CSC/ECE 517 Fall 2010/ch1 1f TU: Difference between revisions

| (411 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Some of the benefits are: | Some of the benefits are: | ||

* Proof of your code | * Proof of your code. | ||

* Better design - Thinking about the tests can help us to create small design elements, thereby improving the modularity and reusability of units. | * Better design - Thinking about the tests can help us to create small design elements, thereby improving the modularity and reusability of units. | ||

* Safety net on bugs - Unit tests will confirm that while refactoring no additional errors were introduced. | * Safety net on bugs - Unit tests will confirm that while refactoring no additional errors were introduced. | ||

* | * Relative cost - It helps to detect and remove defects in a more cost effective manner compared to the other stages of testing. | ||

* | * Individual tests - Enables us to test parts of a source code in isolation. | ||

* | * Less compile-build-debug cycles - Makes debugging more efficient by searching for bugs in the probable code areas. | ||

* Documentation - Designers can look at the unit test for a particular method and learn about its functionality. | * Documentation - Designers can look at the unit test for a particular method and learn about its functionality. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Unit Test Framework is a software tool to support writing and running unit test. | Unit Test Framework is a software tool to support writing and running unit test. | ||

= | [[Image:wiki_fig1.png|450x450px|<span title="Figure 1.1"></span>]] | ||

' | The above diagram shows the relationships of unit tests to production code. Application is built from objects linked together. The unit test uses this application's objects but exists inside the unit test framework. | ||

This is a | == A few words == | ||

Before we jump into the next two frameworks let us clarify a few terms. | |||

=== Test Driven Development === | |||

In this approach at first we write a unit test for a function without writing the code for the function. This test will definitely fail because the function is not present. Now we can add just about enough code to our function and again run the test suite to make it pass. If it fails we can change our code to make it pass. By sticking to this approach we can write efficient and flawless codes. | |||

=== Behaviour Driven Development === | |||

BDD preserves the basic iterative (fail-pass) workflow of TDD, but stresses on specifying behaviors that are understandable to people (say from non programming background). In this approach we write tests in a natural language such that even a non programmer can understand. Also, BDD lets you look at the code implementation from a behavioral abstraction perspective. So now we can say "A recipe can't be created without specifying the description" rather than writing something like Test_category_ThrowsArgumentNullException. It makes more sense from readability perspective. | |||

== List of most popular unit testing frameworks for Ruby == | |||

* [http://pg-server.csc.ncsu.edu/mediawiki/index.php/CSC/ECE_517_Fall_2010/ch1_1f_TU#Test::Unit Test::Unit] | |||

* [http://pg-server.csc.ncsu.edu/mediawiki/index.php/CSC/ECE_517_Fall_2010/ch1_1f_TU#Shoulda Shoulda] | |||

* [http://pg-server.csc.ncsu.edu/mediawiki/index.php/CSC/ECE_517_Fall_2010/ch1_1f_TU#RSpec RSpec] | |||

* [http://pg-server.csc.ncsu.edu/mediawiki/index.php/CSC/ECE_517_Fall_2010/ch1_1f_TU#Cucumber Cucumber] | |||

'''Simple application code in Ruby''' | |||

Let us write a Calculator class in a file called calculator.rb. It has four methods addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Later in the chapter we shall write tests in each of the above frameworks respectively. | |||

class Calculator | class Calculator | ||

| Line 59: | Line 73: | ||

end | end | ||

end | end | ||

=== Test::Unit === | === Test::Unit === | ||

==== Features of Test::Unit ==== | ==== Features of Test::Unit ==== | ||

;''' TestCase ''' | |||

::::Test::Unit's most elemental class is TestCase, the base class for a unit test. All unit tests are inherited from TestCase. | |||

;''' Assertions ''' | |||

::::An assertion statement specifies a condition that you expect to hold true at some particular point in your program. If that condition does not hold true, the assertion fails. An error is propagated with pertinent information so that you can go back and make your assertion succeed. To gain further knowledge about various Test::Unit assertions, we recommend going through the module [http://ruby-doc.org/stdlib/libdoc/test/unit/rdoc/classes/Test/Unit/Assertions.html Test::Unit::Assertions] | |||

;''' Test Fixture ''' | |||

::::A test fixture is used to initialize (and cleanup) the common objects for two or more tests. It eliminates unnecessary duplication. | |||

;''' Test Method ''' | |||

::::A test method is a definitive procedure that produces a test result. | |||

;''' Test Runners ''' | |||

::::To run the test cases and report the results, we need a Test Runner. Examples -Test::Unit::UI::Console::TestRunner, Test::Unit::UI::GTK::TestRunner, etc. | |||

;''' Test Suite ''' | |||

::::A collection of tests which can be run. | |||

==== Installing Test::Unit ==== | |||

All Ruby versions comes preinstalled with Test::Unit framework. | |||

==== Usage ==== | ==== Usage ==== | ||

At first you write a test method. Within that test, you use assertions to test whether conditions are correct in each situation. The results of a run are gathered in a test result and displayed to the user through some UI. To write a test, follow these steps: | |||

* Require ‘test/unit’ and set your test class to inherit from Test::Unit::TestCase. | |||

* Write methods prefixed with "test". | |||

* Assert things you decide should be true. | |||

* Optionally define setup and/or teardown to set up and/or tear down your common test fixture. | |||

* Run your tests as Test::Unit Test and fix the bugs until everything passes. | |||

===== Example of a test class ===== | |||

<pre> | |||

require "calculator" | require "calculator" | ||

require "test/unit" | require "test/unit" | ||

class TC_Calculator < Test::Unit::TestCase | class TC_Calculator < Test::Unit::TestCase | ||

| Line 85: | Line 142: | ||

end | end | ||

end | end | ||

</pre> | |||

If we run it | If we run this test, here is how it'll look like - | ||

[[Image:testui.jpg|900x1000px]] | |||

=== Shoulda === | === Shoulda === | ||

==== Features of Shoulda ==== | ==== Features of Shoulda ==== | ||

* It allows to write | * It is a library that allows us to write better and more understandable tests for your Ruby application. | ||

* It allows to | * It's like overdrive for Test::Unit and RSpec. | ||

* It | * It allows us to set up contexts which equal the describe-blocks in RSpec. The context framework helps us avoid the tedious method-based style of Test::Unit. | ||

* It allows us to use the "it"-blocks from RSpec to define nice error-messages if a test fails. | |||

* Shoulda is simply an extension to Test::Unit. It works inside Test::Unit — you can even mix Shoulda tests with regular Test::Unit test methods. | |||

* Shoulda consists of [http://rdoc.info/github/thoughtbot/shoulda/master/file/README.rdoc matchers, test helpers, and assertions] (which we'll not be covering in this Chapter). | |||

==== Installing Shoulda ==== | |||

If your Environment path is set to " ...\Ruby\bin" then open command prompt and run gem install shoulda. | |||

==== Usage ==== | ==== Usage ==== | ||

So here is our class "TC_Calculator_Shoulda" which inherits "Test::Unit::TestCase". | |||

* Add require"rubygems" and require "shoulda" to the script. | |||

* Set up a context (context is nothing but a region of code you're interested in.) | |||

* Define a method starting with should “...” do and give a description to the method. | |||

* Make assertions in your method. | |||

<pre> | |||

require "rubygems" | require "rubygems" | ||

require "calculator" | require "calculator" | ||

require "test/unit" | require "test/unit" | ||

require "shoulda" | require "shoulda" | ||

class TC_Calculator_Shoulda < Test::Unit::TestCase | class TC_Calculator_Shoulda < Test::Unit::TestCase | ||

context "Calculate" do | context "Calculate" do | ||

should "addition of two numbers " do | should "addition of two numbers " do | ||

assert_equal 8,Calculator.new(3,4).addition | assert_equal 8,Calculator.new(3,4).addition | ||

end | end | ||

should "subtraction of two numbers " do | should "subtraction of two numbers " do | ||

assert_equal 1,Calculator.new(4,3).subtraction | assert_equal 1,Calculator.new(4,3).subtraction | ||

end | end | ||

should "multiplication of two numbers" do | should "multiplication of two numbers" do | ||

assert_equal 12,Calculator.new(3,4).multiplication | assert_equal 12,Calculator.new(3,4).multiplication | ||

end | end | ||

should "division of two numbers" do | should "division of two numbers" do | ||

assert_equal 4,Calculator.new(12,3).division | assert_equal 4,Calculator.new(12,3).division | ||

end | end | ||

end | end | ||

end | end | ||

</pre> | |||

Let us run it as a "Ruby Application": | |||

''produces: | |||

Loaded suite tc__calculator__shoulda | Loaded suite tc__calculator__shoulda | ||

| Line 143: | Line 215: | ||

<7>. | <7>. | ||

4 tests, 4 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors | 4 tests, 4 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors | ||

=== RSpec === | |||

===== Features of RSpec ===== | |||

* RSpec is a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behaviour-driven_development Behavior Driven Development] tool for ruby. | |||

* It provides [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain-specific_language Domain-specific language] for talking about what code should do (allows developers to write system requirements in a Ruby format). | |||

* An evolution from [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Test-driven_development Test-driven development] and Domain Driven Design. | |||

* The RSpec framework provides us a way to write [http://pg-server.csc.ncsu.edu/mediawiki/index.php/CSC/ECE_517_Fall_2010/ch1_1f_TU#Initial_spec specifications] for our code that are executable well before you’ve written a line of application code. | |||

* These specs take us a step ahead of shoulda's nice and descriptive error messages. When run, these specs will output the system requirements that describe your application. | |||

Too much theory up front can be dangerous, right? Let us jump into working with RSpec. We'll cover some of the basic RSpec concepts along the way. When it'll be time for us to point out yet another feature, we'll start the line with an asterisk (*) - Bullet list. | |||

==== Installing RSpec ==== | |||

If your Environment path is set to " ...\Ruby\bin" then open command prompt and run gem install rspec. | |||

==== Usage ==== | |||

===== Initial spec ===== | |||

You start by describing what your application, method or class should behave like. Let us create our first specification file: | |||

require "calculator" | |||

describe "TheCalculator's", "basic calculating" do <span style="color:green;"># * The describe() method returns an ExampleGroup class (similar to TestCase in Test::Unit)</span> | |||

it "should add two numbers correctly" do <span style="color:green;"># * The it() method returns an instance of the ExampleGroup in which that example is run.</span> | |||

it "should subtract two numbers correctly" do | |||

it "should multiply two numbers correctly" do | |||

it "should divide two numbers correctly" do | |||

#... | |||

end | |||

What do we have here? First, at line 2 we defined a context for our test, using RSpec's describe block. Furthermore we have four behaviors/expectations (it "should ..." -blocks), defining what we expect our system to behave like (expectations are similar to assertions in Test::Unit framework). | |||

* There are contexts (describe) with examples, before and after blocks. Specs are made up of contexts that contain expectations in the form of examples. | |||

* There are two methods available for checking expectations: should() and should_not(). Spec::Expectations - Object#should(matcher) and Object#should_not(matcher). | |||

We can run this specification using the spec command: | |||

$ spec unit_test.rb | |||

''produces'': | |||

<pre> | |||

**** | |||

Pending: | |||

TheCalculator's basic calculating should add two numbers correctly (Not Yet Impl | |||

emented) | |||

./21file.rb:5 | |||

TheCalculator's basic calculating should subtract two numbers correctly (Not Yet | |||

Implemented) | |||

./21file.rb:7 | |||

TheCalculator's basic calculating should multiply two numbers correctly (Not Yet | |||

Implemented) | |||

./21file.rb:9 | |||

TheCalculator's basic calculating should divide two numbers correctly (Not Yet I | |||

mplemented) | |||

./21file.rb:11 | |||

Finished in 0.021001 seconds | |||

4 examples, 0 failures, 4 pending | |||

</pre> | |||

* Examples can be pending. | |||

===== Establishing behavior ===== | |||

Isn't it cool? Executing the tests echoes our expectations back at us, telling us that each has yet to be implemented. This is forcing/establishing behavior. We know that all calculator's must perform the above functions. We don't know how we're going to design this yet, but the tests will derive our design. | |||

* RSpec drives the design. | |||

===== Writing the application code ===== | |||

At the very end, you write the application code, and fire up the tests to check, if it behaves the way you wanted while writing the tests… but we're getting ahead of ourself. | |||

===== Developing the code ===== | |||

Let's go a step further and associate code blocks with our expectations. | |||

<pre> | |||

require "calculator" | |||

describe "TheCalculator's", "basic calculating" do | |||

before(:each) do | |||

@cal = Calculator.new(6,2) | |||

end | |||

it "should add two numbers correctly" do | |||

@cal.addition.should == 8 | |||

end | |||

it "should subtract two numbers correctly" do | |||

@cal.subtraction.should == 4 | |||

end | |||

it "should multiply two numbers correctly" do | |||

@cal.multiplication.should == 11 | |||

end | |||

it "should divide two numbers correctly" do | |||

@cal.division.should == 3 | |||

end | |||

end | |||

</pre> | |||

Note that creating a Calculator object for each of our expectations would have created duplication in the specification. This can be fixed using the hook before :each. This does exactly what it sounds like it does. It is called before each example is executed, allowing you to set up initial state for your specs. | |||

Let us run it: | |||

''produces:'' | |||

<pre> | |||

Spec::Expectations::ExpectationNotMetError: | |||

expected: 11, | |||

got: 12 (using ==) | |||

./unit_test.rb:17 | |||

</pre> | |||

Uh-oh! The third expectation did not meet. See how the error message uses the fact that the expectation knows both the expected and actual values. | |||

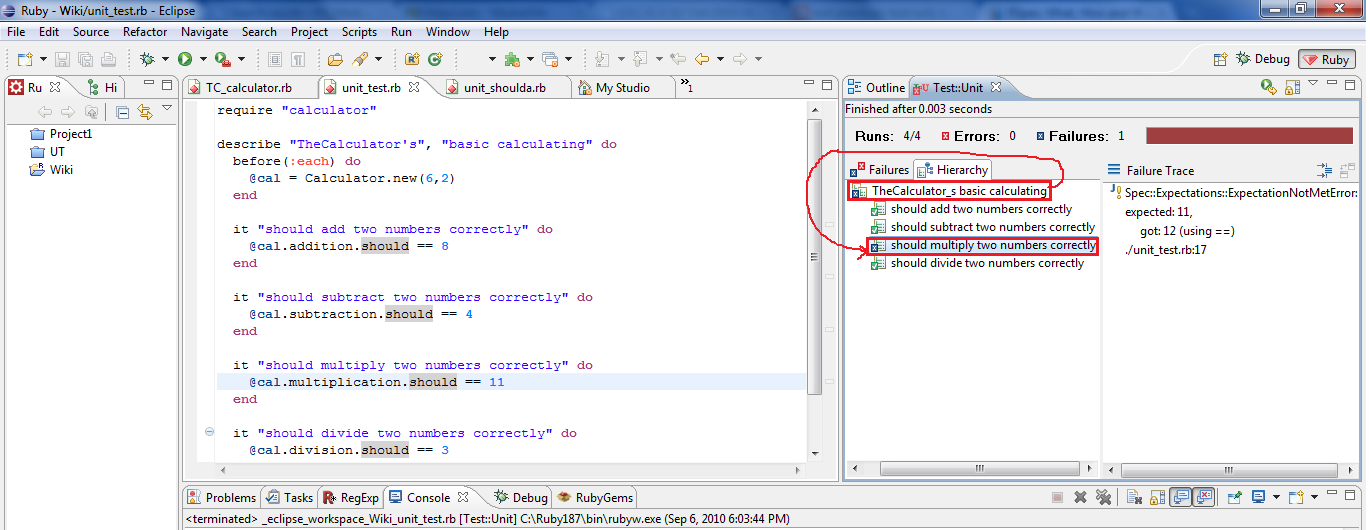

In eclipse RSpec will generate a nice description text for you when an expectation is not met. | |||

[[Image:Rspe.png|900x1000px]] | |||

=== Cucumber === | |||

Cucumber is fast becoming the standard for acceptance testing framework. | |||

==== Features of Cucumber ==== | |||

* Its a Behavior Driven Development(BDD) tool for Ruby. | |||

* It allows the features of a system to be written in the native language of the program as either specs or functional tests. | |||

* It follows GWT(Given,When,Then) pattern. | |||

* Cucumber itself is written in Ruby. | |||

==== Installing Cucumber ==== | |||

If your Environment path is set to " ...\Ruby\bin" then open command prompt and run gem install cucumber. | |||

==== Usage ==== | |||

Let us first create a feature file to describe about our requirements.Feature defines a functionality of the system. | |||

<pre> | |||

Feature: Addition | |||

In order perform addition of two numbers | |||

As a user | |||

I want the sum of two numbers | |||

Scenario: Add two numbers | |||

Given I have entered <input1> | |||

And I have entered <input2> | |||

When I give add | |||

Then The result should be <output> | |||

</pre> | |||

Then we will create a ruby file to give a code implementation | |||

<pre> | |||

require 'calculator' | |||

Before do | |||

@input1=3 | |||

@input2=4 | |||

end | |||

Given /^I have entered <input(\d+)>$/ do |arg1| | |||

@calc = Calculator.new(@input1,@input2) | |||

end | |||

When /^I give add$/ do | |||

@result = @calc.addition | |||

end | |||

Then /^The result should be <output>$/ do | |||

puts @result | |||

end | |||

</pre> | |||

Now if we run the feature file we will get the following | |||

<pre> | |||

Feature: Addition | |||

In order perform addition of two numbers | |||

As a user | |||

I want the sum of two numbers | |||

Scenario: Add two numbers # calculator.feature:7 | |||

Given I have entered <input1> # addition.rb:8 | |||

And I have entered <input2> # addition.rb:8 | |||

When I give add # addition.rb:12 | |||

7 | |||

Then The result should be <output> # addition.rb:16 | |||

1 scenario (1 passed) | |||

4 steps (4 passed) | |||

0m0.010s | |||

</pre> | |||

== Comparison of Test::Unit, Shoulda, RSpec == | |||

<br> | |||

{|cellspacing="0" border="1" | |||

!style="width:33%"|Test::Unit | |||

!style="width:33%"|Shoulda | |||

!style="width:33%"|RSpec | |||

|- | |||

| <p align="justify">Test::Unit is a testing framework provided by Ruby. It is based on Test Driven Development.</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">Shoulda is an extension to Test::Unit. It is basically Test::Unit with more capabilities and simpler readable syntax.</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">RSpec is a Behavior Driven Development framework provided by Ruby. Its an evolution from TDD and Domain Driven Design.</p> | |||

|- | |||

| <p align="justify">Test::Unit provides assertions, test methods, test fixtures, test runners and test suites.</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">Shoulda provide macros, helpers, matchers</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">RSpec provides a Domain Specific Language to express the behavior of code. Basically RSpec is TDD embraced with documentation.</p> | |||

|- | |||

| <p align="justify">Test::Unit does not allow nested setup and nested teardown though multiple setup methods and teardown methods are provided in Test::Unit 2x.0.</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">Shoulda allows nested contexts which helps to create different environment for different set of tests.</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">RSpec allows nested describe structure.</p> | |||

|- | |||

| <p align="justify">There is a certain opaqueness to Test::Unit that requires you to know more about the framework to make use of it. What we mean by this is that here we end up writing a whole bunch of low level code instead of being able to say in a English like language.</p> | |||

|<p align="justify">Shoulda provides more descriptive method names compared to Test::Unit. It avoid tedious naming conventions of Test::Unit.</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">RSpec is clearly far more expressive (designed more for human readability). Specifications are more documenting and communicate better than tests.</p> | |||

|- | |||

| <p align="justify">Test::Unit is the base library.</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">Shoulda applies a patch to the TestCase class to provide the added features.</p> | |||

| <p align="justify">RSpec goes even further and applies a patch to the object class. It gives us a should method.</p> | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

<br> | |||

== Conclusion == | |||

<br> | |||

We like RSpec best since we enjoy its readability most. We love the pending keyword, which allows us to set up the tests to be written later on. It helps to focus on exactly one test and one failure. Shoulda would be our second choice because the tests are just as readable as RSpec, even if the output takes some learning to read. | |||

=== Comparison of run times === | |||

The following are the run times for these three frameworks testing the same calculator class with 4 succesful tests - | |||

'''RSpec''' | |||

:::::Finished in 0.023002 seconds | |||

:::::4 examples, 0 failures | |||

'''Shoulda''' | |||

:::::Finished in 0.002 seconds. | |||

:::::4 tests, 4 assertions, 0 failures, 0 errors | |||

'''Test::unit''' | |||

:::::Finished in 0.001 seconds. | |||

:::::4 tests, 4 assertions, 0 failures, 0 errors | |||

[[Image:Graph.jpg|500x500px]] | |||

We see from the above diagram that while RSpec provides a wide variety of features, but they come to us at a cost. RSpec has several thousand lines of Ruby. Often this is much larger than the software that’s being tested. This size makes RSpec quite a bit slower than other testing frameworks, and a lot harder to learn in its entirety. Though benchmarking testing frameworks on the basis of execution time is not such a good idea. | |||

= External Links = | |||

*[http://ruby-doc.org/stdlib/libdoc/test/unit/rdoc/classes/Test/Unit.html] Test::Unit<br> | |||

*[http://ruby-doc.org/stdlib/libdoc/test/unit/rdoc/] Ruby-doc <br> | |||

*[http://rdoc.info/github/thoughtbot/shoulda/master/file/README.rdoc] Shoulda<br> | |||

*[http://rspec.info/] RSpec<br> | |||

*[http://rspec.info/documentation/] RSpec Documentation<br> | |||

*[http://github.com/thoughtbot/shoulda] Shoulda<br> | |||

*[http://cukes.info/] Cucumber <br> | |||

*[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unit_testing] Unit testing<br> | |||

*[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Test-driven_development] Test-driven development<br> | |||

= References = | |||

* R.Venkat Rajendran, [http://www.mobilein.com/WhitePaperonUnitTesting.pdf ''White Paper on Unit Testing''] | |||

* Dave Thomas, with Chad Fowler and Andy Hunt [http://pragprog.com/titles/ruby/programming-ruby ''Programing Ruby''], The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC, 2005 | |||

* Paul Hamill [http://oreilly.com/catalog/9780596006891 ''Unit Test Frameworks''], O'Reilly Media, 2004 | |||

Latest revision as of 23:47, 20 September 2010

Unit-testing frameworks for Ruby

Unit Testing

A unit is the smallest building block of a software. Such a unit can be: a class, a method, an interface etc. Unit testing is the process of validating such units of code.

Benefits

Some of the benefits are:

- Proof of your code.

- Better design - Thinking about the tests can help us to create small design elements, thereby improving the modularity and reusability of units.

- Safety net on bugs - Unit tests will confirm that while refactoring no additional errors were introduced.

- Relative cost - It helps to detect and remove defects in a more cost effective manner compared to the other stages of testing.

- Individual tests - Enables us to test parts of a source code in isolation.

- Less compile-build-debug cycles - Makes debugging more efficient by searching for bugs in the probable code areas.

- Documentation - Designers can look at the unit test for a particular method and learn about its functionality.

Unit-testing frameworks

Unit Test Framework is a software tool to support writing and running unit test.

The above diagram shows the relationships of unit tests to production code. Application is built from objects linked together. The unit test uses this application's objects but exists inside the unit test framework.

A few words

Before we jump into the next two frameworks let us clarify a few terms.

Test Driven Development

In this approach at first we write a unit test for a function without writing the code for the function. This test will definitely fail because the function is not present. Now we can add just about enough code to our function and again run the test suite to make it pass. If it fails we can change our code to make it pass. By sticking to this approach we can write efficient and flawless codes.

Behaviour Driven Development

BDD preserves the basic iterative (fail-pass) workflow of TDD, but stresses on specifying behaviors that are understandable to people (say from non programming background). In this approach we write tests in a natural language such that even a non programmer can understand. Also, BDD lets you look at the code implementation from a behavioral abstraction perspective. So now we can say "A recipe can't be created without specifying the description" rather than writing something like Test_category_ThrowsArgumentNullException. It makes more sense from readability perspective.

List of most popular unit testing frameworks for Ruby

Simple application code in Ruby

Let us write a Calculator class in a file called calculator.rb. It has four methods addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Later in the chapter we shall write tests in each of the above frameworks respectively.

class Calculator

attr_writer :number1

attr_writer :number2

def initialize(number1,number2)

@number1 = number1

@number2 = number2

end

#-----------Addition of two numbers----------------#

def addition

result = @number1 + @number2

return result

end

#----------Subtraction of two numbers--------------#

def subtraction

result= @number1 - @number2

return result

end

#----------Multiplication of two numbers------------#

def multiplication

result= @number1 * @number2

return result

end

#-----------Division of two numbers-------------------#

def division

result = @number1 / @number2

return result

end

end

Test::Unit

Features of Test::Unit

- TestCase

- Test::Unit's most elemental class is TestCase, the base class for a unit test. All unit tests are inherited from TestCase.

- Assertions

- An assertion statement specifies a condition that you expect to hold true at some particular point in your program. If that condition does not hold true, the assertion fails. An error is propagated with pertinent information so that you can go back and make your assertion succeed. To gain further knowledge about various Test::Unit assertions, we recommend going through the module Test::Unit::Assertions

- Test Fixture

- A test fixture is used to initialize (and cleanup) the common objects for two or more tests. It eliminates unnecessary duplication.

- Test Method

- A test method is a definitive procedure that produces a test result.

- Test Runners

- To run the test cases and report the results, we need a Test Runner. Examples -Test::Unit::UI::Console::TestRunner, Test::Unit::UI::GTK::TestRunner, etc.

- Test Suite

- A collection of tests which can be run.

Installing Test::Unit

All Ruby versions comes preinstalled with Test::Unit framework.

Usage

At first you write a test method. Within that test, you use assertions to test whether conditions are correct in each situation. The results of a run are gathered in a test result and displayed to the user through some UI. To write a test, follow these steps:

- Require ‘test/unit’ and set your test class to inherit from Test::Unit::TestCase.

- Write methods prefixed with "test".

- Assert things you decide should be true.

- Optionally define setup and/or teardown to set up and/or tear down your common test fixture.

- Run your tests as Test::Unit Test and fix the bugs until everything passes.

Example of a test class

require "calculator"

require "test/unit"

class TC_Calculator < Test::Unit::TestCase

def test_addition

assert_equal(8,Calculator.new(3,4).addition)

end

def test_subtraction

assert_same(1,Calculator.new(4,3).subtraction)

end

def test_multiplication

assert_not_same(12,Calculator.new(3,4).multiplication)

end

def test_division

assert_not_equal(5,Calculator.new(8,2).division)

end

end

If we run this test, here is how it'll look like -

Shoulda

Features of Shoulda

- It is a library that allows us to write better and more understandable tests for your Ruby application.

- It's like overdrive for Test::Unit and RSpec.

- It allows us to set up contexts which equal the describe-blocks in RSpec. The context framework helps us avoid the tedious method-based style of Test::Unit.

- It allows us to use the "it"-blocks from RSpec to define nice error-messages if a test fails.

- Shoulda is simply an extension to Test::Unit. It works inside Test::Unit — you can even mix Shoulda tests with regular Test::Unit test methods.

- Shoulda consists of matchers, test helpers, and assertions (which we'll not be covering in this Chapter).

Installing Shoulda

If your Environment path is set to " ...\Ruby\bin" then open command prompt and run gem install shoulda.

Usage

So here is our class "TC_Calculator_Shoulda" which inherits "Test::Unit::TestCase".

- Add require"rubygems" and require "shoulda" to the script.

- Set up a context (context is nothing but a region of code you're interested in.)

- Define a method starting with should “...” do and give a description to the method.

- Make assertions in your method.

require "rubygems"

require "calculator"

require "test/unit"

require "shoulda"

class TC_Calculator_Shoulda < Test::Unit::TestCase

context "Calculate" do

should "addition of two numbers " do

assert_equal 8,Calculator.new(3,4).addition

end

should "subtraction of two numbers " do

assert_equal 1,Calculator.new(4,3).subtraction

end

should "multiplication of two numbers" do

assert_equal 12,Calculator.new(3,4).multiplication

end

should "division of two numbers" do

assert_equal 4,Calculator.new(12,3).division

end

end

end

Let us run it as a "Ruby Application":

produces:

Loaded suite tc__calculator__shoulda

Started

F...

Finished in 0.064 seconds.

1) Failure:

test: Calculate should addition of two numbers . (TC_Calculator_Shoulda)

<8> expected but was

<7>.

4 tests, 4 assertions, 1 failures, 0 errors

RSpec

Features of RSpec

- RSpec is a Behavior Driven Development tool for ruby.

- It provides Domain-specific language for talking about what code should do (allows developers to write system requirements in a Ruby format).

- An evolution from Test-driven development and Domain Driven Design.

- The RSpec framework provides us a way to write specifications for our code that are executable well before you’ve written a line of application code.

- These specs take us a step ahead of shoulda's nice and descriptive error messages. When run, these specs will output the system requirements that describe your application.

Too much theory up front can be dangerous, right? Let us jump into working with RSpec. We'll cover some of the basic RSpec concepts along the way. When it'll be time for us to point out yet another feature, we'll start the line with an asterisk (*) - Bullet list.

Installing RSpec

If your Environment path is set to " ...\Ruby\bin" then open command prompt and run gem install rspec.

Usage

Initial spec

You start by describing what your application, method or class should behave like. Let us create our first specification file:

require "calculator" describe "TheCalculator's", "basic calculating" do # * The describe() method returns an ExampleGroup class (similar to TestCase in Test::Unit) it "should add two numbers correctly" do # * The it() method returns an instance of the ExampleGroup in which that example is run. it "should subtract two numbers correctly" do it "should multiply two numbers correctly" do it "should divide two numbers correctly" do #... end

What do we have here? First, at line 2 we defined a context for our test, using RSpec's describe block. Furthermore we have four behaviors/expectations (it "should ..." -blocks), defining what we expect our system to behave like (expectations are similar to assertions in Test::Unit framework).

- There are contexts (describe) with examples, before and after blocks. Specs are made up of contexts that contain expectations in the form of examples.

- There are two methods available for checking expectations: should() and should_not(). Spec::Expectations - Object#should(matcher) and Object#should_not(matcher).

We can run this specification using the spec command:

$ spec unit_test.rb

produces:

**** Pending: TheCalculator's basic calculating should add two numbers correctly (Not Yet Impl emented) ./21file.rb:5 TheCalculator's basic calculating should subtract two numbers correctly (Not Yet Implemented) ./21file.rb:7 TheCalculator's basic calculating should multiply two numbers correctly (Not Yet Implemented) ./21file.rb:9 TheCalculator's basic calculating should divide two numbers correctly (Not Yet I mplemented) ./21file.rb:11 Finished in 0.021001 seconds 4 examples, 0 failures, 4 pending

- Examples can be pending.

Establishing behavior

Isn't it cool? Executing the tests echoes our expectations back at us, telling us that each has yet to be implemented. This is forcing/establishing behavior. We know that all calculator's must perform the above functions. We don't know how we're going to design this yet, but the tests will derive our design.

- RSpec drives the design.

Writing the application code

At the very end, you write the application code, and fire up the tests to check, if it behaves the way you wanted while writing the tests… but we're getting ahead of ourself.

Developing the code

Let's go a step further and associate code blocks with our expectations.

require "calculator"

describe "TheCalculator's", "basic calculating" do

before(:each) do

@cal = Calculator.new(6,2)

end

it "should add two numbers correctly" do

@cal.addition.should == 8

end

it "should subtract two numbers correctly" do

@cal.subtraction.should == 4

end

it "should multiply two numbers correctly" do

@cal.multiplication.should == 11

end

it "should divide two numbers correctly" do

@cal.division.should == 3

end

end

Note that creating a Calculator object for each of our expectations would have created duplication in the specification. This can be fixed using the hook before :each. This does exactly what it sounds like it does. It is called before each example is executed, allowing you to set up initial state for your specs.

Let us run it:

produces:

Spec::Expectations::ExpectationNotMetError:

expected: 11,

got: 12 (using ==)

./unit_test.rb:17

Uh-oh! The third expectation did not meet. See how the error message uses the fact that the expectation knows both the expected and actual values.

In eclipse RSpec will generate a nice description text for you when an expectation is not met.

Cucumber

Cucumber is fast becoming the standard for acceptance testing framework.

Features of Cucumber

- Its a Behavior Driven Development(BDD) tool for Ruby.

- It allows the features of a system to be written in the native language of the program as either specs or functional tests.

- It follows GWT(Given,When,Then) pattern.

- Cucumber itself is written in Ruby.

Installing Cucumber

If your Environment path is set to " ...\Ruby\bin" then open command prompt and run gem install cucumber.

Usage

Let us first create a feature file to describe about our requirements.Feature defines a functionality of the system.

Feature: Addition In order perform addition of two numbers As a user I want the sum of two numbers Scenario: Add two numbers Given I have entered <input1> And I have entered <input2> When I give add Then The result should be <output>

Then we will create a ruby file to give a code implementation

require 'calculator' Before do @input1=3 @input2=4 end Given /^I have entered <input(\d+)>$/ do |arg1| @calc = Calculator.new(@input1,@input2) end When /^I give add$/ do @result = @calc.addition end Then /^The result should be <output>$/ do puts @result end

Now if we run the feature file we will get the following

Feature: Addition

In order perform addition of two numbers

As a user

I want the sum of two numbers

Scenario: Add two numbers # calculator.feature:7

Given I have entered <input1> # addition.rb:8

And I have entered <input2> # addition.rb:8

When I give add # addition.rb:12

7

Then The result should be <output> # addition.rb:16

1 scenario (1 passed)

4 steps (4 passed)

0m0.010s

Comparison of Test::Unit, Shoulda, RSpec

| Test::Unit | Shoulda | RSpec |

|---|---|---|

Test::Unit is a testing framework provided by Ruby. It is based on Test Driven Development. |

Shoulda is an extension to Test::Unit. It is basically Test::Unit with more capabilities and simpler readable syntax. |

RSpec is a Behavior Driven Development framework provided by Ruby. Its an evolution from TDD and Domain Driven Design. |

Test::Unit provides assertions, test methods, test fixtures, test runners and test suites. |

Shoulda provide macros, helpers, matchers |

RSpec provides a Domain Specific Language to express the behavior of code. Basically RSpec is TDD embraced with documentation. |

Test::Unit does not allow nested setup and nested teardown though multiple setup methods and teardown methods are provided in Test::Unit 2x.0. |

Shoulda allows nested contexts which helps to create different environment for different set of tests. |

RSpec allows nested describe structure. |

There is a certain opaqueness to Test::Unit that requires you to know more about the framework to make use of it. What we mean by this is that here we end up writing a whole bunch of low level code instead of being able to say in a English like language. |

Shoulda provides more descriptive method names compared to Test::Unit. It avoid tedious naming conventions of Test::Unit. |

RSpec is clearly far more expressive (designed more for human readability). Specifications are more documenting and communicate better than tests. |

Test::Unit is the base library. |

Shoulda applies a patch to the TestCase class to provide the added features. |

RSpec goes even further and applies a patch to the object class. It gives us a should method. |

Conclusion

We like RSpec best since we enjoy its readability most. We love the pending keyword, which allows us to set up the tests to be written later on. It helps to focus on exactly one test and one failure. Shoulda would be our second choice because the tests are just as readable as RSpec, even if the output takes some learning to read.

Comparison of run times

The following are the run times for these three frameworks testing the same calculator class with 4 succesful tests -

RSpec

- Finished in 0.023002 seconds

- 4 examples, 0 failures

Shoulda

- Finished in 0.002 seconds.

- 4 tests, 4 assertions, 0 failures, 0 errors

Test::unit

- Finished in 0.001 seconds.

- 4 tests, 4 assertions, 0 failures, 0 errors

We see from the above diagram that while RSpec provides a wide variety of features, but they come to us at a cost. RSpec has several thousand lines of Ruby. Often this is much larger than the software that’s being tested. This size makes RSpec quite a bit slower than other testing frameworks, and a lot harder to learn in its entirety. Though benchmarking testing frameworks on the basis of execution time is not such a good idea.

External Links

- [1] Test::Unit

- [2] Ruby-doc

- [3] Shoulda

- [4] RSpec

- [5] RSpec Documentation

- [6] Shoulda

- [7] Cucumber

- [8] Unit testing

- [9] Test-driven development

References

- R.Venkat Rajendran, White Paper on Unit Testing

- Dave Thomas, with Chad Fowler and Andy Hunt Programing Ruby, The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC, 2005

- Paul Hamill Unit Test Frameworks, O'Reilly Media, 2004