CSC/ECE 517 Fall 2007/wiki1b 8 sa: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (54 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

= The Strategy Design Pattern, comparing a dynamic OO language to a static OO language = | |||

In this page we explore the differences in implementation and design of the Strategy design pattern between the dynamic Object-Oriented language Ruby and the static Object-Oriented language Java. | |||

= Definitions = | |||

== | == Design Patterns == | ||

A [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Design_pattern_(computer_science) design pattern] is a general repeatable solution to a commonly occurring problem in software design. A design pattern is neither a finished design nor a solution that can be transformed directly into code. It is a template on how to solve a problem that can be used in many different situations. Design patterns are more often use in [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Object-oriented Object-oriented] designs as they typically show relationships and interactions between classes or objects, without specifying the final application classes or objects that are involved. | |||

Note: Algorithms are not design patterns, algorithms solve computational problems and design patterns solve design problems. | |||

== | == Strategy Pattern == | ||

The Strategy Design Pattern defines a family of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algorithm algorithms], encapsulates each one, and makes them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it. | |||

The Strategy pattern lets one build software as a loosely coupled collection of interchangeable parts, in contrast to a monolithic, tightly coupled system. That loose coupling makes the software much more extensible, maintainable, and reusable. The strategy pattern is useful for situations where it is necessary to dynamically swap the algorithms used in an application. | |||

=== | === Structure === | ||

[[Image:Strategy-Example.jpg||Sort using Strategy]] | |||

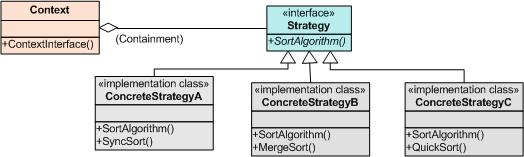

Normally there are 3 types of classes and or objects that participate in a strategy pattern implementation | |||

* Strategy | |||

: declares an interface common to all supported algorithms. Context uses this interface to call the algorithm defined by a ConcreteStrategy | |||

* ConcreteStrategy | |||

: implements the algorithm using the Strategy interface | |||

Note: | * Context | ||

: is configured with a ConcreteStrategy object | |||

: maintains a reference to a Strategy object | |||

: may define an interface that lets Strategy access its data. | |||

For example lets take the general case of sorting a list. One may wish to use different sort strategies based on the length of the list as performance of these sort algorithms vary depending on the size of the list. Here SortStrategy will be the common interface to all supported sort algorithms (like [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quicksort QuickSort], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merge_sort MergeSort], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bubble_sort Bubble Sort] etc.,) and SortedList will be the context that lets Strategy access the list and operate on it. | |||

=== Merits === | |||

# A family of algorithms can be defined as a class hierarchy and can be used interchangeably to alter application behavior without changing its architecture. | |||

# By encapsulating the algorithm separately, new algorithms complying with the same interface can be easily introduced. | |||

# The application can switch strategies at run-time. | |||

# Strategy enables the clients to choose the required algorithm, without using a "switch" statement or a series of "if-else" statements. | |||

# Data structures used for implementing the algorithm are completely encapsulated in Strategy classes. Therefore, the implementation of an algorithm can be changed without affecting the Context class. | |||

# Strategy Pattern can be used instead of sub-classing the Context class. Inheritance hardwires the behavior with the Context and the behavior cannot be changed dynamically. | |||

# The same Strategy object can be strategically shared between different Context objects. However, the shared Strategy object should not maintain states across invocations. | |||

=== Demerits === | |||

Note: Most of these demerits are specific to statically typed languages like Java. Use of dynamic object oriented languages like Ruby can help bypass these demerits | |||

# The application must be aware of all the strategies to select the right one for the right situation. | |||

# Context and the Strategy classes normally communicate through the interface specified by the abstract Strategy base class. Strategy base class must expose interface for all the required behaviors, which some concrete Strategy classes might not implement. | |||

# In most cases, the application configures the Context with the required Strategy object. Therefore, the application needs to create and maintain two objects in place of one. | |||

# Since, the Strategy object is created by the application in most cases; the Context has no control on lifetime of the Strategy object. However, the Context can make a local copy of the Strategy object. But, this increases the memory requirement and has a sure performance impact. | |||

=== Related Patterns === | |||

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Command_pattern Command] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bridge_Pattern Bridge] are two closely related patterns to Strategy. | |||

* A Command pattern encapsulates a single action, therefore it tends to have a single method with a rather generic signature. It often is intended to be stored for a longer time and to be executed later. Strategy, in contrast, is used to customize an algorithm. A strategy might have a number of methods specific to the algorithm. Most often strategies will be instantiated immediately before executing the algorithm, and discarded afterwards. | |||

* Bridge pattern is meant for structure, whereas the Strategy pattern is meant for behavior. The coupling between the context and the strategies is tighter than the coupling between the abstraction and the implementation in the Bridge pattern. | |||

== Alternatives == | === Alternatives === | ||

In some programming languages, such as those without polymorphism, the issues addressed by strategy pattern are handled through forms of reflection, such as the native function pointer or function delegate syntax. | In some programming languages, such as those without polymorphism, the issues addressed by strategy pattern are handled through forms of reflection, such as the native function pointer or function delegate syntax. | ||

= Example | = Real World Case Study = | ||

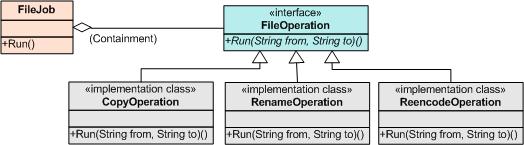

To demonstrate further let us consider an application that manages songs and playlists, and helps you copy/synchronize songs to you compact MP3 player or Mobile phone. The application accepts a playlist which has a catalog of MP3 files in different directories. | |||

Let critical actions performed on the files in playlist be renaming, copying or reencoding. Let each file to be copied/synchronized be represented by a <code>FileJob</code> object instance containing the source and destination paths. The actual action (rename/copy/reencode) that needs to be performed is given to the <code>FileJob</code> object as an instance of a class implementing the <code>FileOperation</code> interface. The application then has three different file operations: <code>CopyOperation</code>, <code>RenameOperation</code> and <code>ReencodeOperation</code>. Therefore, <code>FileJob</code> is the context class, the <code>FileOperation</code> interface is the strategy, and <code>CopyOperation</code>, <code>RenameOperation</code> and <code>ReencodeOperation</code> are concrete strategies. | |||

[[Image:Playlist-Example.jpg]] | |||

== Java's Solution == | |||

Here is the [http://java.sun.com/ Java] implementation of the playlist synchronization application. | |||

<pre> | |||

import java.util.ArrayList; | |||

// This is the Strategy interface | |||

interface FileOperation { | |||

public void Run(String from, String to); | |||

} | |||

// These are the three different implementations | |||

class CopyOperation implements FileOperation { | |||

public void Run(String from, String to) { | |||

System.out.println("Copy " + from + " to " + to + "."); | |||

} | |||

} | |||

class ReencodeOperation implements FileOperation { | |||

private int bitRate_; // In kbps | |||

ReencodeOperation(int bitRate) { | |||

bitRate_ = bitRate; | |||

} | |||

public void Run(String from, String to) { | |||

System.out.println("Reencode " + from + " to " + to + " at " + bitRate_ + "kbps."); | |||

} | |||

} | |||

class RenameOperation implements FileOperation { | |||

public void Run(String from, String to) { | |||

System.out.println("Rename " + from + " to " + to + "."); | |||

} | |||

} | |||

// This is the context class | |||

class FileJob { | |||

String from_; | |||

String to_; | |||

FileOperation op_; | |||

public FileJob(String from, String to, FileOperation op) { | |||

from_ = from; | |||

to_ = to; | |||

op_ = op; | |||

} | |||

void Run() { | |||

op_.Run(from_, to_); | |||

} | |||

} | |||

// Sample code | |||

class Test { | |||

public static void main(String[] args) { | |||

ArrayList<FileJob> jobs = new ArrayList<FileJob>(); | |||

FileOperation copyOp = new CopyOperation(); | |||

FileOperation renameOp = new RenameOperation(); | |||

FileOperation reencodeOp = new ReencodeOperation(128); // kbps | |||

jobs.add(new FileJob("file1", "file2", copyOp)); | |||

jobs.add(new FileJob("file3", "file4", renameOp)); | |||

jobs.add(new FileJob("file5", "file6", reencodeOp)); | |||

for (FileJob j : jobs) { | |||

j.Run(); | |||

} | |||

} | |||

} | |||

</pre> | |||

== Ruby's Solution == | == Ruby's Solution == | ||

Here is the [http://www.ruby-lang.org/en/ Ruby] implementation of the playlist synchronization application. | |||

<pre> | |||

# To give the file operation invocation a better name we define an alias, note | |||

# that this is optional, one can just use 'call', but it is better to adapt | |||

# the name to the problem domain | |||

class FileOperation < Proc | |||

alias_method :run, :call | |||

end | |||

# These are the strategies | |||

copyOp = FileOperation.new { |from, to| puts "Copy #{from} to #{to}." } | |||

renameOp = FileOperation.new { |from, to| puts "Rename #{from} to #{to}." } | |||

bitRate = 128 # kbps | |||

reencodeOp = FileOperation.new { |from, to| puts "Reencode #{from} to #{to} at #{bitRate}kbps." } | |||

# This is the context class | |||

class FileJob | |||

def initialize(from, to, op) | |||

@from = from | |||

@to = to | |||

@op = op | |||

end | |||

def run | |||

@op.run(@from, @to) | |||

end | |||

end | |||

# The same test as the Java implementation | |||

jobs = Array.new | |||

jobs << FileJob.new("file1", "file2", copyOp); | |||

jobs << FileJob.new("file3", "file4", renameOp); | |||

jobs << FileJob.new("file5", "file6", reencodeOp); | |||

jobs.each { |j| j.run() } | |||

</pre> | |||

= Java versus Ruby = | = Java versus Ruby = | ||

== | == Comparison == | ||

Let us perform a comparison to better understand the implementation | |||

{| border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="5" align="center" | |||

! Java's Strategy Implementation | |||

! Ruby's Strategy Implementation | |||

|- | |||

| An interface declaration, defines a common interface to the | |||

algorithm family | |||

| No interface declaration required | |||

|- | |||

| A class is required for each strategy implementation | |||

| No classes required, closures are good enough | |||

|- | |||

| Algorithms for strategies need to be defined at compile time | |||

| New algorithms for strategies can be created on the fly using | |||

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meta_programming meta programming] | |||

|- | |||

| Difficult to include one algorithm under several strategies | |||

| Unbounded [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymorphism_in_object-oriented_programming polymorphism]/Mixins makes one algorithm reusable | |||

under several strategies | |||

|- | |||

| Difficult to evaluate new algorithms inside strategies | |||

| New algorithms can be evaluated dynamically using <code>eval</code> | |||

|- | |||

| Syntactic regular expression support not available. | |||

| Interesting algorithm use cases can be constructed using the | |||

syntactic [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regular_expression regular expression] support for Ruby | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

== Where Ruby wins? == | == Where Ruby wins? == | ||

= References = | |||

== See Also == | The comparison yields interesting insights into the advantages of Ruby over Java. Clearly Ruby has much higher edge in using OO design patterns like strategy over any other statically typed language. | ||

# Ruby's code is succinct, Java requires more boilerplate code due to the static nature of the language | |||

# Closures make it trivial to add parameters to the strategy implementations, in Java parameters to strategies must be instance or class variables | |||

# Unbounded polymorphism/[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mixins mixins] of Ruby provides better code reusability | |||

# Highly dynamic strategies can be constructed using meta programming features of Ruby | |||

# New algorithms can be evaluated dynamically with ease | |||

= References = | |||

===Books=== | |||

#[http://www.amazon.com/Programming-Ruby-Pragmatic-Programmers-Second/dp/0974514055 Programming Ruby: The programmatic programmer’s guide] | |||

#[http://www.amazon.com/Head-First-Design-Patterns/dp/0596007124 Head First Design Patterns] | |||

===Links=== | |||

#[http://www.dofactory.com/Patterns/PatternStrategy.aspx Strategy Pattern - Data and Object Factory] | |||

#[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Design_pattern_(computer_science) Design Patterns - Wikipedia] | |||

#[http://www.javaworld.com/javaworld/jw-04-2002/jw-0426-designpatterns.html Strategy for Success - Java World] | |||

===See Also=== | |||

#[http://davidhayden.com/blog/dave/archive/2005/07/01/1875.aspx Strategy Design Pattern and Open-Closed Principle] | |||

#[http://www.devshed.com/c/a/PHP/Introducing-the-Strategy-Pattern/ Strategy Pattern for PHP Explained] | |||

''Note: Santthosh (sbselvad@ncsu.edu) and Agustin (agusvega@nc.rr.com) edited this page.'' | |||

Latest revision as of 01:15, 11 October 2007

The Strategy Design Pattern, comparing a dynamic OO language to a static OO language

In this page we explore the differences in implementation and design of the Strategy design pattern between the dynamic Object-Oriented language Ruby and the static Object-Oriented language Java.

Definitions

Design Patterns

A design pattern is a general repeatable solution to a commonly occurring problem in software design. A design pattern is neither a finished design nor a solution that can be transformed directly into code. It is a template on how to solve a problem that can be used in many different situations. Design patterns are more often use in Object-oriented designs as they typically show relationships and interactions between classes or objects, without specifying the final application classes or objects that are involved.

Note: Algorithms are not design patterns, algorithms solve computational problems and design patterns solve design problems.

Strategy Pattern

The Strategy Design Pattern defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each one, and makes them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it.

The Strategy pattern lets one build software as a loosely coupled collection of interchangeable parts, in contrast to a monolithic, tightly coupled system. That loose coupling makes the software much more extensible, maintainable, and reusable. The strategy pattern is useful for situations where it is necessary to dynamically swap the algorithms used in an application.

Structure

Normally there are 3 types of classes and or objects that participate in a strategy pattern implementation

- Strategy

- declares an interface common to all supported algorithms. Context uses this interface to call the algorithm defined by a ConcreteStrategy

- ConcreteStrategy

- implements the algorithm using the Strategy interface

- Context

- is configured with a ConcreteStrategy object

- maintains a reference to a Strategy object

- may define an interface that lets Strategy access its data.

For example lets take the general case of sorting a list. One may wish to use different sort strategies based on the length of the list as performance of these sort algorithms vary depending on the size of the list. Here SortStrategy will be the common interface to all supported sort algorithms (like QuickSort, MergeSort, Bubble Sort etc.,) and SortedList will be the context that lets Strategy access the list and operate on it.

Merits

- A family of algorithms can be defined as a class hierarchy and can be used interchangeably to alter application behavior without changing its architecture.

- By encapsulating the algorithm separately, new algorithms complying with the same interface can be easily introduced.

- The application can switch strategies at run-time.

- Strategy enables the clients to choose the required algorithm, without using a "switch" statement or a series of "if-else" statements.

- Data structures used for implementing the algorithm are completely encapsulated in Strategy classes. Therefore, the implementation of an algorithm can be changed without affecting the Context class.

- Strategy Pattern can be used instead of sub-classing the Context class. Inheritance hardwires the behavior with the Context and the behavior cannot be changed dynamically.

- The same Strategy object can be strategically shared between different Context objects. However, the shared Strategy object should not maintain states across invocations.

Demerits

Note: Most of these demerits are specific to statically typed languages like Java. Use of dynamic object oriented languages like Ruby can help bypass these demerits

- The application must be aware of all the strategies to select the right one for the right situation.

- Context and the Strategy classes normally communicate through the interface specified by the abstract Strategy base class. Strategy base class must expose interface for all the required behaviors, which some concrete Strategy classes might not implement.

- In most cases, the application configures the Context with the required Strategy object. Therefore, the application needs to create and maintain two objects in place of one.

- Since, the Strategy object is created by the application in most cases; the Context has no control on lifetime of the Strategy object. However, the Context can make a local copy of the Strategy object. But, this increases the memory requirement and has a sure performance impact.

Related Patterns

Command and Bridge are two closely related patterns to Strategy.

- A Command pattern encapsulates a single action, therefore it tends to have a single method with a rather generic signature. It often is intended to be stored for a longer time and to be executed later. Strategy, in contrast, is used to customize an algorithm. A strategy might have a number of methods specific to the algorithm. Most often strategies will be instantiated immediately before executing the algorithm, and discarded afterwards.

- Bridge pattern is meant for structure, whereas the Strategy pattern is meant for behavior. The coupling between the context and the strategies is tighter than the coupling between the abstraction and the implementation in the Bridge pattern.

Alternatives

In some programming languages, such as those without polymorphism, the issues addressed by strategy pattern are handled through forms of reflection, such as the native function pointer or function delegate syntax.

Real World Case Study

To demonstrate further let us consider an application that manages songs and playlists, and helps you copy/synchronize songs to you compact MP3 player or Mobile phone. The application accepts a playlist which has a catalog of MP3 files in different directories.

Let critical actions performed on the files in playlist be renaming, copying or reencoding. Let each file to be copied/synchronized be represented by a FileJob object instance containing the source and destination paths. The actual action (rename/copy/reencode) that needs to be performed is given to the FileJob object as an instance of a class implementing the FileOperation interface. The application then has three different file operations: CopyOperation, RenameOperation and ReencodeOperation. Therefore, FileJob is the context class, the FileOperation interface is the strategy, and CopyOperation, RenameOperation and ReencodeOperation are concrete strategies.

Java's Solution

Here is the Java implementation of the playlist synchronization application.

import java.util.ArrayList;

// This is the Strategy interface

interface FileOperation {

public void Run(String from, String to);

}

// These are the three different implementations

class CopyOperation implements FileOperation {

public void Run(String from, String to) {

System.out.println("Copy " + from + " to " + to + ".");

}

}

class ReencodeOperation implements FileOperation {

private int bitRate_; // In kbps

ReencodeOperation(int bitRate) {

bitRate_ = bitRate;

}

public void Run(String from, String to) {

System.out.println("Reencode " + from + " to " + to + " at " + bitRate_ + "kbps.");

}

}

class RenameOperation implements FileOperation {

public void Run(String from, String to) {

System.out.println("Rename " + from + " to " + to + ".");

}

}

// This is the context class

class FileJob {

String from_;

String to_;

FileOperation op_;

public FileJob(String from, String to, FileOperation op) {

from_ = from;

to_ = to;

op_ = op;

}

void Run() {

op_.Run(from_, to_);

}

}

// Sample code

class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ArrayList<FileJob> jobs = new ArrayList<FileJob>();

FileOperation copyOp = new CopyOperation();

FileOperation renameOp = new RenameOperation();

FileOperation reencodeOp = new ReencodeOperation(128); // kbps

jobs.add(new FileJob("file1", "file2", copyOp));

jobs.add(new FileJob("file3", "file4", renameOp));

jobs.add(new FileJob("file5", "file6", reencodeOp));

for (FileJob j : jobs) {

j.Run();

}

}

}

Ruby's Solution

Here is the Ruby implementation of the playlist synchronization application.

# To give the file operation invocation a better name we define an alias, note

# that this is optional, one can just use 'call', but it is better to adapt

# the name to the problem domain

class FileOperation < Proc

alias_method :run, :call

end

# These are the strategies

copyOp = FileOperation.new { |from, to| puts "Copy #{from} to #{to}." }

renameOp = FileOperation.new { |from, to| puts "Rename #{from} to #{to}." }

bitRate = 128 # kbps

reencodeOp = FileOperation.new { |from, to| puts "Reencode #{from} to #{to} at #{bitRate}kbps." }

# This is the context class

class FileJob

def initialize(from, to, op)

@from = from

@to = to

@op = op

end

def run

@op.run(@from, @to)

end

end

# The same test as the Java implementation

jobs = Array.new

jobs << FileJob.new("file1", "file2", copyOp);

jobs << FileJob.new("file3", "file4", renameOp);

jobs << FileJob.new("file5", "file6", reencodeOp);

jobs.each { |j| j.run() }

Java versus Ruby

Comparison

Let us perform a comparison to better understand the implementation

| Java's Strategy Implementation | Ruby's Strategy Implementation |

|---|---|

| An interface declaration, defines a common interface to the

algorithm family |

No interface declaration required |

| A class is required for each strategy implementation | No classes required, closures are good enough |

| Algorithms for strategies need to be defined at compile time | New algorithms for strategies can be created on the fly using |

| Difficult to include one algorithm under several strategies | Unbounded polymorphism/Mixins makes one algorithm reusable

under several strategies |

| Difficult to evaluate new algorithms inside strategies | New algorithms can be evaluated dynamically using eval

|

| Syntactic regular expression support not available. | Interesting algorithm use cases can be constructed using the

syntactic regular expression support for Ruby |

Where Ruby wins?

The comparison yields interesting insights into the advantages of Ruby over Java. Clearly Ruby has much higher edge in using OO design patterns like strategy over any other statically typed language.

- Ruby's code is succinct, Java requires more boilerplate code due to the static nature of the language

- Closures make it trivial to add parameters to the strategy implementations, in Java parameters to strategies must be instance or class variables

- Unbounded polymorphism/mixins of Ruby provides better code reusability

- Highly dynamic strategies can be constructed using meta programming features of Ruby

- New algorithms can be evaluated dynamically with ease

References

Books

Links

- Strategy Pattern - Data and Object Factory

- Design Patterns - Wikipedia

- Strategy for Success - Java World

See Also

Note: Santthosh (sbselvad@ncsu.edu) and Agustin (agusvega@nc.rr.com) edited this page.