CSC/ECE 517 Fall 2011/ch2 2e kt: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (48 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== | =Testing frameworks for Ruby= | ||

__TOC__ | |||

== Introduction == | |||

Due to the rapid expansion in the use of Ruby through Ruby on Rails, the landscape of the Ruby testing framework has changed dramatically in recent years. Because of this, it provides a great story in the evolution of these testing frameworks. | |||

== Evolution of Testing Architectures == | == Evolution of Testing Architectures == | ||

| Line 9: | Line 12: | ||

=== Behavior Driven Development === | === Behavior Driven Development === | ||

Behavior Driver Development (or BDD) arose out of the fact that tests written in the TDD style are only clearly readable by the coders themselves. If a project manager without programming knowledge were to look at the tests as a description of the functionality to be provided, this would not very meaningful. BDD evolved though the idea that the tests could be written in such a way as to provide a set of project requirements and functions that is readable by the average person. This allows the tests to not only act as the testing framework for a project but also as an executable requirement list. This style still leverages the TDD development cycle benefits with the added readability for those outside of the development team. It should be noted that there is often a small learning curve associated with BDD testing frameworks compared to TDD | Behavior Driver Development (or BDD), originally proposed by Dan North<ref name = dannorth />, arose out of the fact that tests written in the TDD style are only clearly readable by the coders themselves. If a project manager without programming knowledge were to look at the tests as a description of the functionality to be provided, this would not very meaningful. BDD evolved though the idea that the tests could be written in such a way as to provide a set of project requirements and functions that is readable by the average person. This allows the tests to not only act as the testing framework for a project but also as an executable requirement list. This style still leverages the TDD development cycle benefits with the added readability for those outside of the development team. It should be noted that there is often a small learning curve associated with BDD testing frameworks compared to TDD. | ||

== Ruby Testing Frameworks == | == Ruby Testing Frameworks == | ||

Some of the more popular Ruby testing frameworks include<ref | Some of the more popular Ruby testing frameworks include<ref name = rubytool />: | ||

* [[#Test::Unit|Test::Unit]] | * [[#Test::Unit|Test::Unit]] | ||

* [[#Mini::Test|Mini::Test]] | * [[#Mini::Test|Mini::Test]] | ||

| Line 45: | Line 48: | ||

end | end | ||

end | end | ||

[[#top|Back to top]] | |||

=== <u>Test::Unit</u> === | === <u>Test::Unit</u> === | ||

==== Overview ==== | ==== Overview ==== | ||

Test::Unit was one of the first widely adopted testing frameworks for Ruby, even being included as part of the standard library as of version 1.8. It is based on the SUnit Smalltalk framework <ref | Test::Unit was one of the first widely adopted testing frameworks for Ruby, even being included as part of the standard library as of version 1.8. It is based on the SUnit Smalltalk framework <ref name = progruby /> and is very similar to testing frameworks in other languages such as JUnit (Java) and NUnit (.NET). The Test::Unit framework falls under the category of a Test Driven Design framework and relies on creating test cases, under which reside test methods. An individual test case consists of a class which inherits from '''Test::Unit::TestCase''' and contains test methods which, together, usually test a particular function or feature. Within each test case, only methods starting with the name "test" are automatically run, with the exception of the optional '''setup''' or '''teardown''' methods. These methods can be used to initialize and clean up any structures which may be used across the test methods. As of Ruby 1.9, Test::Unit has been replaced by Mini::Test as the testing framework included in the standard library. | ||

==== Functionality ==== | ==== Functionality ==== | ||

| Line 130: | Line 135: | ||

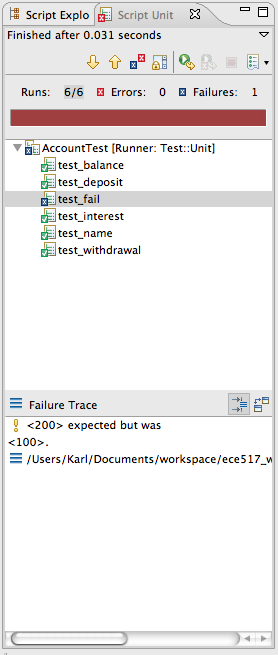

Here we can see that in total all 6 test methods were run with one of them failing. The failing test method is indicated by name with the code line, expected output and actual output. | Here we can see that in total all 6 test methods were run with one of them failing. The failing test method is indicated by name with the code line, expected output and actual output. | ||

[[#top|Back to top]] | |||

=== <u>Mini::Test</u> === | === <u>Mini::Test</u> === | ||

| Line 137: | Line 144: | ||

Mini::Test is one of the more recent additions to the Ruby Testing frameworks. Mini::Test was created to be a small, clean and fast replacement for the [[#Test::Unit|Test::Unit]] framework. | Mini::Test is one of the more recent additions to the Ruby Testing frameworks. Mini::Test was created to be a small, clean and fast replacement for the [[#Test::Unit|Test::Unit]] framework. | ||

As previously mentioned, | As previously mentioned, Mini::Test is included in the standard library as of Ruby 1.9. (If you are running Ruby 1.8, you can run [http://rubygems.org/gems/minitest gem install minitest] to get Mini::Test. Alternately, you can install the [http://rubygems.org/gems/test-unit test-unit gem] if you have Ruby 1.9 and want to get the Test::Unit functionality.) Mini::Test provides both a Test Driven Development framework and a Behavior Driven Development Framework. Test cases in MiniTest::Unit are built similarly to those in Test::Unit - you create test cases with test methods containing assertions along with optional setup and teardown methods . Mini/spec (the BDD component of Mini::Test) borrowed concepts from existing BDD frameworks, such as RSpec and Shoulda. Test cases are created using expectations instead of assertions (see [[#Code Example - mini/spec|Code Example - mini/spec]] below for details). | ||

Because Mini::Test was based on familiar frameworks, using it is realtively intuitive. As creator, Ryan Davis says, "There is no magic". (View Ryan's [http://confreaks.net/videos/618-cascadiaruby2011-size-doesn-t-matter presentation on Mini::Test] at the Cascadia Ruby 2011 conference.) Mini::Test is simple and straightforward. | Because Mini::Test was based on familiar frameworks, using it is realtively intuitive. As creator, Ryan Davis says, "There is no magic". (View Ryan's [http://confreaks.net/videos/618-cascadiaruby2011-size-doesn-t-matter presentation on Mini::Test] at the Cascadia Ruby 2011 conference.) Mini::Test is simple and straightforward. | ||

| Line 197: | Line 204: | ||

def setup | def setup | ||

@a = Account.new(100) | |||

end | end | ||

| Line 211: | Line 218: | ||

@a.name = "Checking" | @a.name = "Checking" | ||

refute_nil(@a.name()) | refute_nil(@a.name()) | ||

assert_match(@a.name | assert_match("Checking", @a.name) | ||

end | end | ||

def test_interest | def test_interest | ||

assert_in_delta(@a.addinterest(0.333) | assert_in_delta(130, @a.addinterest(0.333), 5) | ||

end | end | ||

def test_fail | def test_fail | ||

assert_equal(@a.balance() | assert_equal(200, @a.balance()) | ||

end | end | ||

def test_whatru | def test_whatru | ||

assert_instance_of(Account, @a) | |||

end | end | ||

| Line 237: | Line 244: | ||

1) Failure: | 1) Failure: | ||

test_fail(AccountTest) [C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test_account2.rb:30]: | test_fail(AccountTest) [C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test_account2.rb:30]: | ||

Expected | Expected 200, not 100. | ||

6 tests, 8 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips | 6 tests, 8 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips | ||

| Line 324: | Line 331: | ||

==== Overview ==== | ==== Overview ==== | ||

RSpec is a BDD testing framework that is built on top of Unit::Test and is one of the more popular unit testing frameworks<ref | RSpec is a BDD testing framework that is built on top of Unit::Test and is one of the more popular unit testing frameworks<ref name = rubytool />. While it provides much of the same unit testing functionality, it's syntax is much different than that of Unit::Test. First of all, as a BDD framework, RSpec does not have test methods but rather a set of sentences describing each test case. Nested in each sentence is the code to complete the test. All of these sentences are contained under a "describe" block which houses sentences testing a common functionality or feature, similar to a test case class in Unit::Test. It also provides verbose test output which can be exported in a number of ways, including a requirements list. | ||

==== Functionality ==== | ==== Functionality ==== | ||

| Line 407: | Line 414: | ||

Take note of the test sentences printed out in the documentation format at the top, each listing the status of the test in a humanly readable fashion. We also have more verbose output on the tests which failed and are pending. | Take note of the test sentences printed out in the documentation format at the top, each listing the status of the test in a humanly readable fashion. We also have more verbose output on the tests which failed and are pending. | ||

[[#top|Back to top]] | |||

=== <u>Shoulda</u> === | === <u>Shoulda</u> === | ||

| Line 422: | Line 431: | ||

end | end | ||

Shoulda test cases require ''''test/unit'''' as well as ''''shoulda''''. Shoulda provides '''setup do''' and '''teardown do''' as well as '''context do''' methods. Contexts give the programmer the ability to create blocks of code that have something in common. Each context can have its own setup and contexts can be nested. This means that test cases can perform setup for all tests and an additional setup that applies to just a subset of the tests. The format for context statement is similar to that of the should statement: | Shoulda test cases require ''''test/unit'''' as well as ''''shoulda''''. Shoulda provides '''setup do''' and '''teardown do''' as well as '''context do''' methods. Contexts give the programmer the ability to create blocks of code that have something in common. Each context can have its own setup and contexts can be nested. This means that test cases can perform setup for all tests and an additional setup that applies to just a subset of the tests. The format for the context statement is similar to that of the should statement: | ||

context "Test Group 1" do | context "Test Group 1" do | ||

| Line 430: | Line 439: | ||

====Code Example==== | ====Code Example==== | ||

Since Shoulda creates Test::Unit methods for each '''should''' block<ref | Since Shoulda creates Test::Unit methods for each '''should''' block<ref name = progruby />, AccountTest must inherit from Test::Unit::TestCase. Each test is a combination of descriptive '''should''' statements and Test::Unit unit tests. In this example, we have added a unit test method - '''assert_correct''' - and then used that assertion within the Shoulda framework. This code also contains two contexts - with one nested inside the other. The first provides the setup to create the account (needed for all tests), while the second creates a name for the account (needed only for the "Have Name" test). | ||

require 'test/unit' | require 'test/unit' | ||

| Line 460: | Line 469: | ||

should "Add interest to account correctly" do | should "Add interest to account correctly" do | ||

assert_in_delta(@a.addinterest(0.333) | assert_in_delta(130, @a.addinterest(0.333), 5) | ||

end | end | ||

should "Fail Test" do | should "Fail Test" do | ||

assert_equal(@a.balance() | assert_equal(200, @a.balance()) | ||

end | end | ||

| Line 478: | Line 487: | ||

should "Have name" do | should "Have name" do | ||

assert_not_nil(@a.name()) | assert_not_nil(@a.name()) | ||

assert_match(@a.name | assert_match("Checking", @a.name()) | ||

end | end | ||

end | end | ||

| Line 493: | Line 502: | ||

1) Failure: | 1) Failure: | ||

test: Basic Account Functions should Fail Test. (AccountTest) [C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test3a.rb:33]: | test: Basic Account Functions should Fail Test. (AccountTest) [C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test3a.rb:33]: | ||

< | <200> expected but was | ||

< | <100>. | ||

7 tests, 8 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips | 7 tests, 8 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips | ||

| Line 506: | Line 515: | ||

==== Overview ==== | ==== Overview ==== | ||

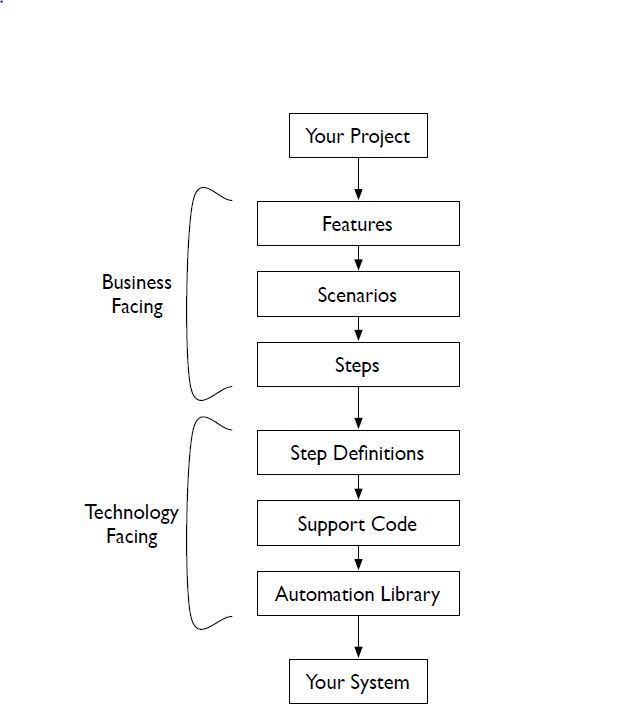

Cucumber | Cucumber was released in 2008 to address some of the problems with RSpec’s Story Runner and was designed for behavior driven development. (RSpec's Story Runner is an integration testing tool that allows the user to create executable user stories or scenarios.) Cucumber performs automated tests that have been developed using functional descriptions. The language that Cucumber uses is [http://github.com/cucumber/cucumber/wiki/Gherkin Gherkin]. Gherkin files have a set of special keywords to form its structure. The Gherkin basic structure looks something like the following: | ||

Feature: This is the feature title | Feature: This is the feature title | ||

| Line 517: | Line 526: | ||

Then this state #the outcomes (s) | Then this state #the outcomes (s) | ||

This is | This in turn is translated into a regular expression for each of the step definitions. For each regular expression, the programmer then defines the action he would like for his program to implement. Once these definitions and actions have been established, then the class can be built. This process embodies the outside-in philosophy of behaviour driven development. Cucumber is quite extensive. It is not just a testing framework, however, it is a total approach to programming. According to the [http://cukes.info/ Cucumber website], the basic process is: | ||

# Describe behavior in plain text | # Describe behavior in plain text | ||

| Line 536: | Line 545: | ||

In order to test my Account program | In order to test my Account program | ||

As a Developer | As a Developer | ||

I want to | I want to perform Account functions | ||

Scenario: Withdrawal Scenario | Scenario: Withdrawal Scenario | ||

| Line 564: | Line 573: | ||

[[Image:Cucumber.JPG]] | [[Image:Cucumber.JPG]] | ||

There is quite a bit of setup to run Cucumber. There is a very easy to follow tutorial at [http://cuke4ninja.com/download.html The Secret Ninja Cucumber Scrolls]. | There is quite a bit of setup to run Cucumber. There is a very easy to follow tutorial at [http://cuke4ninja.com/download.html The Secret Ninja Cucumber Scrolls] and the Cucumber [http://cukes.info/ website] has a plethora of information. | ||

[[#top|Back to top]] | |||

== Conclusion== | |||

Testing has always been an integral part of the Ruby landscape. This culture of testing has given rise to a variety of different testing frameworks. In this article we have reviewed only a few of the most popular offerings<ref name = rubytool /> representing both the Test Driven Development and Behavior Driven Development styles. The matrix below provides a summary of the tools highlighted on this page. Should none of these frameworks meet the Ruby programmer's needs, there are currently a number of others with more being developed every day. See the [http://ruby-toolbox.com/categories/testing_frameworks.html Ruby Toolbox] for a list of additional Ruby testing options. | |||

== Framework Matrix == | ===Framework Matrix === | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="font-size: 100%; text-align: left; width: auto;" | {| class="wikitable" style="font-size: 100%; text-align: left; width: auto;" | ||

| Line 588: | Line 594: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| ''' Unit::Test''' | | ''' Unit::Test''' | ||

| | |[http://www.ruby-doc.org/stdlib-1.8.6/libdoc/test/unit/rdoc/classes/Test/Unit.html RubyDoc] | ||

|[http://www.ruby-doc.org/stdlib-1.8. | |[http://www.ruby-doc.org/stdlib-1.8.6/libdoc/test/unit/rdoc/classes/Test/Unit.html RubyDoc] | ||

|Eclipse, RubyMine | |Eclipse, RubyMine | ||

|TDD | |TDD | ||

|Easy to learn; | |Easy to learn; Easy to use | ||

|- | |- | ||

| ''' MiniTest::Unit ''' | | ''' MiniTest::Unit ''' | ||

| Line 606: | Line 612: | ||

|Eclipse, RubyMine | |Eclipse, RubyMine | ||

|BDD | |BDD | ||

|Slightly more difficult to learn; Easy to use | |Slightly more difficult to learn due to BDD topology; Easy to use | ||

|- | |- | ||

| ''' Shoulda ''' | | ''' Shoulda ''' | ||

| [http://github.com/thoughtbot/shoulda GitHub] | | [http://github.com/thoughtbot/shoulda GitHub] | ||

| [http://rdoc.info/github/thoughtbot/shoulda/master/frames RubyDoc] | | [http://rdoc.info/github/thoughtbot/shoulda/master/frames RubyDoc] | ||

| Eclipse | | Eclipse, RubyMine | ||

| | |BDD | ||

| Easy to learn; Easy to use | | Easy to learn; Easy to use | ||

|- | |- | ||

| ''' Cucumber ''' | | ''' Cucumber ''' | ||

| [http://cukes.info/ Cucumber] | | [http://cukes.info/ Cucumber] | ||

| | | [http://github.com/cucumber/cucumber/wiki/_pages Cucumber Wiki] | ||

| | | RubyMine | ||

| | | BDD | ||

| | | Steeper learning curve; Complexity makes use a bit more challenging | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 626: | Line 632: | ||

<references> | <references> | ||

<ref name = dannorth> http://dannorth.net/introducing-bdd </ref> | <ref name = dannorth> http://dannorth.net/introducing-bdd </ref> | ||

<ref name = rubytool> http://ruby-toolbox.com/categories/testing_frameworks.html </ref> | |||

<ref name = progruby> Programming Ruby: The Pragmatic Programmers' Guide, Second Ed. </ref> | |||

</references> | </references> | ||

Latest revision as of 13:00, 1 October 2011

Testing frameworks for Ruby

Introduction

Due to the rapid expansion in the use of Ruby through Ruby on Rails, the landscape of the Ruby testing framework has changed dramatically in recent years. Because of this, it provides a great story in the evolution of these testing frameworks.

Evolution of Testing Architectures

Across all of the testing frameworks that Ruby has, most of them fall into two categories: Test Driven Development and Behavior Driven Development. These two types of development styles helped to drive the evolution of the Ruby testing frameworks we will be discussing.

Test Driven Development

Test Driven Development (or TDD) is a development style that relies on writing the tests for a given program first, thereby establishing the functionality, then proceeding to write the code to fulfill that criteria. As the code is being written, the tests can be run and examined, thus providing status on the development of the features. Once all of the tests pass for a given function, the development is complete and any refactoring can be done before finalizing the code. TDD has the benefit of providing for a short development cycle and encouraging simple designs. However, there are some shortcomings which have lead to the creation of the Behavior Development Cycle.

Behavior Driven Development

Behavior Driver Development (or BDD), originally proposed by Dan North<ref name = dannorth />, arose out of the fact that tests written in the TDD style are only clearly readable by the coders themselves. If a project manager without programming knowledge were to look at the tests as a description of the functionality to be provided, this would not very meaningful. BDD evolved though the idea that the tests could be written in such a way as to provide a set of project requirements and functions that is readable by the average person. This allows the tests to not only act as the testing framework for a project but also as an executable requirement list. This style still leverages the TDD development cycle benefits with the added readability for those outside of the development team. It should be noted that there is often a small learning curve associated with BDD testing frameworks compared to TDD.

Ruby Testing Frameworks

Some of the more popular Ruby testing frameworks include<ref name = rubytool />:

Since this will be a comparison across the different frameworks listed, using a common class to test against will provide us with a baseline for our comparisons. As such, we will use the following class implementing a bank account:

class Account

@balance

@name

attr_accessor :balance

attr_accessor :name

def initialize(amount)

@balance = amount

end

def deposit(amount)

@balance += amount

end

def addinterest(rate)

@balance *= (1 + rate)

end

def withdrawal(amount)

@balance -= amount

end

end

Test::Unit

Overview

Test::Unit was one of the first widely adopted testing frameworks for Ruby, even being included as part of the standard library as of version 1.8. It is based on the SUnit Smalltalk framework <ref name = progruby /> and is very similar to testing frameworks in other languages such as JUnit (Java) and NUnit (.NET). The Test::Unit framework falls under the category of a Test Driven Design framework and relies on creating test cases, under which reside test methods. An individual test case consists of a class which inherits from Test::Unit::TestCase and contains test methods which, together, usually test a particular function or feature. Within each test case, only methods starting with the name "test" are automatically run, with the exception of the optional setup or teardown methods. These methods can be used to initialize and clean up any structures which may be used across the test methods. As of Ruby 1.9, Test::Unit has been replaced by Mini::Test as the testing framework included in the standard library.

Functionality

As Test::Unit is a Test Driven Development framework, it provides many of the low level testing constructs that you would expect to find in similar frameworks. It primarily relies on simple assertions to verify test cases. The functionality of Test::Unit is considered to be one of the more simple frameworks and, as such, one of the easier to learn.

| assert | assert_nil | assert_not_nil | assert_equal | assert_not_equal |

| assert_in_delta | assert_raise | assert_nothing_raised | assert_instance_of | assert_kind_of |

| assert_respond_to | assert_match | assert_no_match | assert_same | assert_not_same |

| assert_operator | assert_throws | assert_send | flunk |

Test::Unit allows for the creation of test suites, which are collections of test cases, allowing for a higher level grouping of tests. Such test suites can be produced by creating a file which requires 'test/unit' as well as any other files which contain test cases.

When a test is usually run, it is called via ruby against the file containing the test case. In some cases, we wish to modify the way the test results are output; this is where a part of Test::Unit called "test runners" come in. These test runners allow the output of the test cases to be modified by overriding the default output methods. In this way, test outputs can be easily modified to fit new testing environments or even integration into IDEs.

Code Example

In order to create a test case for the Account class mentioned earlier, one needs to create a new class which inherits from Test::Unit::TestCase and requires 'test/unit' as well as the class under test, in this case 'Account.rb'. In order to get the test results, one simply has to run the ruby interpreter against the test file. For this example, we also include a failing test in order to point out the information provided in the event of a failed test.

require "test/unit"

require_relative("../Account.rb")

class AccountTest < Test::Unit::TestCase

def test_balance

a = Account.new(100)

assert_equal(100, a.balance())

end

def test_deposit

a = Account.new(100)

assert_equal(200, a.deposit(100))

end

def test_withdrawal

a = Account.new(100)

assert_equal(50, a.withdrawal(50))

end

def test_name

a = Account.new(100)

a.name = "Checking"

assert_not_nil(a.name())

end

def test_interest

a = Account.new(100)

assert_equal(150, a.addinterest(0.5))

end

def test_fail

a = Account.new(100)

assert_equal(200, a.balance())

end

end

From this we will get the output:

Loaded suite AccountTest-ut Started ..F... Finished in 0.000782 seconds. 1) Failure: test_fail(AccountTest) [AccountTest-ut.rb:40]: <200> expected but was <100>. 6 tests, 6 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips

Here we can see that in total all 6 test methods were run with one of them failing. The failing test method is indicated by name with the code line, expected output and actual output.

Mini::Test

Overview

Mini::Test is one of the more recent additions to the Ruby Testing frameworks. Mini::Test was created to be a small, clean and fast replacement for the Test::Unit framework.

As previously mentioned, Mini::Test is included in the standard library as of Ruby 1.9. (If you are running Ruby 1.8, you can run gem install minitest to get Mini::Test. Alternately, you can install the test-unit gem if you have Ruby 1.9 and want to get the Test::Unit functionality.) Mini::Test provides both a Test Driven Development framework and a Behavior Driven Development Framework. Test cases in MiniTest::Unit are built similarly to those in Test::Unit - you create test cases with test methods containing assertions along with optional setup and teardown methods . Mini/spec (the BDD component of Mini::Test) borrowed concepts from existing BDD frameworks, such as RSpec and Shoulda. Test cases are created using expectations instead of assertions (see Code Example - mini/spec below for details).

Because Mini::Test was based on familiar frameworks, using it is realtively intuitive. As creator, Ryan Davis says, "There is no magic". (View Ryan's presentation on Mini::Test at the Cascadia Ruby 2011 conference.) Mini::Test is simple and straightforward.

Functionality

Most of the assertions in Mini::Test::TestCase are the same as those in its predecessor with some new ones added. The most notable difference is in the negative assertions. In Test::Unit where you have an assert_not_something method, Mini::Test gave them a streamlined name of a refute_something method. (assert_not_raise and assert_not_throws are no longer available.) Mini::Test::Unit provides the following assertions:

| assert | assert_block | assert_empty | refute | refute_empty | |

| assert_equal | assert_in_delta | assert_in_epsilon | refute_equal | refute_in_delta | refute_in_epsilon |

| assert_includes | assert_instance_of | assert_kind_of | refute_includes | refute_instance_of | refute_kind_of |

| assert_match | assert_nil | assert_operator | refute_match | refute_nil | refute_operator |

| assert_respond_to | assert_same | assert_output | refute_respond_to | refute_same | |

| assert_raises | assert_send | assert_silent | assert_throws |

While mini/spec contains the following expectations:

| must_be | must_be_close_to | must_be_empty | wont_be | wont_be_close_to | wont_be_empty |

| must_be_instance_of | must_be_kind_of | must_be_nil | wont_be_instance_of | wont_be_kind_of | wont_be_nil |

| must_be_same_as | must_be_silent | must_be_within_delta | wont_be_same_as | wont_be_within_delta | |

| must_be_within_epsilon | must_equal | must_include | wont_be_within_epsilon | wont_equal | wont_include |

| must_match | must_output | must_raise | wont_match | ||

| must_respond_to | must_send | must_throw | wont_respond_to |

Additional Features

Aside from the API improvements, Mini::Test also provides some additional features such as test randomization. In unit testing, tests should run independent from each other (i.e. the outcome or resulting state(s) of one test should not affect another). By randomizing the order, Mini::Test prevents tests from becoming order-dependent. Should you need to repeat a particular order to test for such issues, Mini::Test provides the current seed as part of the output and gives you the option to run the test using this same seed.

Mini::Test also gives you the ability to skip tests that are not working correctly (for debug at a later time) as well as additional options for determining the performance of your test suite.

Code Example - Mini::Test:Unit

We follow the same steps to create a test case for our Account class that we did in Test::Unit Code Example , except that this class inherits from MiniTest:Unit::TestCase and requires 'minitest/autorun'. (Requiring minitest/unit does not cause the test methods to be automatically invoked when the test case is run, hence we use minitest/autorun which provides this functionality.) We also need to update the assertions to those provided with MiniTest - for this class the assert_not_nil was changed to refute_nil. The AccountTest test case is below.

require 'minitest/autorun'

require_relative 'account.rb'

class AccountTest < MiniTest::Unit::TestCase

def setup

@a = Account.new(100)

end

def test_deposit

assert_equal(200, @a.deposit(100))

end

def test_withdrawal

assert_equal(50, @a.withdrawal(50))

end

def test_name

@a.name = "Checking"

refute_nil(@a.name())

assert_match("Checking", @a.name)

end

def test_interest

assert_in_delta(130, @a.addinterest(0.333), 5)

end

def test_fail

assert_equal(200, @a.balance())

end

def test_whatru

assert_instance_of(Account, @a)

end

end

Executing this test case gives the following results, showing that 6 tests were run with 1 faliure. Information is provided about the failure, including test name, expected output and actual output. Note that the seed value of the random test run is also provided.

Loaded suite C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test_account2 Started .F.... Finished in 0.001000 seconds. 1) Failure: test_fail(AccountTest) [C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test_account2.rb:30]: Expected 200, not 100. 6 tests, 8 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips Test run options: --seed 13360

Code Example - mini/spec

To create a test case using mini/spec, test assertions are changed to spec expectations. The format for each "test" becomes:

describe "test" do

it "should do something"

spec expectation statment

end

end

This is the behaviour driven method of stating expectations instead of testing result values. The method def is replaced with a describe/it "should..." statement. Instead of using assert statements to check the action performed on the object, the action is performed and required (expected) to meet a given criteria. The setup and teardown functionalities are implemented using "before do" and "after do". The inherit statement is no longer used, but the require 'minitest/autorun' is. Each method is then converted to its spec counterpart using the above format and the appropriate expectations. The mini/spec test for the Account class is below.

require 'minitest/autorun'

require_relative 'account.rb'

describe Account do

before do

@a = Account.new(100)

end

describe "deposit" do

it "should add amount to balance" do

@a.deposit(100).must_equal 200

end

end

describe "withdraw" do

it "should subtract amount from balance" do

@a.withdrawal(50).must_equal 50

end

end

describe "set name" do

it "should set account name" do

@a.name = "Checking"

@a.name.wont_be_nil

@a.name.must_match "Checking"

end

end

describe "interest" do

it "should add interest to balance" do

@a.addinterest(0.333).must_be_within_delta(130, 5)

end

end

describe "fail" do

it "should fail" do

@a.balance.must_equal 200

end

end

describe "what are you" do

it "should be an instance of Account" do

@a.must_be_instance_of Account

end

end

end

The results are similar to previous tests, giving information on failures. Note that once again the randomization seed is given (and is different from previous test case).

Loaded suite C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test_account3 Started .F.... Finished in 0.003000 seconds. 1) Failure: test_0001_should_fail(AccountSpec::FailSpec) [C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test_account3.rb:39]: Expected 200, not 100. 6 tests, 8 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips Test run options: --seed 21728

RSpec

Overview

RSpec is a BDD testing framework that is built on top of Unit::Test and is one of the more popular unit testing frameworks<ref name = rubytool />. While it provides much of the same unit testing functionality, it's syntax is much different than that of Unit::Test. First of all, as a BDD framework, RSpec does not have test methods but rather a set of sentences describing each test case. Nested in each sentence is the code to complete the test. All of these sentences are contained under a "describe" block which houses sentences testing a common functionality or feature, similar to a test case class in Unit::Test. It also provides verbose test output which can be exported in a number of ways, including a requirements list.

Functionality

As mentioned above, each individual test is described by a sentence. These sentences start with the word "it", followed by a description of functionality that is to be tested, ending with a "do". Under each sentence, the actual testing code is written, where it is checked against a "should" statement. The describe method contains the plain english name of the function that we are testing, followed by all of the test sentences. RSpec also support before and after blocks which allow for consolidating common code that would normally be replicated in each test sentence. This could be used, for instance, to initialize the object under test for each test sentence all at once, as shown below. It also supports marking a test as pending which allows the developer to specify unfinished or broken functionality without failing a test.

Instead of using assert methods and it's variants, RSpec uses should statements. These statements consist of the object under test, followed by the method under test, the should modifier, and a query method or comparison. For example, the following code would test to see if the mileage method of the car object returns 12000.

@car.mileage.should == 12000

It is this format that makes it very intuitive as to which is the expected and which is the actual value. In the case of assert_equal in Unit::Test, this is not immediately clear as the differentiation is positional. For a more extensive display of RSpec's syntax, we have the example code below.

Code Example

In order to generate the following output, the command rspec is run against the test file.

require_relative("../Account.rb")

describe "The Account" do

before(:each) do

@a = Account.new(100)

end

it "should be created with a balance" do

@a.balance.should == 100

end

it "should take a deposit" do

@a.deposit(100).should == 200

end

it "should be capable of withdrawals" do

@a.withdrawal(50).should == 50

end

it "should have a name" do

@a.name = "Checking"

@a.name.should == "Checking"

end

it "should calculate interest" do

@a.addinterest(0.5).should == 150

end

it "should have a failure here as an example" do

@a.balance.should == 200

end

it "should provide a bank statement" do

pending "Not yet implemented"

end

end

Running the above code with the '--format doc' option we will get the output:

The Account

should be created with a balance

should take a deposit

should be capable of withdrawals

should have a name

should calculate interest

should have a failure here as an example (FAILED - 1)

should provide a bank statement (PENDING: Not yet implemented)

Pending:

The Account should provide a bank statement

# Not yet implemented

# ./AccountTest-rspec.rb:33

Failures:

1) The Account should have a failure here as an example

Failure/Error: @a.balance.should == 200

expected: 200

got: 100 (using ==)

# ./AccountTest-rspec.rb:30:in `block (2 levels) in <top (required)>'

Finished in 0.00132 seconds

7 examples, 1 failure, 1 pending

Failed examples:

rspec ./AccountTest-rspec.rb:29 # The Account should have a failure here as an example

Take note of the test sentences printed out in the documentation format at the top, each listing the status of the test in a humanly readable fashion. We also have more verbose output on the tests which failed and are pending.

Shoulda

Overview

Shoulda isn't a complete testing framework - instead it works inside the existing frameworks of Test::Unit or RSpec. It combines the descriptive abilities of a BDD framework (on a scaled-down version) along with the unit tests of a TDD framework. A Shoulda test case can be comprised of Shoulda tests along with regular Test:Unit tests and RSpec tests. Shoulda gives programmers the ability to convert existing Test::Unit test suites with little work while using the Shoulda language to describe the tests. To install Shoulda run gem install shoulda

Functionality

Since Shoulda test cases are built on top of Test::Unit, all the assertions provided in Test::Unit are available in Shoulda. Shoulda test cases are a combination of descriptive statements and assertions. The basic test format is very simple and straight forward.

should "do something" do assert_whatever end

Shoulda test cases require 'test/unit' as well as 'shoulda'. Shoulda provides setup do and teardown do as well as context do methods. Contexts give the programmer the ability to create blocks of code that have something in common. Each context can have its own setup and contexts can be nested. This means that test cases can perform setup for all tests and an additional setup that applies to just a subset of the tests. The format for the context statement is similar to that of the should statement:

context "Test Group 1" do ... end

Code Example

Since Shoulda creates Test::Unit methods for each should block<ref name = progruby />, AccountTest must inherit from Test::Unit::TestCase. Each test is a combination of descriptive should statements and Test::Unit unit tests. In this example, we have added a unit test method - assert_correct - and then used that assertion within the Shoulda framework. This code also contains two contexts - with one nested inside the other. The first provides the setup to create the account (needed for all tests), while the second creates a name for the account (needed only for the "Have Name" test).

require 'test/unit'

require 'shoulda'

require_relative 'account.rb'

class AccountTest < Test::Unit::TestCase

def assert_correct(target)

assert_equal(target, @a.balance)

end

context "Basic Account Functions" do

setup do

@a = Account.new(100)

end

should "Have correct amount in Account" do

assert_correct(100)

end

should "Deposit funds correctly" do

assert_equal(200, @a.deposit(100))

end

should "Withdraw funds correctly" do

assert_equal(50, @a.withdrawal(50))

end

should "Add interest to account correctly" do

assert_in_delta(130, @a.addinterest(0.333), 5)

end

should "Fail Test" do

assert_equal(200, @a.balance())

end

should "be an instance of Account" do

assert_instance_of(Account, @a)

end

context "Add Name Testing" do

setup do

@a.name = "Checking"

end

should "Have name" do

assert_not_nil(@a.name())

assert_match("Checking", @a.name())

end

end

end

end

This gives us the familiar results below.

Loaded suite C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test3a Started ...F... Finished in 0.001000 seconds. 1) Failure: test: Basic Account Functions should Fail Test. (AccountTest) [C:/Users/Tracy2/Desktop/NCSU/CSC 541/Workspace/Account/test3a.rb:33]: <200> expected but was <100>. 7 tests, 8 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips Test run options: --seed 25476

Cucumber

Overview

Cucumber was released in 2008 to address some of the problems with RSpec’s Story Runner and was designed for behavior driven development. (RSpec's Story Runner is an integration testing tool that allows the user to create executable user stories or scenarios.) Cucumber performs automated tests that have been developed using functional descriptions. The language that Cucumber uses is Gherkin. Gherkin files have a set of special keywords to form its structure. The Gherkin basic structure looks something like the following:

Feature: This is the feature title This is the description of the feature, which can span over multiple lines. Scenario: What is going to happen Given this state #the context When this happens #the event Then this state #the outcomes (s)

This in turn is translated into a regular expression for each of the step definitions. For each regular expression, the programmer then defines the action he would like for his program to implement. Once these definitions and actions have been established, then the class can be built. This process embodies the outside-in philosophy of behaviour driven development. Cucumber is quite extensive. It is not just a testing framework, however, it is a total approach to programming. According to the Cucumber website, the basic process is:

- Describe behavior in plain text

- Write a step definition in Ruby

- Run and watch it fail

- Write code to make the step pass

- Run again and see the step pass

- Repeat steps 2-5 until green like a cuke

- Repeat 1-6 until the money runs out<ref>http://cukes.info/</ref>

There are a number of Cucumber resources including The Cucumber Book.

Code Example

In order to perform just a basic test on our Account class, we describe the desired outcome in a features file.

Feature: Account Test Feature

In order to test my Account program

As a Developer

I want to perform Account functions

Scenario: Withdrawal Scenario

Given I have $100 in my account

When I withdraw $50 from my account

Then I should have $50 left in my account

We then write regular expressions to define these steps and test the outcome of our withdrawal function.

require 'rspec/expectations' require_relative '../../account.rb' Given /^I have \$(\d+) in my account$/ do |amount| @a = Account.new(amount.to_i) end When /^I withdraw \$(\d+) from my account$/ do |withdraw| @a.withdrawal(withdraw.to_i) end Then /^I should have \$(\d+) left in my account$/ do |balance| balance.to_i.should == @a.balance end

From this we get the following output:

There is quite a bit of setup to run Cucumber. There is a very easy to follow tutorial at The Secret Ninja Cucumber Scrolls and the Cucumber website has a plethora of information.

Conclusion

Testing has always been an integral part of the Ruby landscape. This culture of testing has given rise to a variety of different testing frameworks. In this article we have reviewed only a few of the most popular offerings<ref name = rubytool /> representing both the Test Driven Development and Behavior Driven Development styles. The matrix below provides a summary of the tools highlighted on this page. Should none of these frameworks meet the Ruby programmer's needs, there are currently a number of others with more being developed every day. See the Ruby Toolbox for a list of additional Ruby testing options.

Framework Matrix

| Framework | Website | Documentation | IDE Integration | Type | Ease of Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit::Test | RubyDoc | RubyDoc | Eclipse, RubyMine | TDD | Easy to learn; Easy to use |

| MiniTest::Unit | GitHub | RubyDoc | Eclipse | TDD/BDD | Easy to learn; Easy to use |

| RSpec | http://rspec.info/ | http://rspec.info/ | Eclipse, RubyMine | BDD | Slightly more difficult to learn due to BDD topology; Easy to use |

| Shoulda | GitHub | RubyDoc | Eclipse, RubyMine | BDD | Easy to learn; Easy to use |

| Cucumber | Cucumber | Cucumber Wiki | RubyMine | BDD | Steeper learning curve; Complexity makes use a bit more challenging |

References

<references> <ref name = dannorth> http://dannorth.net/introducing-bdd </ref> <ref name = rubytool> http://ruby-toolbox.com/categories/testing_frameworks.html </ref> <ref name = progruby> Programming Ruby: The Pragmatic Programmers' Guide, Second Ed. </ref> </references>