CSC/ECE 506 Spring 2011/ch12 ob: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

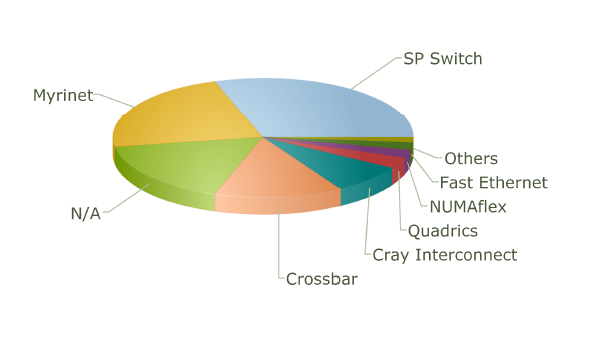

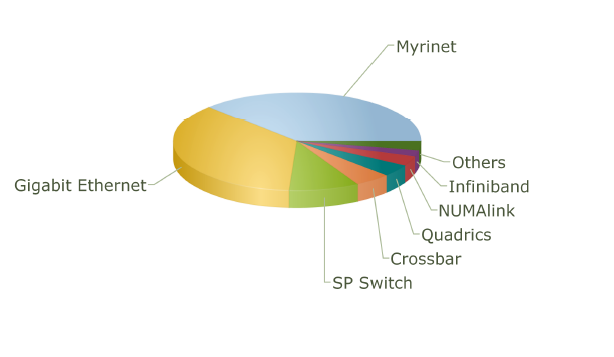

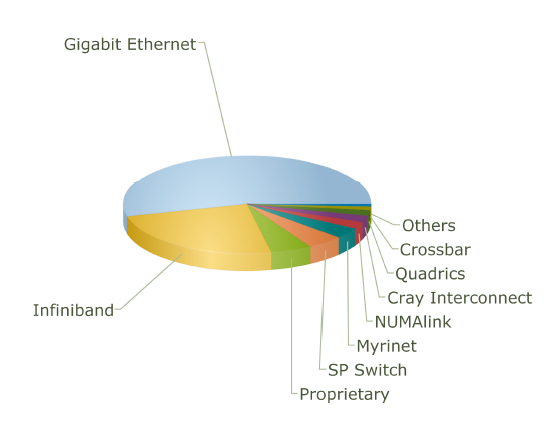

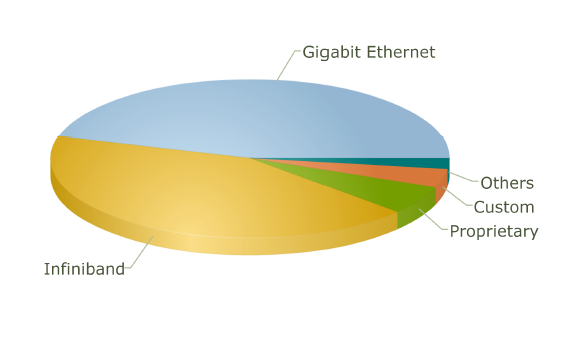

The use of different topologies has changed over the years. The following pie charts from top500.org show the share of different network topologies over the years. | The use of different topologies has changed over the years. The following pie charts from top500.org show the share of different network topologies over the years. | ||

[[Image:ob_wiki_12_2001.png | [[Image:ob_wiki_12_2001.png ]] ''Interconnect Family Market Share for 2001'' | ||

[[Image:ob_wiki_12_2004.png | [[Image:ob_wiki_12_2004.png]] ''Interconnect Family Market Share for 2004'' | ||

[[Image:ob_wiki_12_2007.png | [[Image:ob_wiki_12_2007.png]] ''Interconnect Family Market Share for 2007'' | ||

[[Image:ob_wiki_12_2010.png | [[Image:ob_wiki_12_2010.png]] ''Interconnect Family Market Share for 2010'' | ||

<h1> Performance Metrics for Interconnection Network Topologies</h1> | <h1> Performance Metrics for Interconnection Network Topologies</h1> | ||

| Line 586: | Line 584: | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

1 Solihin | [1] Yan Solihin, "Fundamentals of Parallel Computer Architecture: Multichip and Multicore Systems",2009. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

2 [http://www.ssrc.ucsc.edu/Papers/hospodor-mss04.pdf Interconnection Architectures for Petabyte-Scale High-Performance Storage Systems] | [2] Andy D. Hospodor and Ethan L. Miller, "[http://www.ssrc.ucsc.edu/Papers/hospodor-mss04.pdf Interconnection Architectures for Petabyte-Scale High-Performance Storage Systems]", In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE / 12th NASA Goddard Conference on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies,2004, pages 273--281. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

3 [http://www.diit.unict.it/~vcatania/COURSES/semm_05-06/DOWNLOAD/noc_routing02.pdf The Odd-Even Turn Model for Adaptive Routing] | [3] Ge-Ming Chiu; , "[http://www.diit.unict.it/~vcatania/COURSES/semm_05-06/DOWNLOAD/noc_routing02.pdf The Odd-Even Turn Model for Adaptive Routing]," Parallel and Distributed Systems, IEEE Transactions on , vol.11, no.7, pp.729-738, Jul 2000 | ||

doi: 10.1109/71.877831 | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

4 [http://www.csm.ornl.gov/workshops/IAA-IC-Workshop-08/documents/wiki/dally_iaa_workshop_0708.pdf Interconnection Topologies:(Historical Trends and Comparisons)] | [4] [http://www.csm.ornl.gov/workshops/IAA-IC-Workshop-08/documents/wiki/dally_iaa_workshop_0708.pdf Interconnection Topologies:(Historical Trends and Comparisons)] | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

5 [http://dspace.upv.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10251/2603/tesisUPV2824.pdf?sequence=1 Efficient mechanisms to provide fault tolerance in interconnection networks for PC clusters | [5] José Miguel Montañana Aliaga, "[http://dspace.upv.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10251/2603/tesisUPV2824.pdf?sequence=1 Efficient mechanisms to provide fault tolerance in interconnection networks for PC clusters]". | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

6 [http://web.ebscohost.com.www.lib.ncsu.edu:2048/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&hid=15&sid=72e3828d-3cb1-42b9-8198-5c1e974ea53f@sessionmgr4 Adaptive Fault Tolerant Routing Algorithm for Tree-Hypercube Multicomputer | [6] Qatawneh Mohammad, "[http://web.ebscohost.com.www.lib.ncsu.edu:2048/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&hid=15&sid=72e3828d-3cb1-42b9-8198-5c1e974ea53f@sessionmgr4 Adaptive Fault Tolerant Routing Algorithm for Tree-Hypercube Multicomputer]". | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

7 [http://www.top500.org TOP500 Supercomputing Sites] | [7] [http://www.top500.org TOP500 Supercomputing Sites] | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

Latest revision as of 16:22, 1 May 2011

Interconnection Network Architecture

In a multi-processor system, processors need to communicate with each other and access each other's resources. In order to route data and messages between processors, an interconnection architecture is needed.

Typically, in a multiprocessor system, message passed between processors are frequent and short1. Therefore, the interconnection network architecture must handle messages quickly by having low latency, and must handle several messages at a time and have high bandwidth.

In a network, a processor along with its cache and memory is considered a node. The physical wires that connect between them is called a link. The device that routes messages between nodes is called a router. The shape of the network, such as the number of links and routers, is called the network topology.

History of Network Topologies

The use of different topologies has changed over the years. The following pie charts from top500.org show the share of different network topologies over the years.

Interconnect Family Market Share for 2001

Interconnect Family Market Share for 2001

Interconnect Family Market Share for 2004

Interconnect Family Market Share for 2004

Interconnect Family Market Share for 2007

Interconnect Family Market Share for 2007

Interconnect Family Market Share for 2010

Interconnect Family Market Share for 2010

Performance Metrics for Interconnection Network Topologies

The several metrics used for evaluating characteristics of a network topology like latency, bandwidth, cost, etc. are as follows:

- Diameter: This is the longest distance between any pair of nodes of the network. It is measured in terms of network hops (the number of links the message must travel before reaching the destination).

- Bisection Bandwidth: This is the minimum number of links that one must cut in order to partition the network into two halves.

- Degree: This is the total number of links in and out from a router.

The Diameter and Bisection bandwidth are the measure of performance of a network while the degree along with the total number of links is the measure of cost.

Types of Network Topologies

Below are some of the common Network Topologies and their parameters for P nodes.

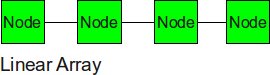

Linear Array

The nodes are connected linearly as in an array. This type of topology is simple, however, it does not scale well.

- Diameter: p-1

- Bisection BW: 1

- Number of Links: p-1

- Degree: 2

For a linear array, the diameter is nothing but the distance between the first and last node, i.e. one less than the total number of nodes. In order to cut the network into halves, we just need to cut one link in the center, and as seen in the diagram, the degree (number of links connected to one router) is 2.

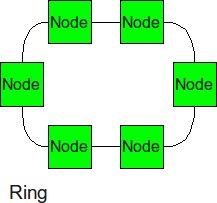

Ring

Similar structure as the linear array, except, the ending nodes connect to each other, establishing a circular structure. The longest distance between two nodes is cut in half.

- Diameter: p/2

- Bisection BW: 2

- Number of Links: p

- Degree: 2

For a ring, the diameter is nothing but the distance between two nodes across the diameter of the ring, i.e. half the total number of nodes. In order to cut the network into halves, we just need to cut two links across the ring diameter, and as seen in the diagram, the degree (number of links connected to one router) is 2.

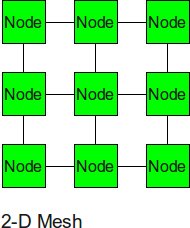

2-D Mesh

The 2-D mesh can be thought of as several linear arrays put together to form a 2-dimensional structure.

- Diameter: 2 x (sqrt(p) -1)

- Bisection BW: sqrt(p)

- Number of Links: 2 x sqrt(p) x (sqrt(p) -1 )

- Degree: 4

For a 2D Mesh, the diameter is nothing but the distance between two diagonally opposite corner nodes. If we have a total of P nodes, there are sqrt(P) nodes in each direction. Hence, there are sqrt(p) -1 links in each directions, giving us the resulting diameter of 2 x (sqrt(p) – 1). In order to cut the network into pieces, we just need to cut all links in one direction, i.e. one entire row or column, and one link in the other direction. This gives us the bisection bandwidth of sqrt(p) - 1 + 1 = sqrt(p). The degree is 4 as the nodes not at the edge have a total of 4 links connected to them.

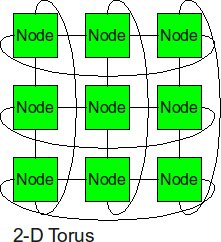

2-D Torus

The 2-D torus takes the structure of the 2-D mesh and connects the nodes on the edges.

- Diameter: (sqrt(p) -1) or sqrt(p)

- Bisection BW: 2 x sqrt(p) or 2 x (sqrt(p) + 1)

- Number of Links: 2 x sqrt(p) x (sqrt(p) -1 ) + 2 x sqrt(p)

- Degree: 4

The torus has links connecting the first and last nodes of each row and column to one another, which increases the total number of links in the system, but the diameter is now reduced. The diameter is the Distance between the center node of a perimeter row with the center node of as perimeter column which will be sqrt(p) or sqrt(p) -1 depending on whether the number of nodes in a row / column is even or odd. Similarly, we now have to cut twice the number of links compared to a Mesh, to bisect the network into two halves.

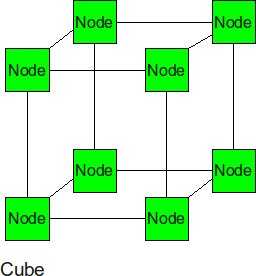

Cube

The cube can be thought of as a three-dimensional mesh.

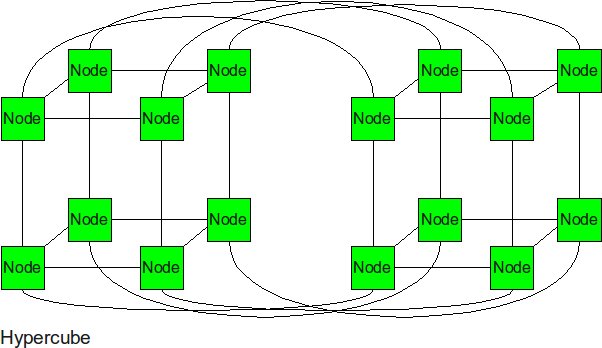

Hypercube

The hypercube is essentially multiple cubes put together.

- Diameter: log2(p)

- Bisection BW: p/2

- Number of Links: p/2 log2(p)

- Degree: log2(p)

If each node in the hypercube, is numbered using binary bits, each node is connected to all other nodes whose numbers differ from it in only one bit position. The distance between two binary numbers with farthest bits differing from each other (also known as [hamming distance]) is equal to the number of bits in its binary representation. For a hypercube of P nodes, this number is log2(p). The degree or number of links from a router is also equal to the number of bits in the binary representation. To bisect the hypercube, we need to cut 2^(log2(p) - 1) links which is equal to p /2.

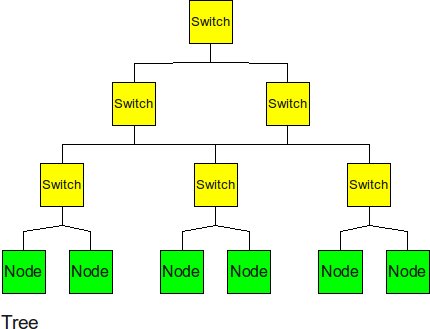

Tree

The tree is a hierarchical structure nodes on the bottom and switching nodes at the upper levels. The tree experiences high traffic at the upper levels.

- Diameter: 2logk(p)

- Bisection BW: 1

- Number of Links: k(p-1)

- Degree: k+1

For the tree, the diameter would be the distance between two leaf nodes. For a ‘’k-ary’’ tree , the height of the tree would be logk(p) and we would have to traverse from one leaf up to the root and back down, making the diameter 2 x logk(P). To cut the tree into half , all we need is to cut one link from the root. The degree is the number of links at the non leaf nodes of the tree, which is ‘’k+1’’.

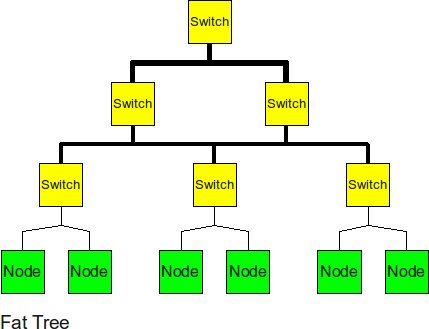

Fat Tree

The fat tree alleviates the traffic at upper levels by "fattening" up the links at the upper levels.

- Diameter: 2logk(p)

- Bisection BW: p/2

- Number of Links: k(p-1)

- Degree: k+1

The fat tree has similar characteristics to a k-ary tree, except for increasing the bisection BW to p/2 by making the links at the higher levels fatter than the leaf node links by a factor of the number of nodes below that link.

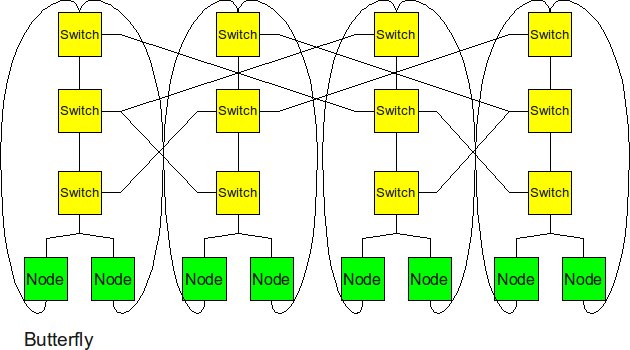

Butterfly

The butterfly structure is similar to the tree structure, but it replicates the switching node structure of the tree topology and connects them together so that there are equal links and routers at all levels.

- Diameter: log2(p)

- Bisection BW: p/2

- Number of Links: 2p x log2(p)

- Degree: 4

The butterfly network reduces the degree at each node since it is made up of multiple trees with each of the node interconnected across all levels.

Real-World Implementation of Network Topologies

In a research study by Andy Hospodor and Ethan Miller, several network topologies were investigated in a high-performance, high-traffic network2. Several topologies were investigated including the fat tree, butterfly, mesh, torii, and hypercube structures. Advantages and disadvantages including cost, performance, and reliability were discussed.

In this experiment, a petabyte-scale network with over 100 GBps total aggregate bandwidth was investigated. The network consisted of 4096 disks with large servers with routers and switches in between2.

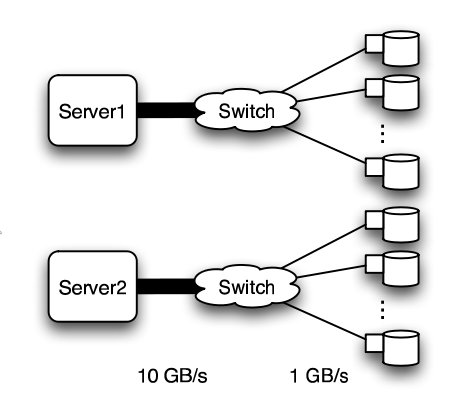

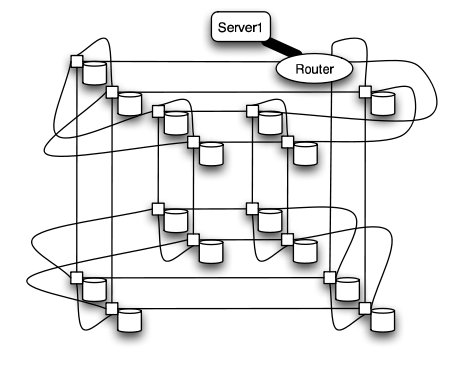

The overall structure of the network is shown below. Note that this structure is very susceptible to failure and congestion.

Basic structure of Hospodor and Miller's experimental network2

Fat Tree

In large scale, high performance applications, fat tree can be a choice. However, in order to "fatten" up the links, redundant connections must be used. Instead of using one link between switching nodes, several must be used. The problem with this is that with more input and output links, one would need routers with more input and output ports. Router with excess of 100 ports are difficult to build and expensive, so multiple routers would have to be stacked together. Still, the routers would be expensive and would require several of them2.

The Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology supercomputing system uses the fat tree topology. The system connects 1280 processors using NEC processors7.

Butterfly

In high performance applications, the butterfly structure is a good choice. The butterfly topology uses fewer links than other topologies, however, each link carries traffic from the entire layer. Fault tolerance is poor. There exists only a single path between pairs of nodes. Should the link break, data cannot be re-routed, and communication is broken2.

Butterfly structure2

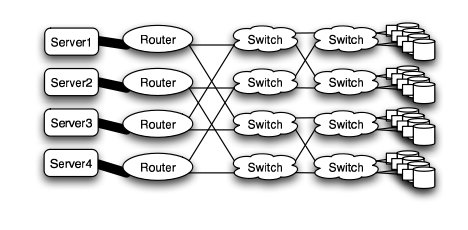

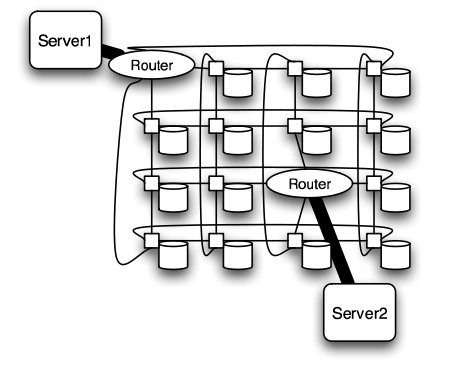

Meshes and Tori

The mesh and torus structure used in this application would require a large number of links and total aggregate of several thousands of ports. However, since there are so many links, the mesh and torus structures provide alternates paths in case of failures2.

Some examples of current use of torus structure include the QPACE SFB TR Cluster in Germany using the PowerXCell 8i processors. The systems uses 3-D torus topology with 4608 processors7.

Mesh structure2

Torus structure2

Hypercube

Similar to the torii structures, the hypercube requires larger number of links. However, the bandwidth scales better than mesh and torii structures.

The CRAY T3E, CRAY XT3, and SGI Origin 2000 use k-ary n-cubed topologies.

Hypercube structure2

Comparison of Network Topologies

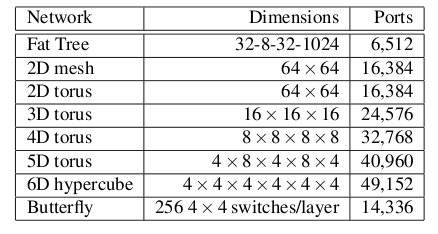

The following table shows the total number of ports required for each network topology.

Number of ports for each topology2

As the figure above shows, the 6-D hypercube requires the largest number of ports, due to its relatively complex six-dimensional structure. In contrast, the fat tree requires the least number of ports, even though links have been "fattened" up by using redundant links. The butterfly network requires more than twice the number of ports as the fat tree, since it essentially replicates the switching layer of the fat tree. The number of ports for the mesh and torii structures increase as the dimensionality increases.

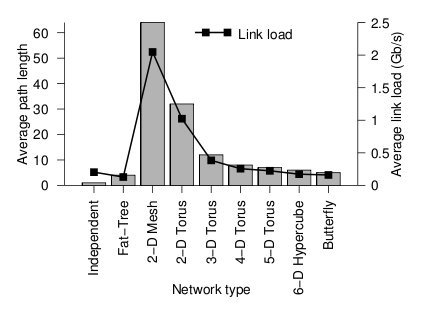

Below the average path length, or average number of hops, and the average link load (GB/s) is shown.

Average path length and link load for each topology2

Looking at the trends, when average path length is high, the average link load is also high. In other words, average path length and average link load are proportionally related. It is obvious from the graph that 2-D mesh has, by far, the worst performance. In a large network such as this, the average path length is just too high, and the average link load suffers. For this type of high-performance network, the 2-D mesh does not scale well. Likewise the 2-D torus cuts the average path length and average link load in half by connected the edge nodes together, however, the performance compared to other types is relatively poor. The butterfly and fat-tree have the least average path length and average link load.

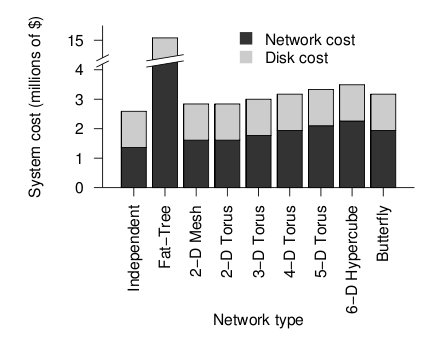

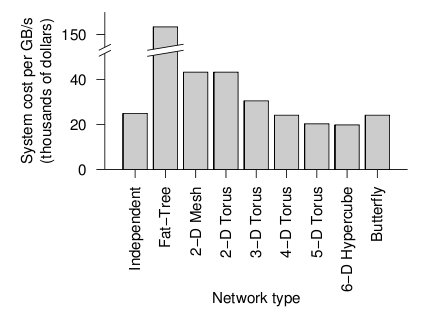

The figure below shows the cost of the network topologies.

Cost of each topology2

Despite using the fewest number of ports, the fat tree topology has the highest cost, by far. Although it uses the fewest ports, the ports are high bandwidth ports of 10 GB/s. Over 2400, ports of 10 GB/s are required have enough bandwidth at the upper levels of the tree. This pushes the cost up dramatically, and from a cost standpoint is impractical. While the total cost of fat tree is about 15 million dollars, the rest of the network topologies are clustered below 4 million dollars. When the dimensionalality of the mesh and torii structures increase, the cost increases. The butterfly network costs between the 2-D mesh/torii and the 6-D hypercube.

When the cost and average link load is factored the following graph is produced.

Overall cost of each topology2

From the figure above, the 6-D hypercube demonstrates the most cost effective choice on this particular network setup. Although the 6-D hypercube costs more because it needs more links and ports, it provides higher bandwidth, which can offset the higher cost. The high dimensional torii also perform well, but cannot provide as much bandwidth as the 6-D hypercube. For systems that do not need as much bandwidth, the high-dimensional torii is also a good choice. The butterfly topology is also an alternative, but has lower fault tolerance.

Why do 2D meshes dominate?

From the perspective of performance and flexibility for each of the topologies, it looks like higher dimension networks are preferable compared to low dimensional networks. However, in reality, cost of building the network is also an important consideration. In a 2D network, each router is very simple since it only needs to have a degree of 4. A router usually uses crossbar switches to route inputs to outputs and the cost of additional ports increase the complexity quadratically.

In comparison to a 2D mesh, a router for a hypercube is much more complex with a degree of twice the diameter. For example, for 5 dimensions, we need a router of degree 10. With other networks like a butterfly, the complexity of a router remains same at 4 but we would need a larger number of routers as the number of links is more.

Routing

The routing algorithm determines what path a packet of data will take from source to destination. Routing can be deterministic, where the path is the same given a source and destination, or adaptive, where the path can change. The routing algorithm can also be partially adaptive where packets have multiple choices, but does not allow all packets to use the shortest path3.

Deadlock

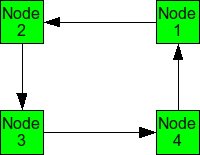

When packets are in deadlock when they cannot continue to move through the nodes. The illustration below demonstrates this event.

Example of deadlock

Assume that all of the buffers are full at each node. Packet from Node 1 cannot continue to Node 2. The packet from Node 2 cannot continue to Node 3, and so on. Since packet cannot move, it is deadlocked.

The deadlock occurs from cyclic pattern of routing. To avoid deadlock, avoid circular routing pattern.

To avoid circular patterns of routing, some routing patterns are disallowed. These are called turn restrictions, where some turns are not allowed in order to avoid making a circular routing pattern. Some of these turn restrictions are mentioned below.

Dimensional ordered (X-Y) routing

Turns from the y-dimension to the x-dimension are not allowed.

West First

Turns to the west are not allowed.

North Last

Turns after a north direction are not allowed.

Negative First

Turns in the negative direction (-x or -y) are not allowed, except on the first turn.

Odd-Even Turn Model

Unfortunately, the above turn-restriction models reduce the degree of adaptiveness and are partially adaptive. The models cause some packets to take different routes, and not necessarily the minimal paths. This may cause unfairness but reduces the ability of the system to reduce congestion. Overall performance could suffer3.

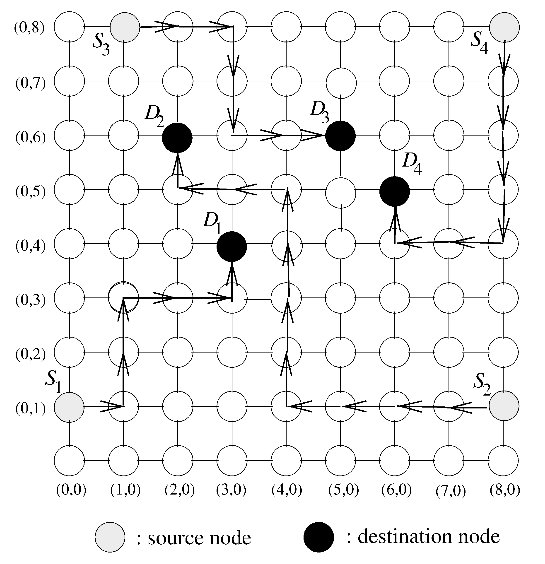

Ge-Ming Chiu introduces the Odd-Even turn model as an adaptive turn restriction, deadlock-free model that has better performance than the previously mentioned models3. The model is designed primarily for 2-D meshes.

Turns from the east to north direction from any node on an even column are not allowed.

Turns from the north to west direction from any node on an odd column are not allowed.

Turns from the east to south direction from any node on an even column are not allowed.

Turns from the south to west direction from any node on an odd column are not allowed.

The illustration below shows allowed routing for different source and destination nodes. Depending on which column the packet is in, only certain directions are allowed.

Odd-Even turn restriction model proposed by Ge-Ming Chiu3

Comparison of Turn Restriction Models

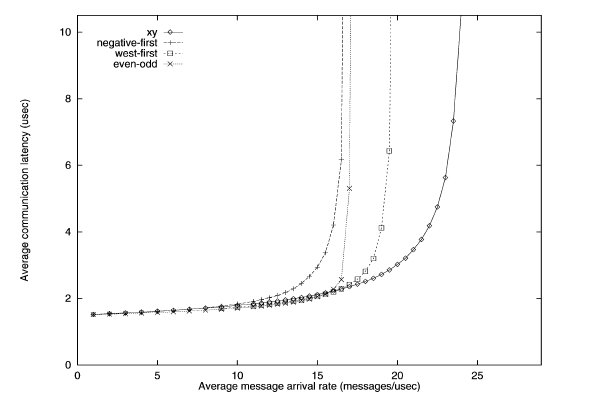

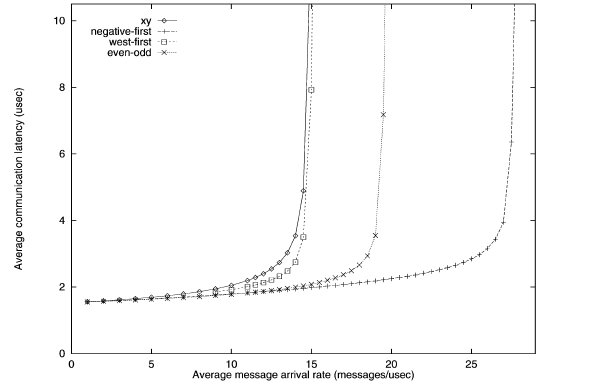

To simulate the performance of various turn restriction models, Chiu simulated a 15 x 15 mesh under various traffic patterns. All channels have bandwidth of 20 flits/usec and has a buffer size of one flit. The dimension-ordered x-y routing, west-first, and negative-first models were compared against the odd-even model.

Traffic patterns including uniform, transpose, and hot spot were conducted. Uniform simulates one node send messages to any other node with equal probability. Transpose simulates two opposite nodes sending messages to their respective halves of the mesh. Hot spot simulates a few "hot spot" nodes that receive high traffic.

Uniform traffic simulation of various turn restriction models3

The performance of the different routing algorithms is shown above for the uniform traffic. For uniform traffic, the dimensional ordered x-y model outperforms the rest of the models. As the number of messages increase, the x-y model has the "slowest" increase in average communication latency.

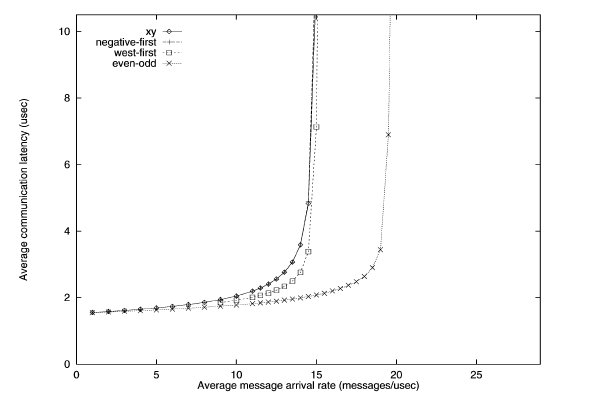

First transpose traffic simulation of various turn restriction models3

The performance of the different routing algorithms is shown above for the first transpose traffic. The negative-first model has the best performance, while the odd-even model performs better than the west-first and x-y models.

Second transpose traffic simulation of various turn restriction models3

With the second transpose simulation, the odd-even model outperforms the rest.

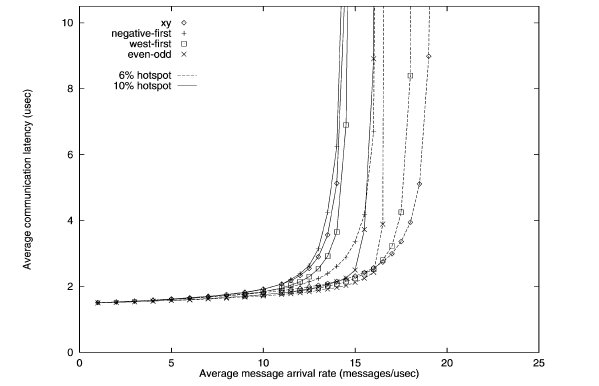

Hotspot traffic simulation of various turn restriction models3

The performance of the different routing algorithms is shown above for the hotspot traffic. Only one hotspot was simulated for this test. The performance of the odd-even model outperforms other models when hotspot traffic is 10%.

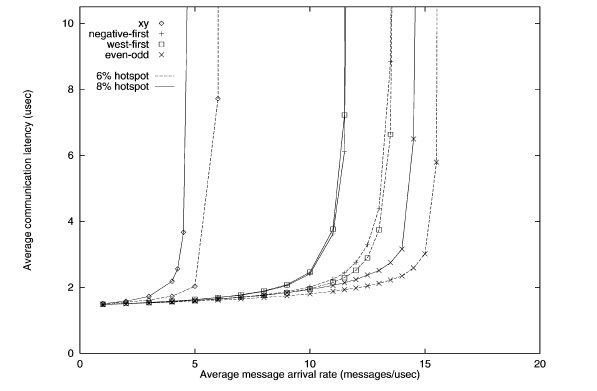

Second hotspot traffic simulation of various turn restriction models3

When the number of hotspots is increased to five, the performance of the odd-even begins to shine. The latency is lowest for both 6 and 8 percent hotspot. Meanwhile, the performance of x-y model is horrendous.

While the x-y model performs well in uniform traffic, it lacks adaptiveness. When traffic becomes hotspot, the x-y model suffers from the inability to adapt and re-route traffic to avoid the congestion caused by hotspots. The odd-even model has superior adaptiveness under high congestion.

Router Architecture

The router is a device that routes incoming data to its destination. It does this by having several input ports and several output ports. Data incoming from one of the inputs ports is routed to one of the output ports. Which output port is chosen depends on the destination of the data, and the routing algorithms.

The internal architecture of a router consists of input and output ports and a crossbar switch. The crossbar switch connects the selects which output should be selected, acting essentially as a multiplexer.

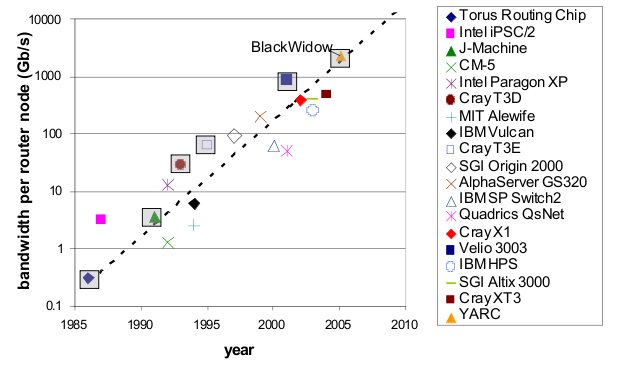

Router technology has improved significantly over the years. This has allowed networks with high dimensionality to become feasible. As shown in the real-world example above, high dimensional torii and hypercube are excellent choice of topology for high-performance networks. The cost of high-performance, high-radix routers has contributed to the viability of these types of high dimensionality networks. As the graph below shows, the bandwidth of routers has improved tremendously over a period of 10 years4.

Bandwidth of various routers over 10 year period4

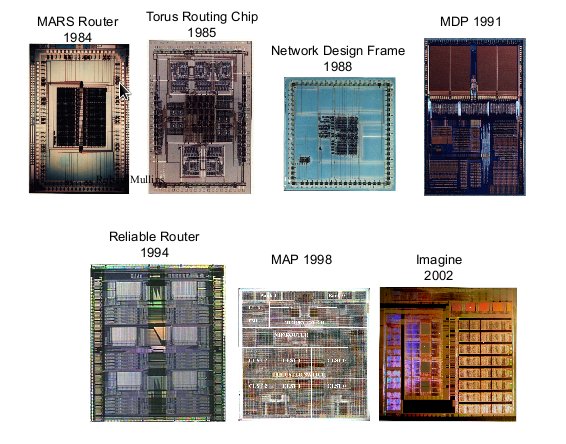

Looking at the physical architecture and layout of router, it is evident that the circuitry has been dramatically more dense and complex.

Router hardware over period of time4

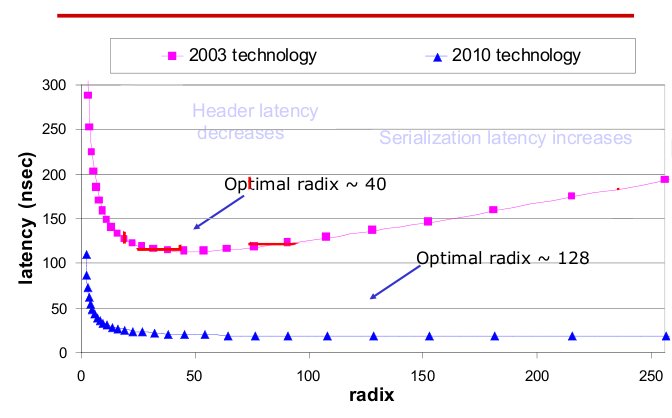

Radix and latency of routers over 10 year period4

The radix, or the number of ports of routers has also increased. The current technology not only has high radix, but also low latency compared to last generation. As radix increases, the latency remains steady.

With high-performance routers, complex topologies are possible. As the router technology improves, more complex, high-dimensionality topologies are possible.

Fault Tolerant Routing

Fault-tolerant routing means the successful routing of messages between any pair of non faulty nodes in the presence of faulty components6. With increased number of processors in a multiprocessor system and high data rates reliable transmission of data in event of network fault is of great concern and hence fault tolerant routing algorithms are important.

Fault Models

Faults in a network can be categorized in two types:

1.Transient Faults5 : A transient fault is a temporary fault that occurs for a very short duration of time. This fault can be caused due to change in output of flip-flop leading to generation of invalid header. These faults can be minimized using error controlled coding. These errors are generally evaluated in terms of Bit Error Rate.

2.Permanent Faults5: A permanent fault is a fault that does not go away and causes a permanent damage to the network. This fault could be due to damaged wires and associated circuitry. These faults are generally evaluated in terms of Mean Time between Failures.

Fault Tolerance Mechanisms (for permanent faults)

The permanent faults can be handled using one of the two mechanisms:

1.Static Mechanism: In static fault tolerance model, once the fault is detected all the processes running in the system are stopped and the routing tables are emptied. Based on the information of faults the routing tables are re-calculated to provide a fault free path.

2.Dynamic Mechanisms: In dynamic fault tolerance model, it is made sure that the operation of the processes in the network is not completely stalled and only the affected regions are provided cure. Some of the methods to do this are:

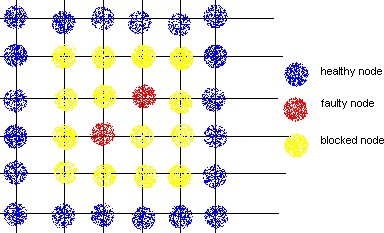

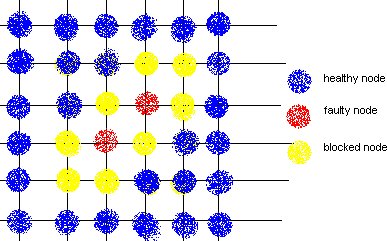

a.Block Faults: In this method many of the healthy nodes in vicinity of the faulty nodes are marked as faulty nodes so that no routes are created close to the actual faulty nodes. The shape of the region could be convex or non-convex, and is made sure that none of the new routes introduce cyclic dependency in the cyclic dependency graph (CDG).

DISADVANTAGE: This method causes lot of healthy nodes to be declared as faulty leading to reduction in system capacity.

b.Fault Rings: This method was introduced by Chalasani and Boppana. A fault tolerant ring is a set of nodes and links that are adjunct to faulty nodes/links. This approach reduces the number of healthy nodes to be marked as faulty and blocking them.

References

[1] Yan Solihin, "Fundamentals of Parallel Computer Architecture: Multichip and Multicore Systems",2009.

[2] Andy D. Hospodor and Ethan L. Miller, "Interconnection Architectures for Petabyte-Scale High-Performance Storage Systems", In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE / 12th NASA Goddard Conference on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies,2004, pages 273--281.

[3] Ge-Ming Chiu; , "The Odd-Even Turn Model for Adaptive Routing," Parallel and Distributed Systems, IEEE Transactions on , vol.11, no.7, pp.729-738, Jul 2000

doi: 10.1109/71.877831

[4] Interconnection Topologies:(Historical Trends and Comparisons)

[5] José Miguel Montañana Aliaga, "Efficient mechanisms to provide fault tolerance in interconnection networks for PC clusters".

[6] Qatawneh Mohammad, "Adaptive Fault Tolerant Routing Algorithm for Tree-Hypercube Multicomputer".

[7] TOP500 Supercomputing Sites