CSC/ECE 506 Spring 2011/ch9 ms: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (25 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

Synchronizations are characterized by three parts: acquire, wait, and release. Both hardware and operating system synchronization rely on atomic instructions for acquire and release, but the implementations for the wait portion of a synchronization can vary. Hardware implementations usually use busy-waiting, where a process repeatedly tests a variable waiting for it to change. The operating system can wait using blocking, where the process suspends itself until woken up by another process. | Synchronizations are characterized by three parts: acquire, wait, and release. Both hardware and operating system synchronization rely on atomic instructions for acquire and release, but the implementations for the wait portion of a synchronization can vary. Hardware implementations usually use busy-waiting, where a process repeatedly tests a variable waiting for it to change. The operating system can wait using blocking, where the process suspends itself until woken up by another process. | ||

Blocking has the advantage of freeing up the processor for use by other processes, but requires operating system functions to work and thus has a lot of overhead. Busy-waiting has much less overhead, but uses processor and cache resources while waiting. Because of these tradeoffs, it is usually better to use busy-waiting for short wait periods, and blocking for long wait periods. [ | Blocking has the advantage of freeing up the processor for use by other processes, but requires operating system functions to work and thus has a lot of overhead. Busy-waiting has much less overhead, but uses processor and cache resources while waiting. Because of these tradeoffs, it is usually better to use busy-waiting for short wait periods, and blocking for long wait periods.<sup><span id="1body">[[#1foot|[1]]]</span></sup> | ||

= Lock Implementations = | = Lock Implementations = | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

*Traffic - How much bus traffic is generated by threads attempting to acquire the lock? | *Traffic - How much bus traffic is generated by threads attempting to acquire the lock? | ||

*Fairness - FIFO vs. Luck | *Fairness - FIFO vs. Luck | ||

*Storage - How much storage is needed compared to the number of threads? | *Storage - How much storage is needed compared to the number of threads?<sup><span id="2body">[[#2foot|[2]]]</span></sup> | ||

=== Acquisition Latency === | === Acquisition Latency === | ||

We want a low acquisition latency, especially for applications that repeatedly acquire and release locks. Over the run time of a program, the acquisition latency compounded many times could have a large performance affect. However, low acquisition latency has to be balanced against other factors when implementing a lock.[ | We want a low acquisition latency, especially for applications that repeatedly acquire and release locks. Over the run time of a program, the acquisition latency compounded many times could have a large performance affect. However, low acquisition latency has to be balanced against other factors when implementing a lock.<sup><span id="1body">[[#1foot|[1]]]</span></sup> | ||

=== Traffic === | === Traffic === | ||

Traffic is an important consideration when evaluating lock performance. If acquiring lock causes a lot of bus traffic, it will not scale well as the number of threads increases. Eventually the bus will become choked.[ | Traffic is an important consideration when evaluating lock performance. If acquiring lock causes a lot of bus traffic, it will not scale well as the number of threads increases. Eventually the bus will become choked.<sup><span id="1body">[[#1foot|[1]]]</span></sup> | ||

=== Fairness === | === Fairness === | ||

In general, threads should acquire a lock in them same order that the locks were requested. If this does not happen, as the number of threads increases so does the chance that a thread will become starved. [ | In general, threads should acquire a lock in them same order that the locks were requested. If this does not happen, as the number of threads increases so does the chance that a thread will become starved.<sup><span id="1body">[[#1foot|[1]]]</span></sup> | ||

=== Storage === | === Storage === | ||

The amount of storage needed per lock should be small enough such that it scales to a large number of threads without any problems. If a large amount of storage is required, then multiple threads could cause locks to consume too much memory.[ | The amount of storage needed per lock should be small enough such that it scales to a large number of threads without any problems. If a large amount of storage is required, then multiple threads could cause locks to consume too much memory.<sup><span id="1body">[[#1foot|[1]]]</span></sup> | ||

=== Performance Comparison === | === Performance Comparison === | ||

Two common lock implementations are test&set and test and test&set. In terms of performance, both have a low storage cost (scalable) and are not fair. | Two common lock implementations are test&set and test and test&set. In terms of performance, both have a low storage cost (scalable) and are not fair. Test&set has a low acquisition latency but is not scalable due do high bus traffic when there is a lot of contention for the lock. Test-and-test&set has a higher acquisition latency but scales better because it generates less bus traffic. The next figure shows performance comparisons for these two lock implementations.<sup><span id="1body">[[#1foot|[1]]]</span></sup> | ||

[[Image:lockperf.png|frame|none|Performance comparison of test&set and test-and-test&set (spin on read)<sup><span id="3body">[[#3foot|[3]]]</span></sup>]] | |||

=== Improving performance === | |||

Optimizing software can improve the performance of locks. For instance, inserting a delay between a processor noticing a release and then trying to acquire a lock can reduce contention and bus traffic, and increase the performance of the locks. TCP-like back off algorithms can be used to adjust this delay depending on the number of threads contending for the lock.<sup><span>[[#3foot|[3]]]</span></sup> | |||

Another way to improve performance is to insert a delay between memory references so as to limit the bandwidth (traffic) each processor can use for spinning.<sup><span>[[#3foot|[3]]]</span></sup> | |||

One way to guarantee fairness is to queue lock attempts in shared memory so that they happen in order.<sup><span>[[#3foot|[3]]]</span></sup> | |||

== Atomic Instructions == | == Atomic Instructions == | ||

Since a multiprocessor system cannot disable interrupts as an effective method to execute | Since a multiprocessor system cannot disable interrupts as an effective method to execute code atomically, there must be hardware support for atomic operations.<sup><span id="4body">[[#4foot|[4]]]</span></sup> | ||

The ability to execute an atomic instruction is a requirement for most lock implementations. It is important that when a processor attempts to set a lock, either the lock is fully set and the thread is able to enter into the critical section, or the lock is not set and it appears that none of the instructions required to set the lock have executed. | |||

In the x86 instruction set the opcode CMPXCHG ( | In the x86 instruction set the opcode CMPXCHG (compare and exchange) can be used in a lock implementation in order to guarantee atomicity. This function works by sending a destination and a source. The accumulator is compared to the destination and, if they are equal, loaded with the source. If they are not equal the accumulator is loaded with the destination value. In order to assure that this is executed atomically the opcode must be issued with the LOCK prefix. This is useful in implementing some locks, such as ticket locks.<sup><span id="5body">[[#5foot|[5]]]</span></sup> | ||

== Hand-off Lock == | == Hand-off Lock == | ||

Another type of lock that is not discussed in the text is known as the " | Another type of lock that is not discussed in the text is known as the "hand-off" lock. In this lock the first thread acquires the lock if no other thread is currently locked (since it is the first thread). When another thread attempts to gain the lock it will see that the lock is in use and adds itself to the queue. Once done this thread can sleep until called by the thread with the lock. Once the thread in the lock is finished, it will pass the lock to the next thread in the queue.<sup><span id="6body">[[#6foot|[6]]]</span></sup> | ||

== Avoiding Locks == | == Avoiding Locks == | ||

There are many reasons why a programmer should attempt to write programs in such a way as to avoid locks if possible. There are many problems that can arise with the use of locks. [ | There are many reasons why a programmer should attempt to write programs in such a way as to avoid locks if possible. There are many problems that can arise with the use of locks.<sup><span id="4body">[[#4foot|[4]]]</span></sup> | ||

One of the must well known | One of the must well known issues is deadlock. This can occur when the threads are waiting to acquire the lock, but the lock will never be unlocked. For example if 2 threads are both spinning on a lock that is locked, they will continue to spin forever, as each thread 'thinks' that the other is inside the critical section. | ||

Another problem with using locks is that the performance is not optimal, as often a lock is used when there is only a chance of conflict. This approach to programming yields slower performance than what might be possible with other methods. This also leads to questions of granularity, that is how much of the code should be protected under the critical section. The programmer must decide between many small (fine grain) locks or fewer, more encompassing locks. This decision can greatly effect the performance of the program. | Another problem with using locks is that the performance is not optimal, as often a lock is used when there is only a chance of conflict. This approach to programming yields slower performance than what might be possible with other methods. This also leads to questions of granularity, that is how much of the code should be protected under the critical section. The programmer must decide between many small (fine grain) locks or fewer, more encompassing locks. This decision can greatly effect the performance of the program.<sup><span id="4body">[[#4foot|[4]]]</span></sup> | ||

= Barrier Implementations = | = Barrier Implementations = | ||

| Line 67: | Line 74: | ||

*Latency - The time required to enter and exit a barrier. | *Latency - The time required to enter and exit a barrier. | ||

*Traffic - Communications overhead required by the barrier.[ | *Traffic - Communications overhead required by the barrier.<sup><span id="2body">[[#2foot|[2]]]</span></sup> | ||

=== Latency === | === Latency === | ||

Ideally the latency of a barrier should be small, but for barriers that don't scale well latency can increase as the number of threads increases. [ | Ideally the latency of a barrier should be small, but for barriers that don't scale well latency can increase as the number of threads increases.<sup><span id="1body">[[#1foot|[1]]]</span></sup> | ||

=== Traffic === | === Traffic === | ||

Low traffic is also good, as we do not want excess buss traffic to prevent scalability. [ | Low traffic is also good, as we do not want excess buss traffic to prevent scalability.<sup><span id="1body">[[#1foot|[1]]]</span></sup> | ||

=== Performance Comparison === | === Performance Comparison === | ||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" | |||

|+Performance Comparison of Barrier Implementations<sup><span id="2body">[[#2foot|[2]]]</span></sup> | |||

|- | |||

! Criteria | |||

! Sense Reversal | |||

Centralized Barrier | |||

! Combining Tree | |||

Barrier | |||

! Barrier Network | |||

(Hardware) | |||

|- | |||

| Latency | |||

| O(1) | |||

| O(log p) | |||

| O(log p) | |||

|- | |||

| Traffic | |||

| O(p<sup>2</sup>) | |||

| O(p) | |||

| moved to a separate network | |||

|} | |||

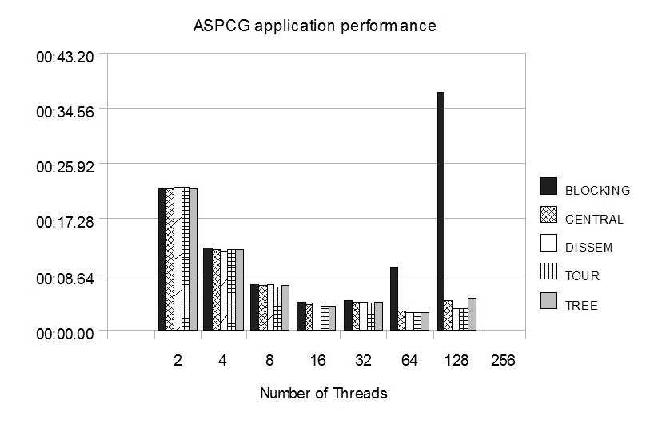

[[Image:Ch9wiki05.png|frame|none|Additive Schwarz Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient (ASPCG) kernel on Altix System - This figure shows the timings of the ASPCG kernel using the different barrier implementations. It can be seen that the blocking barrier does not scale with number of threads as with increase in number of threads the contention increases.<sup><span id="7body">[[#7foot|[7]]]</span></sup>]] | |||

[[Image:Ch9wiki06.png|frame|none|EPCC Microbenchmark - This figure shows the timings to implement a barrier of the EPCC Microbenchmark using the different barrier implementations. It can be seen that the blocking barrier/centralized blocking barrier does not scale with number of threads as with increase in number of threads the contention increases.<sup><span id="7body">[[#7foot|[7]]]</span></sup>]] | |||

== Sense-Reversal Barrier == | == Sense-Reversal Barrier == | ||

| Line 101: | Line 121: | ||

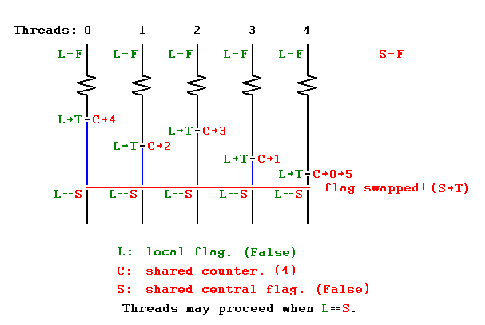

Since all the threads are spinning around a single variable the miss rate is scales quadratically with number of processors. | Since all the threads are spinning around a single variable the miss rate is scales quadratically with number of processors. | ||

[[Image:Ch9wiki01.png]] | [[Image:Ch9wiki01.png]]<sup><span id="8body">[[#8foot|[8]]]</span></sup> | ||

[ | |||

== Combining Tree Barrier == | == Combining Tree Barrier == | ||

| Line 112: | Line 131: | ||

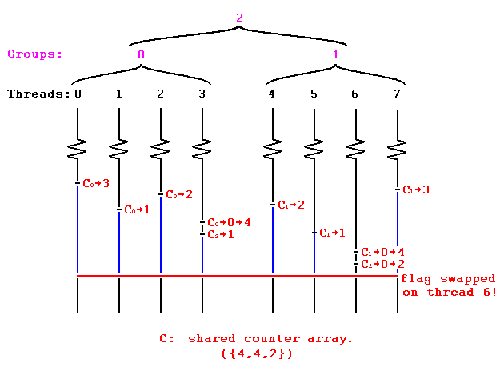

The diagram below shows the operation of combining tree barrier with threads grouped in two groups. The variables C0 and C1 are local to each group and C2 is the variable that is at higher level of hierarchy in the tree. | The diagram below shows the operation of combining tree barrier with threads grouped in two groups. The variables C0 and C1 are local to each group and C2 is the variable that is at higher level of hierarchy in the tree. | ||

[[Image:Ch9wiki02.png]] | [[Image:Ch9wiki02.png]]<sup><span id="8body">[[#8foot|[8]]]</span></sup> | ||

[ | |||

== Tournament Barrier == | == Tournament Barrier == | ||

| Line 119: | Line 137: | ||

In tournament barrier the threads are considered to be leaves at the end of a binary tree and each node represents a flag. Two threads compete with each other and the loser thread is allowed to set the flag and move to higher level and compete to lose with the loser thread from other section of binary tree. Thus the thread which completes last is able to set the highest flag in the binary tree. On setting the flag it indicates to all the threads that barrier has been completed and thus synchronization is achieved. | In tournament barrier the threads are considered to be leaves at the end of a binary tree and each node represents a flag. Two threads compete with each other and the loser thread is allowed to set the flag and move to higher level and compete to lose with the loser thread from other section of binary tree. Thus the thread which completes last is able to set the highest flag in the binary tree. On setting the flag it indicates to all the threads that barrier has been completed and thus synchronization is achieved. | ||

[[Image:Ch9wiki03.png]] | [[Image:Ch9wiki03.png]]<sup><span id="8body">[[#8foot|[8]]]</span></sup> | ||

[ | |||

== Disseminating Barrier == | == Disseminating Barrier == | ||

| Line 126: | Line 143: | ||

In this barrier each thread maintains a record of the activity of other threads. For every round i with n threads, thread A notifies thread (A + 2i) mod n. Thus after logn rounds all the threads are aware of the status of every other thread running and whether it has reached the barrier. | In this barrier each thread maintains a record of the activity of other threads. For every round i with n threads, thread A notifies thread (A + 2i) mod n. Thus after logn rounds all the threads are aware of the status of every other thread running and whether it has reached the barrier. | ||

[[Image:Ch9wiki04.png]] | [[Image:Ch9wiki04.png]]<sup><span id="9body">[[#9foot|[9]]]</span></sup> | ||

[ | |||

= References = | = References = | ||

<span id="1foot">[[#1body|1.]]</span> David Culler, J.P. Singh and Anoop Gupta. Parallel Computer Architecture: A Hardware/Software Approach. Morgan Kaufmann. August 1998.<br> | |||

<span id="2foot">[[#2body|2.]]</span> Yan Solihin. Fundamentals of Parallel Computer Architecture: Multichip and Multicore Systems. Solihin Books. August 2009.<br> | |||

<span id="3foot">[[#3body|3.]]</span> Thomas E. Anderson. The Performance of Spin Lock Alternatives for Shared-memory Multiprocessors. http://www.cc.gatech.edu/classes/AY2010/cs4210_fall/papers/anderson-spinlock.pdf<br> | |||

<span id="4foot">[[#4body|4.]]</span> http://www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Lock-(computer-science)<br> | |||

<span id="5foot">[[#5body|5.]]</span> http://faydoc.tripod.com/cpu/cmpxchg.htm<br> | |||

<span id="6foot">[[#6body|6.]]</span> http://www.cs.duke.edu/courses/fall09/cps110/slides/threads3.ppt<br> | |||

<span id="7foot">[[#7body|7.]]</span> Scalability evaluation of barrier algorithms for OpenMP. http://www2.cs.uh.edu/~hpctools/pub/iwomp-barrier.pdf<br> | |||

<span id="8foot">[[#8body|8.]]</span> Carwyn Ball and Mark Bull. Barrier Synchronization in Java. http://www.ukhec.ac.uk/publications/reports/synch_java.pdf<br> | |||

<span id="9foot">[[#9body|9.]]</span> http://www.cs.brown.edu/courses/cs176/barrier.ppt<br> | |||

Latest revision as of 03:53, 2 May 2011

Synchronization

In addition to a proper cache coherency model, it is important for a multiprocessor system to provide support for synchronization. This must be provided at the hardware level, and can also be implemented to some degree in software. The most common types of hardware synchronization are locks and barriers, which are discussed in this chapter.

Hardware vs. Operating System Synchronization

Synchronizations are characterized by three parts: acquire, wait, and release. Both hardware and operating system synchronization rely on atomic instructions for acquire and release, but the implementations for the wait portion of a synchronization can vary. Hardware implementations usually use busy-waiting, where a process repeatedly tests a variable waiting for it to change. The operating system can wait using blocking, where the process suspends itself until woken up by another process.

Blocking has the advantage of freeing up the processor for use by other processes, but requires operating system functions to work and thus has a lot of overhead. Busy-waiting has much less overhead, but uses processor and cache resources while waiting. Because of these tradeoffs, it is usually better to use busy-waiting for short wait periods, and blocking for long wait periods.[1]

Lock Implementations

Locks are an important concept when programming for multiprocessor systems. The purpose of a lock is to protect the code inside the lock, known as a critical section. It must be certain that while some thread X has entered the critical section, another thread Y is not also inside of the critical section and possibly modifying critical values. While thread X has entered the critical section, thread Y must wait until X has exited before entering. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways of varying complexity and performance.

Performance Evaluation

To evaluate lock performance, we can use these four criteria:

- Acquisition Latency - How much time does it take to acquire the lock?

- Traffic - How much bus traffic is generated by threads attempting to acquire the lock?

- Fairness - FIFO vs. Luck

- Storage - How much storage is needed compared to the number of threads?[2]

Acquisition Latency

We want a low acquisition latency, especially for applications that repeatedly acquire and release locks. Over the run time of a program, the acquisition latency compounded many times could have a large performance affect. However, low acquisition latency has to be balanced against other factors when implementing a lock.[1]

Traffic

Traffic is an important consideration when evaluating lock performance. If acquiring lock causes a lot of bus traffic, it will not scale well as the number of threads increases. Eventually the bus will become choked.[1]

Fairness

In general, threads should acquire a lock in them same order that the locks were requested. If this does not happen, as the number of threads increases so does the chance that a thread will become starved.[1]

Storage

The amount of storage needed per lock should be small enough such that it scales to a large number of threads without any problems. If a large amount of storage is required, then multiple threads could cause locks to consume too much memory.[1]

Performance Comparison

Two common lock implementations are test&set and test and test&set. In terms of performance, both have a low storage cost (scalable) and are not fair. Test&set has a low acquisition latency but is not scalable due do high bus traffic when there is a lot of contention for the lock. Test-and-test&set has a higher acquisition latency but scales better because it generates less bus traffic. The next figure shows performance comparisons for these two lock implementations.[1]

Improving performance

Optimizing software can improve the performance of locks. For instance, inserting a delay between a processor noticing a release and then trying to acquire a lock can reduce contention and bus traffic, and increase the performance of the locks. TCP-like back off algorithms can be used to adjust this delay depending on the number of threads contending for the lock.[3]

Another way to improve performance is to insert a delay between memory references so as to limit the bandwidth (traffic) each processor can use for spinning.[3]

One way to guarantee fairness is to queue lock attempts in shared memory so that they happen in order.[3]

Atomic Instructions

Since a multiprocessor system cannot disable interrupts as an effective method to execute code atomically, there must be hardware support for atomic operations.[4]

The ability to execute an atomic instruction is a requirement for most lock implementations. It is important that when a processor attempts to set a lock, either the lock is fully set and the thread is able to enter into the critical section, or the lock is not set and it appears that none of the instructions required to set the lock have executed.

In the x86 instruction set the opcode CMPXCHG (compare and exchange) can be used in a lock implementation in order to guarantee atomicity. This function works by sending a destination and a source. The accumulator is compared to the destination and, if they are equal, loaded with the source. If they are not equal the accumulator is loaded with the destination value. In order to assure that this is executed atomically the opcode must be issued with the LOCK prefix. This is useful in implementing some locks, such as ticket locks.[5]

Hand-off Lock

Another type of lock that is not discussed in the text is known as the "hand-off" lock. In this lock the first thread acquires the lock if no other thread is currently locked (since it is the first thread). When another thread attempts to gain the lock it will see that the lock is in use and adds itself to the queue. Once done this thread can sleep until called by the thread with the lock. Once the thread in the lock is finished, it will pass the lock to the next thread in the queue.[6]

Avoiding Locks

There are many reasons why a programmer should attempt to write programs in such a way as to avoid locks if possible. There are many problems that can arise with the use of locks.[4]

One of the must well known issues is deadlock. This can occur when the threads are waiting to acquire the lock, but the lock will never be unlocked. For example if 2 threads are both spinning on a lock that is locked, they will continue to spin forever, as each thread 'thinks' that the other is inside the critical section.

Another problem with using locks is that the performance is not optimal, as often a lock is used when there is only a chance of conflict. This approach to programming yields slower performance than what might be possible with other methods. This also leads to questions of granularity, that is how much of the code should be protected under the critical section. The programmer must decide between many small (fine grain) locks or fewer, more encompassing locks. This decision can greatly effect the performance of the program.[4]

Barrier Implementations

In many ways, barriers are simpler than locks. A barrier is simply a point in a program where one or more threads must reach before the parallel program is allowed to continue. When using barriers, a programmer does not have to be concerned with advanced topics such as fairness, that are required when programming for locks.

Performance Evaluation

To evaluate lock performance, we can use these two criteria:

- Latency - The time required to enter and exit a barrier.

- Traffic - Communications overhead required by the barrier.[2]

Latency

Ideally the latency of a barrier should be small, but for barriers that don't scale well latency can increase as the number of threads increases.[1]

Traffic

Low traffic is also good, as we do not want excess buss traffic to prevent scalability.[1]

Performance Comparison

| Criteria | Sense Reversal

Centralized Barrier |

Combining Tree

Barrier |

Barrier Network

(Hardware) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latency | O(1) | O(log p) | O(log p) |

| Traffic | O(p2) | O(p) | moved to a separate network |

Sense-Reversal Barrier

This barrier is a centralized barrier where a single count variable protected by a lock is shared among all the threads. Each thread on reaching the barrier increments its value and waits till the value of variable has reached the number of threads for which barrier was implemented.

Since all the threads are spinning around a single variable the miss rate is scales quadratically with number of processors.

Combining Tree Barrier

This barrier is a distributed barrier where group of processors form clusters and updates value of a local variable. The local variable on reaching a value equal to number of threads updating it, proceeds to increment another variable higher in hierarchy in the combining tree. When the variable in the highest level of hierarchy in the combining tree reaches its max value it is considered that all the threads have reached the barrier and synchronization is complete.

Since in this case all the threads are updated local variables in form of smaller groups the miss rate is not as high as sense-reversal barrier.

The diagram below shows the operation of combining tree barrier with threads grouped in two groups. The variables C0 and C1 are local to each group and C2 is the variable that is at higher level of hierarchy in the tree.

Tournament Barrier

In tournament barrier the threads are considered to be leaves at the end of a binary tree and each node represents a flag. Two threads compete with each other and the loser thread is allowed to set the flag and move to higher level and compete to lose with the loser thread from other section of binary tree. Thus the thread which completes last is able to set the highest flag in the binary tree. On setting the flag it indicates to all the threads that barrier has been completed and thus synchronization is achieved.

Disseminating Barrier

In this barrier each thread maintains a record of the activity of other threads. For every round i with n threads, thread A notifies thread (A + 2i) mod n. Thus after logn rounds all the threads are aware of the status of every other thread running and whether it has reached the barrier.

References

1. David Culler, J.P. Singh and Anoop Gupta. Parallel Computer Architecture: A Hardware/Software Approach. Morgan Kaufmann. August 1998.

2. Yan Solihin. Fundamentals of Parallel Computer Architecture: Multichip and Multicore Systems. Solihin Books. August 2009.

3. Thomas E. Anderson. The Performance of Spin Lock Alternatives for Shared-memory Multiprocessors. http://www.cc.gatech.edu/classes/AY2010/cs4210_fall/papers/anderson-spinlock.pdf

4. http://www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Lock-(computer-science)

5. http://faydoc.tripod.com/cpu/cmpxchg.htm

6. http://www.cs.duke.edu/courses/fall09/cps110/slides/threads3.ppt

7. Scalability evaluation of barrier algorithms for OpenMP. http://www2.cs.uh.edu/~hpctools/pub/iwomp-barrier.pdf

8. Carwyn Ball and Mark Bull. Barrier Synchronization in Java. http://www.ukhec.ac.uk/publications/reports/synch_java.pdf

9. http://www.cs.brown.edu/courses/cs176/barrier.ppt