CSC/ECE 517 Fall 2009/wiki3 17 VR: Difference between revisions

| (34 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font size=4>Single choice principle'''</font> | '''<font size=4>Single choice principle'''</font> | ||

<br>Bertrand Meyer is the author of the book, "Object Oriented Software Construction", which is considered a foundational text of object-oriented programming book. In this book, he has mentioned about the five principles which explain modularity requirements. This wiki will explore through the Single Choice Principle in particular and its usage. | <br>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bertrand_Meyer Bertrand Meyer]is the author of the book, "Object Oriented Software Construction<sup>[1]</sup>", which is considered a foundational text of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Object-oriented_programming object-oriented programming] book. In this book, he has mentioned about the five principles which explain [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Module_%28programming%29 modularity] requirements. This wiki will explore through the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single_choice_principle Single Choice Principle] in particular and its usage. | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

In 1978, Yourdon and Constantine defined a software module as “a lexically contiguous sequence of program statements, bounded by boundary elements, having an aggregate identifier.” They had also proposed two important techniques namely – | In 1978, Yourdon and Constantine defined a software module as<sup>[2]</sup> “a lexically contiguous sequence of program statements, bounded by boundary elements, having an aggregate identifier.” They had also proposed two important techniques namely – “[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coupling_%28computer_science%29 Coupling]” and “[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cohesion_%28computer_science%29 Cohesion]” for measuring the dependability between modules. | ||

The various '''fundamental requirements''' resulting from a "modular" design method are : | The various '''fundamental requirements''' resulting from a "modular" design method are : | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li>'''DECOMPOSABILITY'''<br> | <li>'''DECOMPOSABILITY'''<br> | ||

Meyer defined decomposability as : | Meyer defined decomposability as :<sup>[1]</sup> | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

" A software construction method satisfies Modular Decomposability if : | " A software construction method satisfies Modular Decomposability if : | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

independent enough to allow further work to proceed separately on each of them." | independent enough to allow further work to proceed separately on each of them." | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

[[Image:Criteria1-decomposability.JPG]] | [[Image:Criteria1-decomposability.JPG|frame|center| http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf]] | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li>'''COMPOSABILITY''' | <li>'''COMPOSABILITY'''<br> | ||

Meyer defined composability as : | Meyer defined composability as :<sup>[1]</sup> | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

A method satisfies Modular Composability if it favors the production of | A method satisfies Modular Composability if it favors the production of software elements which may then be freely combined with each other to | ||

software elements which may then be freely combined with each other to | produce new systems, possibly in an environment quite different from the one in which they were initially developed. | ||

produce new systems, possibly in an environment quite different from the | |||

one in which they were initially developed. | |||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

<br>[[Image:Criteria2-composability.JPG]]</li> | <br>[[Image:Criteria2-composability.JPG|frame|center| http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf]]</li> | ||

<li>'''UNDERSTANDABILITY''' | <li>'''UNDERSTANDABILITY''' | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Meyer defined understandability as : | Meyer defined understandability as :<sup>[1]</sup> | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

A method favors Modular Understandability if it helps produce software in | A method favors Modular Understandability if it helps produce software in which a human reader can understand each module without having to | ||

which a human reader can understand each module without having to know | know the others, or, at worst, by having to examine only a few of the others. | ||

the others, or, at worst, by having to examine only a few of the others. | |||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

[[Image:Criteria3-understandability.JPG]]</li> | [[Image:Criteria3-understandability.JPG|frame|center| http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf]]</li> | ||

<li>'''CONTINUITY''' | <li>'''CONTINUITY''' | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Meyer defined Continuity as :<sup>[1]</sup> | |||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

A method satisfies Modular Continuity if, in the software architectures that | A method satisfies Modular Continuity if, in the software architectures that it yields, a small change in a problem specification will trigger | ||

it yields, a small change in a problem specification will trigger a change of | a change of just one module, or a small number of modules. | ||

just one module, or a small number of modules. | |||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

[[Image:Criteria4-continuity.JPG]]</li> | [[Image:Criteria4-continuity.JPG|frame|center| http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf]]</li> | ||

<li>'''PROTECTION''' | <li>'''PROTECTION''' | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Meyer defined Protection as:<sup>[1]</sup> | |||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

A method satisfies Modular Protection if it yields architectures in which the | A method satisfies Modular Protection if it yields architectures in which the effect of an abnormal condition occurring at run time in a | ||

effect of an abnormal condition occurring at run time in a module will remain | module will remain confined to that module, or at worst will only propagate to a few neighboring modules. | ||

confined to that module, or at worst will only propagate to a few neighboring | |||

modules. | |||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

[[Image:Criteria5-protection.JPG]]</li> | [[Image:Criteria5-protection.JPG|frame|center| http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf]]</li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

In order to ensure modularity the following five rules must be followed: | In order to ensure modularity the following five rules<sup>[1]</sup> must be followed: | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li>Direct mapping</li> | <li>Direct mapping: | ||

<li>Small interfaces(weak coupling)</li> | </li> | ||

<li>Explicit interfaces</li> | <li>Small interfaces(weak coupling): | ||

<li>Information Hiding</li> | </li> | ||

<li>Few interfaces</li> | <li>Explicit interfaces: | ||

</li> | |||

<li>[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_hiding Information Hiding]: | |||

</li> | |||

<li>Few interfaces: | |||

</li> | |||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

There are five principles of software construction which are to be followed along with the above stated requirements and rules. They are: | There are five principles<sup>[1]</sup> of software construction which are to be followed along with the above stated requirements and rules. They are: | ||

<table width=100%> | <table width=100%> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 122: | Line 123: | ||

== In detail == | == In detail == | ||

This principle is a | The single choice principle is a principle of [http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Computer_Programming/Imperative_programming imperative computer programming]. This principle is a particular case of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don%27t_repeat_yourself Don't repeat yourself principle(DRY)]. | ||

It was defined by Bertrand Meyer as: | |||

<pre> "Whenever a software system must support a set of alternatives, one and only one module in the system should know their exhaustive list."</pre><sup>[1] </sup> | |||

The definition stated above talks about an exhaustive list. | |||

OO systems handle this by having a class hierarchy<sub>[4]</sub>. | |||

For example: old style procedural code to print different "shape" objects can be written as follows: | |||

<pre> | |||

if (type==CIRCLE) | |||

print "Circle with r=" + radius; | |||

else if (type==Square) | |||

print "Square with sides=" + sideLength; | |||

else if (type==Rectangle) | |||

print "Rectangle with height=" + height + ", width=" + width; | |||

endif | |||

</pre> | |||

But there is a possibility that the same list of choices can be used for computing the area and rendering it to a GUI and checking if the parameters are overlapping with any other shape. | |||

So, instead of having a list of cases which must be modified in all places, whenever we need to add a shape, we can use the concept of subclasses. | |||

<i>NOTE: This supports the Open-Closed Principle also. </i> | |||

Let us extend the above case a bit more in detail - <b>Object oriented example</b> : | |||

<pre> | |||

class Circle inherits Shape { | |||

method scale {....} | |||

method rotate {....} | |||

method draw {....} | |||

} | |||

class Rectangle inherits Shape { | |||

method scale {....} | |||

method rotate {....} | |||

method draw {....} | |||

} | |||

class Polygon inherits Shape { | |||

method scale {....} | |||

method rotate {....} | |||

method draw {....} | |||

} | |||

</pre> | |||

The operations used in the three classes are scale, rotate and draw. These methods have been repeated in all the three classes. | |||

If a new method, for e.g., fillup() needs to be added, then, it must be added in all the three shapes and then the code becomes: | |||

<pre> | |||

class Circle inherits Shape { | |||

method scale {....} | |||

method rotate {....} | |||

method draw {....} | |||

method fillup {....} // NEW METHOD | |||

} | |||

class Rectangle inherits Shape { | |||

method scale {....} | |||

method rotate {....} | |||

method draw {....} | |||

method fillup {....} // NEW METHOD | |||

} | |||

class Polygon inherits Shape { | |||

method scale {....} | |||

method rotate {....} | |||

method draw {....} | |||

method fillup {....} // NEW METHOD | |||

} | |||

</pre> | |||

Hence,in the process of software evolution, a programmer must accept that there is a possibility for certain methods or variants to arise. In such a case, to support the software over long term, there must be a method for protecting the structure of the software in order to overcome such changes. | |||

Let us consider another example for better understanding. Assume <b>the case of a library management system</b>. | |||

Consider the Publications of a library. In Pascal-Ada syntax, we can represent the Publications type as follows: | |||

<pre language="ADA"> | <pre language="ADA"> | ||

type PUBLICATION = | type PUBLICATION = | ||

| Line 138: | Line 207: | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

In this representation the fields author ,title and publication_year are common to all the instances and others are specific to individual variants. | |||

Now consider a module which contains the above representative declaration and let the module be A. | |||

When A is open : | |||

fields can be added or new variants can be implemented. | |||

A must be closed when A must be enabled to have clients i.e. the listing of all fields and variants is completed now. | |||

Consider B a client of A. | |||

If B has to manipulate publications through a variable like p it can be done in the following way : | |||

<pre>p: PUBLICATION</pre> | <pre>p: PUBLICATION</pre> | ||

If we must differentiate between the various cases of p, it can be done as follows: | |||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

case p of | case p of | ||

| Line 157: | Line 230: | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

Hence, by using the case instruction, we can move choice control between variants. | |||

The major point to be noted is that this coding sequence works fine for this list of variants of publication supported by A. But later on when a new variant like technical report of university, etc. is to be added, the definition of <b>PUBLICATION</b> has to be modified to cater the need of the new case. | |||

Hence, by knowing the list of the list of choices we confine it to a module and hence prepare that module for any further changes i.e. addition of variants, editing of variants, etc. | |||

== Characteristics == | |||

Based upon the above explanation, certain characteristic conclusions of the single choice principle can be derived: | |||

<ol> | |||

<li> | |||

The <b>number of modules</b> which must know the list of choices should be <b>exactly ONE</b>. | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

This principle is about <b>distribution of knowledge</b> in a software system.In order to obtain durable system architectures strict steps must be taken to limit the amount of information that is being made available to each module. | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

< | Single choice principle is a direct consequence of <b>Open-Closed Principle</b>. | ||

< | </li> | ||

<li> | |||

< | <li> | ||

Single choice principle is also a strong form of <b>Information Hiding</b>. | |||

</li> | |||

</ol> | |||

== Few more examples == | |||

The best example of the single choice principle in practice is an object factory <sup>[6]</sup>. A [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factory_object object factory] is a class which implements behavior to construct objects. It is intended to be the single place in a system where object allocation occurs. An object factory would have to have knowledge of all of the different classes in the system, and support some means for the caller to describe the type of the object they wanted to allocate. Internally the object factory would implement a large switch/case statement that would allocate the class matching the caller's input. | |||

The following example source code illustrates the above explanation: <sup>[http://www.gamedev.net/reference/programming/features/objectfactory/ 7]</sup> | |||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

class ShapeFactory | |||

if | { | ||

public: | |||

Shape *Create(int shape) | |||

{ | |||

if (shape == SQUARE) | |||

return new Square; | |||

else if (shape == CIRCLE) | |||

return new Circle; | |||

else if (shape == TRIANGLE) | |||

return new Triangle; | |||

} | |||

}; | |||

ShapeFactory shape_factory; | |||

Shape *shape1 = shape_factory.Create(TRIANGLE); | |||

Shape *shape2 = shape_factory.Create(SQUARE); | |||

</pre> | |||

Single choice principle has been applied during the design of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eiffel_(programming_language) Eiffel]. | |||

== Conclusion == | |||

At face value the single-choice principle seems extremely logical, and in some contexts of "alternatives", it makes perfect sense. Consider an application of the command patten, where an some module supported execution of commands deriving from a generic command interface. It would probably be useful to have a list of all of the classes implementing the command interface in a single place. This could perhaps be used to pass the alternatives back to a user interface. | |||

There are some other aspects of the single-choice principle that are contentious. In the context of a list of methods being the "alternatives", O-O systems employing interfaces would require each class implementing an interface to provide an implementation of the method. In this context, the lists of alternatives, the methods, exist in multiple places. This is in contrast to how such a system might be implemented in a procedural language, where the list of alternatives might be kept in a single place, at the expense of having a massive if statement to drive the logic instead of polymorphism. | |||

Hence, this principle of single choice directs us to limit the dissemination of exhaustive knowledge about variants of certain notion. | |||

== Abbreviations == | |||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li> | <li>GUI - Graphical User Interface.</li> | ||

<li>DRY - Dont repeat yourself.</li> | |||

<li>OO - Object Oriented</li> | |||

</ul> | |||

== References == | |||

<ol> | |||

<li>Object Oriented Software Construction by Bertrand Meyer, Second Edition. | |||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li> | <li>E.Yourdon and L.Constantine. Structured Design, Prentice Hall, New Jersey 1978. | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li> | <li> | ||

Publication : Role Modelling for Component Design. Liping Zhao, Elizabeth A. Kendall | |||

</li> | </li> | ||

</ | <li> | ||

[http://74.125.95.132/search?q=cache:XYgBuKnOufoJ:c2.com/cgi/wiki%3FSingleChoicePrinciple+Single+choice+principle&cd=3&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us Single-choice principle] | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single_choice_principle Single choice principle - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia] | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

http://tedfelix.com/software/meyer1997.html | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

[http://www.gamedev.net/reference/programming/features/objectfactory/ Creating a Generic Object Factory] | |||

</li> | |||

</ol> | |||

Latest revision as of 05:02, 19 November 2009

Single choice principle

Bertrand Meyeris the author of the book, "Object Oriented Software Construction[1]", which is considered a foundational text of object-oriented programming book. In this book, he has mentioned about the five principles which explain modularity requirements. This wiki will explore through the Single Choice Principle in particular and its usage.

Introduction

In 1978, Yourdon and Constantine defined a software module as[2] “a lexically contiguous sequence of program statements, bounded by boundary elements, having an aggregate identifier.” They had also proposed two important techniques namely – “Coupling” and “Cohesion” for measuring the dependability between modules.

The various fundamental requirements resulting from a "modular" design method are :

- DECOMPOSABILITY

Meyer defined decomposability as :[1]" A software construction method satisfies Modular Decomposability if : it helps in the task of decomposing a software problem into a small number of less complex sub problems, connected by a simple structure, and independent enough to allow further work to proceed separately on each of them."

http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf - COMPOSABILITY

Meyer defined composability as :[1]A method satisfies Modular Composability if it favors the production of software elements which may then be freely combined with each other to produce new systems, possibly in an environment quite different from the one in which they were initially developed.

http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf - UNDERSTANDABILITY

Meyer defined understandability as :[1]A method favors Modular Understandability if it helps produce software in which a human reader can understand each module without having to know the others, or, at worst, by having to examine only a few of the others.

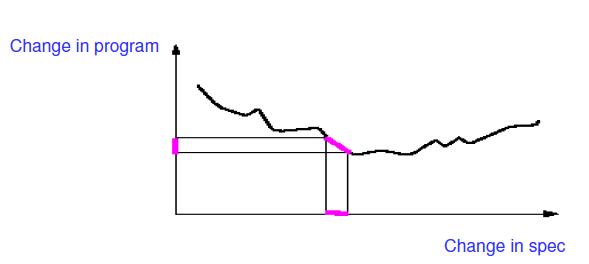

http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf - CONTINUITY

Meyer defined Continuity as :[1]A method satisfies Modular Continuity if, in the software architectures that it yields, a small change in a problem specification will trigger a change of just one module, or a small number of modules.

http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf - PROTECTION

Meyer defined Protection as:[1]A method satisfies Modular Protection if it yields architectures in which the effect of an abnormal condition occurring at run time in a module will remain confined to that module, or at worst will only propagate to a few neighboring modules.

http://mod2.fontysvenlo.org/pdffiles/M1_OOAD_Introduction.pdf

In order to ensure modularity the following five rules[1] must be followed:

- Direct mapping:

- Small interfaces(weak coupling):

- Explicit interfaces:

- Information Hiding:

- Few interfaces:

There are five principles[1] of software construction which are to be followed along with the above stated requirements and rules. They are:

| The Linguistic Modular Units principle | : |

This principle states that modules must correspond to syntactic units in the language used. |

|

|

The self-documentation principle |

: |

This principle states that the designer of a module should strive to make all information about the module part of the module itself. |

|

|

The uniform access principle |

: |

This principle states that all services offered by a module should be available through a uniform notation, which does not betray whether they are implemented through storage or through computation. |

|

|

The open-closed principle |

: |

This principle states that the modules should be both open and closed. |

|

|

The single choice principle |

: |

This principle states that whenever a software system must support a set of alternatives, one and only one module in the system should know their exhaustive list. |

In detail

The single choice principle is a principle of imperative computer programming. This principle is a particular case of the Don't repeat yourself principle(DRY).

It was defined by Bertrand Meyer as:

"Whenever a software system must support a set of alternatives, one and only one module in the system should know their exhaustive list."

[1]

The definition stated above talks about an exhaustive list. OO systems handle this by having a class hierarchy[4].

For example: old style procedural code to print different "shape" objects can be written as follows:

if (type==CIRCLE) print "Circle with r=" + radius; else if (type==Square) print "Square with sides=" + sideLength; else if (type==Rectangle) print "Rectangle with height=" + height + ", width=" + width; endif

But there is a possibility that the same list of choices can be used for computing the area and rendering it to a GUI and checking if the parameters are overlapping with any other shape.

So, instead of having a list of cases which must be modified in all places, whenever we need to add a shape, we can use the concept of subclasses. NOTE: This supports the Open-Closed Principle also.

Let us extend the above case a bit more in detail - Object oriented example :

class Circle inherits Shape {

method scale {....}

method rotate {....}

method draw {....}

}

class Rectangle inherits Shape {

method scale {....}

method rotate {....}

method draw {....}

}

class Polygon inherits Shape {

method scale {....}

method rotate {....}

method draw {....}

}

The operations used in the three classes are scale, rotate and draw. These methods have been repeated in all the three classes. If a new method, for e.g., fillup() needs to be added, then, it must be added in all the three shapes and then the code becomes:

class Circle inherits Shape {

method scale {....}

method rotate {....}

method draw {....}

method fillup {....} // NEW METHOD

}

class Rectangle inherits Shape {

method scale {....}

method rotate {....}

method draw {....}

method fillup {....} // NEW METHOD

}

class Polygon inherits Shape {

method scale {....}

method rotate {....}

method draw {....}

method fillup {....} // NEW METHOD

}

Hence,in the process of software evolution, a programmer must accept that there is a possibility for certain methods or variants to arise. In such a case, to support the software over long term, there must be a method for protecting the structure of the software in order to overcome such changes.

Let us consider another example for better understanding. Assume the case of a library management system.

Consider the Publications of a library. In Pascal-Ada syntax, we can represent the Publications type as follows:

type PUBLICATION = record author, title: STRING; publication_year: INTEGER case pubtype: (book, journal, conference_proceedings) of book: (publisher: STRING); journal: (volume, issue: STRING); proceedings: (editor, place: STRING) -- Conference proceedings end

In this representation the fields author ,title and publication_year are common to all the instances and others are specific to individual variants.

Now consider a module which contains the above representative declaration and let the module be A.

When A is open : fields can be added or new variants can be implemented.

A must be closed when A must be enabled to have clients i.e. the listing of all fields and variants is completed now.

Consider B a client of A. If B has to manipulate publications through a variable like p it can be done in the following way :

p: PUBLICATION

If we must differentiate between the various cases of p, it can be done as follows:

case p of book: ...Instructions which may access the field p l publisher... journal: ...Instructions which may access fields p l volume, pl issue... proceedings: ...Instructions which may access fields p l editor, pl place... end

Hence, by using the case instruction, we can move choice control between variants.

The major point to be noted is that this coding sequence works fine for this list of variants of publication supported by A. But later on when a new variant like technical report of university, etc. is to be added, the definition of PUBLICATION has to be modified to cater the need of the new case.

Hence, by knowing the list of the list of choices we confine it to a module and hence prepare that module for any further changes i.e. addition of variants, editing of variants, etc.

Characteristics

Based upon the above explanation, certain characteristic conclusions of the single choice principle can be derived:

- The number of modules which must know the list of choices should be exactly ONE.

- This principle is about distribution of knowledge in a software system.In order to obtain durable system architectures strict steps must be taken to limit the amount of information that is being made available to each module.

- Single choice principle is a direct consequence of Open-Closed Principle.

- Single choice principle is also a strong form of Information Hiding.

Few more examples

The best example of the single choice principle in practice is an object factory [6]. A object factory is a class which implements behavior to construct objects. It is intended to be the single place in a system where object allocation occurs. An object factory would have to have knowledge of all of the different classes in the system, and support some means for the caller to describe the type of the object they wanted to allocate. Internally the object factory would implement a large switch/case statement that would allocate the class matching the caller's input.

The following example source code illustrates the above explanation: 7

class ShapeFactory

{

public:

Shape *Create(int shape)

{

if (shape == SQUARE)

return new Square;

else if (shape == CIRCLE)

return new Circle;

else if (shape == TRIANGLE)

return new Triangle;

}

};

ShapeFactory shape_factory;

Shape *shape1 = shape_factory.Create(TRIANGLE);

Shape *shape2 = shape_factory.Create(SQUARE);

Single choice principle has been applied during the design of Eiffel.

Conclusion

At face value the single-choice principle seems extremely logical, and in some contexts of "alternatives", it makes perfect sense. Consider an application of the command patten, where an some module supported execution of commands deriving from a generic command interface. It would probably be useful to have a list of all of the classes implementing the command interface in a single place. This could perhaps be used to pass the alternatives back to a user interface.

There are some other aspects of the single-choice principle that are contentious. In the context of a list of methods being the "alternatives", O-O systems employing interfaces would require each class implementing an interface to provide an implementation of the method. In this context, the lists of alternatives, the methods, exist in multiple places. This is in contrast to how such a system might be implemented in a procedural language, where the list of alternatives might be kept in a single place, at the expense of having a massive if statement to drive the logic instead of polymorphism.

Hence, this principle of single choice directs us to limit the dissemination of exhaustive knowledge about variants of certain notion.

Abbreviations

- GUI - Graphical User Interface.

- DRY - Dont repeat yourself.

- OO - Object Oriented

References

- Object Oriented Software Construction by Bertrand Meyer, Second Edition.

- E.Yourdon and L.Constantine. Structured Design, Prentice Hall, New Jersey 1978.

- Publication : Role Modelling for Component Design. Liping Zhao, Elizabeth A. Kendall

- Single-choice principle

- Single choice principle - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- http://tedfelix.com/software/meyer1997.html

- Creating a Generic Object Factory