, however can be extented to apply to multiprocessors in a natural way. The resulting model is called Sequential consistency. In brief, sequential consistency requires that all memory operations

- appear to execute one at a time,

- all memory operations of a single processor appear to execute in the order described by that processor's program.

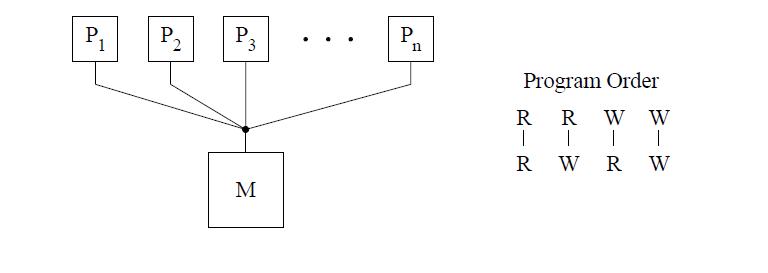

The figure above shows the basic representation for sequential consistency. This conceptual system for SC consists of n processors sharing a single logical memory. Though the figure does not show caches, an SC implementation may still cache data as long as the memory system appears as a single copy memory(i.e the writes should appear atomic). As SC requires program order to be maintained among all operation types, the pictorial representation of the program order shows all combinations of reads and writes, the line between them telling that the operations are required to complete in program order.

This model ensures that the reads of a variable, Data, will return the new values written to it by a processor. Sequential consistency provides a simple, intuitive programming model. Because of its strict consistency requirements,sequential consistency, many of the architecture and compiler optimizations used in uniprocessors are not safely applicable to sequentially consistent multiprocessors.[ For more deatils on sequential consistency model and its advantages/disadvantages refer to solihin textbook pg 284 through 292]. For this reason, many Relaxed consistency models have been proposed, most of which

are supported by commercial architectures.

Performance of Sequential Consistency on multiprocessors

Sequential Consistency (SC) is the most intuitive programming interface for shared memory multiprocessors. A system implementing SC appears to execute memory operations one at a time and in program order. A program written for an SC system requires and relies on a specified memory behavior to execute correctly. Implementing memory accesses according to the SC model constraints, however, would adversely impact performance because memory accesses in shared-memory multiprocessors often incur prohibitively long latencies (tens of times longer than in uniprocessor systems). To enforce sequential consistency, illegal reordering caused by hardware optimizations like Write buffers, Non-blocking caches etc and compiler optimizations like code motion, register allocation,eliminating common subexpressions, loop transformations etc resulting in reordering are not allowed. These are the optimizations which are implemented for better performance and are valid in uniprocessors. But in case of multiprocessors, these do not allow to satisfy the sequential consistency requirements and hence are not allowed. This affects the performance.

A number of techniques have been proposed to enable the use of certain optimizations by the hardware and compiler without violating sequential consistency, those having the potential to substantially boost performance. Some of them are mentioned below:

Hardware optimization techniques:

- Prefetching : It is hardware optimization technique in which the processor automatically prefetches ownership for any write operations that are delayed due to the program order requirement (e.g., by issuing prefetch-exclusive requests for any writes delayed

in the write buffer), thus partially overlapping the service of the delayed writes with the operations preceding them in program order. This technique is only applicable to cache-based systems that use an invalidation-based protocol. This technique is suitable for statically scheduled processors.

- Speculative Reads : It is a hardware optimization technique in which read operations that are delayed due to the program order requirement are serviced speculatively ahead of time. Sequential consistency is guaranteed by simply rolling back and reissuing the read and subsequent operations in the infrequent case that the read line gets invalidated or updated before the read could have been issued in a more straightforward implementation. This is suitable for dynamically scheduled processors since much

of the roll back machinery is already present to deal with branch mispredictions.

More information about these two techniques can be found in this paper presented by Kourosh Gharachorloo, Anoop Gupta, and John Hennessy of Stanford University at International Conference on Parallel Processing, Two techniques to enhance the performance of memory consistency models

These two techniques of Prefetching and Speculative Reads are expected to be supported by several next generation microprocessors like MIPS R10000 and Intel P6, thus enabling more efficient hardware implementations of sequential consistency.

Software Optimization techniques

- Shasha and Snir's agorithm : It is a compiler algorithm proposed by Dennis Shasha and Marc Snir and is used to detect when memory operations can be reordered without violating sequential consistency. It uses the technique where Sequential consistency can be enforced by delaying each access to shared memory until the previous access of the same processor has terminated. For performance reasons, it allows several accesses by the same processor to proceed concurrently. It performs an analysis to find a minimal set of delays that enforces sequential consistency. The analysis extends to interprocessor synchronization constraints and to code where blocks of operations have to execute atomically thus providing a new compiler optimization techniques for parallel languages that support shared variables.

In detail implementation of this algorithm can be studied from the paper : Efficient and correct execution of parallel programs that share memory

- Compiler algorithm for SPMD (Single Program multiple data) programs : The algorithm proposed by Sasha and Snir has exponential complexity. This new algorithm simplified the cycle detection analysis used in their algorithm to achieve the job in polynomial time.

More information about this can be found in this paper by Arvind Krishnamurthy and Katherine Yelick presented at 7th International Workshop on Languages and Compilers for Parallel Computing Optimizing parallel SPMD programs

In general the performance of sequential consistency model on multiprocessors with shared memory is low. But with the use of above techniques, better performance can be achieved.

All of the above schemes mentioned to improve performance of SC allow a processor to overlap or reorder its memory accesses without software support, however, either require complex or restricted hardware (e.g., hardware prefetching and rollback) or the gains are expected to be small. Further, the optimizations of these schemes can be exploited by hardware (or the runtime system software), but cannot be exploited by compilers. Work related to compiler optimizations including that by Shasha and Snir motivate their work for hardware optimizations. Hardware costs are thus high to implement these techniques.

Hence researchers and vendors have alternatively relied on relaxed memory consistency models that embed the shared-address space programming interface with directives enabling software to inform hardware when memory ordering is necessary.

Relaxed Consistency Models

Uniprocessor optimizations such as write buffers and overlapped execution can violate sequential consistency. Therefore, general implementations of sequential consistency require a processor to execute its memory operations one at a time in program order, and writes are executed atomically. Many schemes discussed in the previous section do not require memory operations of a processor to be executed one at a time or atomically. However, these schemes either require restricting the network, or using complex hardware, or aggressive compiler technology. Even so, the performance gains possible are not known. For these reasons, there seems to be an emerging consensus in the industry to support relaxed memory models. Many commercially available architectures such as Digital Alpha, SPARC V8 and V9, and IBM PowerPC are based on this model. Relaxed memory consistency models allow the processors in the system to see different orderings between all or selected categories of memory operations that are strictly enforced in SC. Relaxed consistency models perform better than SC, but impose extra burden on the programmer to ensure that their programs conform to the consistency models that the hardware provides.

Different Relaxed consistency Models

The various relaxed models can be categorized based on how they relax the program order constraint:

- Write to Read relaxation: allow a write followed by a read to execute out of program order . Examples of models that provide this relaxation includes the IBM-370 , Sun SPARC V8 Total Store Ordering (TSO), and Processor Consistency (PC) that we have seen in class.

- Write to Write relaxation: allows two writes to execute out of program order. The Sun SPARC V8 Partial Store Ordering (PSO) model relaxes two writes.

- Read to Read, Write: allows reads to execute out of program order with respect to their following reads and writes. The models that implement this relaxation include Digital Equipment Alpha (Alpha), Sun SPARC V9 Relaxed Memory Order (RMO), IBM PowerPC (PowerPC) and the weak ordering (WO) and release consistency (RC) models that we have seen in class.

Apart from the program order relaxation, some of these models also relax the write atomicity requirement.

- Read others’ write early: allow a read to return the value of another processor’s write before the write is made visible to all other processors. This relaxation only applies to cache-based systems.

- Read own write early: a processor is allowed to read the value of its own previous write before the write is made visible to other processors.

All of the above models provide safety net that allow programmers to enforce the required constraints for achieving correctness. All models also maintain uniprocessor data and control dependences, and write serialization.

Let us now see the consistency models in some of the real multiprocessor systems listed above. Apart from these we will only introduce only those topics that are not covered in the solihin textbook, like the two variations of release consistency models, RCsc and RCpc. RCsc maintains sequential consistency among synchronization operations, while RCpc maintains processor consistency among synchronization operations.

Relax Write to Read program order

Program order optimization is enabled by allowing a read to be reordered with respect to previous writes from the same processor and sequential consistency is maintained through the enforcement of the remaining program order constraints. Though relaxing the program order from a write followed by a read can improve performance, this reordering is not sufficient for compiler optimizations. The reason being most compiler optimizations require the full flexibility of reordering any two operations in program, and not just write to read. The models to be discussed under this type of relaxation differ in when they allow a read to return the value of a write.

IBM-370

The IBM-370 model relaxes certain writes to reads program order but maintains the atomicity requirements of SC. This model enforces the program order constraint from a write to a following read, by using the safety net serialization instructions that may be placed between the two operations. This model is the most stringent only next to SC because the program order from a write to a read still needs to be maintained in the below three cases:

- A write followed by a read to the same location [depicted by dashed line in between W and R in the figure].

- If either write or read are generated by a serialization instruction[ WS , RS].

- If there is a non-memory serialization instruction such as fence instruction[F] between the write and read.

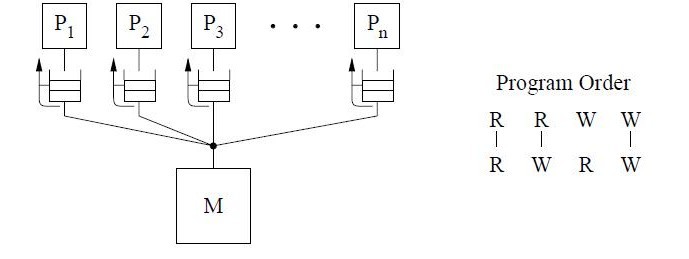

The conceptual system shown in the above figure is similar to that used for representing SC. The main difference is the presence of a buffer between each processor and the memory. Since we assume that each processor issues its operations in program order, we use the buffer to model the fact that the operations are not necessarily issued in the same order to memory. The cancelled reply path from the buffer to the processor implies that a read is not allowed to return the value of a writeto the same location from the buffer.

The IBM-370 model has two types of serialization instructions: special instructions that generate memory operations (e.g., compare-and-swap) and special non-memory instructions (e.g., a special branch).

SPARC V8 Total Store Ordering (TSO)

The total store ordering (TSO) model is one of the models proposed for the SPARC V8 architecture. TSO always allows a write followed by a read to complete out of program order, i.e reads issued to the same pending writes are allowed to be reordered. Read returns a previous write value if present, else fetches the value from the memory. All other program orders are maintained. This is shown in the conceptual system below by the reply path from the buffer to a read that is no longer blocked.

For TSO, a safety net for write atomicity is required only for a write that is followed by a read to the same location in the same processor. The atomicity can be achieved by ensuring program order from the write to the read using read-modify-writes.

Difference between IBM370 and TSO:

Let us consider the program segment below, taken from reference link http://infolab.stanford.edu/pub/cstr/reports/csl/tr/95/685/CSL-TR-95-685.pdf, to demonstrate the difference between TSO and IBM 370 models.

First consider the program segment in (a). Under the SC or IBM-370 model, the outcome (u,v,w,x)=(1,1,0,0) is disallowed. However, this outcome is possible under TSO because reads are allowed to bypass all previous writes, even if they are to the same location; therefore the sequence (b1,b2,c1,c2,a1,a2) is a valid total order for TSO. Of course, consistency value requirement still requires b1 and b2 to return the values of a1 and a2, respectively, even though the reads occur earlier in the sequence than the writes. This maintains the intuition that a read observes all the writes issued from the same processor as the read. Consider the program segment in (b). In this case, the outcome (u,v,w,x)=(1,2,0,0)is not allowed under SC or IBM-370, but is possible under TSO.

Relax Write to Write program order

Relax Read to Read and Read to Write program orders

Performance of Relaxed Consistency Models

References

- Speculative Sequential Consistency with Little Custom Storage

- Two techniques to enhance the performance of memory consistency models

- Optimizing parallel SPMD programs

- Efficient and correct execution of parallel programs that share memory

- Shared Memory Consistency Models

- Designing Memory Consistency Models For Shared-Memory Multiprocessors