CSC/ECE 517 Fall 2012/ch2a 2w26 aj: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

The article is intended to be an accompaniment to the SaaS video lecture 4.6 titled “Enhancing Rotten Potatoes again” <ref name="video">Enhancing Rotten Potatoes again, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l9uLw3y6J8<br></ref>, part of the SaaS video lecture series for the Software Engineering for SaaS hosted on the Coursera learning network. <ref>Coursera, https://www.coursera.org/</ref><br>The Rotten Potatoes webpage, designed in the previous lectures is enhanced for implementing a new feature to add a new movie by looking up the TMDb database<ref> TMDb — The Movie Database, http://www.themoviedb.org/</ref> rather than manually entering the movie name. The flow of this article is as follows : | |||

*The scope of discussion | |||

*Brief description of the storyboard used for the Lo-Fi UI design discussed in previous lectures in the video lecture series, | |||

*Explanation of Sad path, Happy Path and Bad Path | |||

*Description of the User Story developed in the video lecture | |||

*Elaboration of the test scenarios written for the particular User story (including scenarios for happy and sad paths) in Cucumber | |||

*Explanation of the Background facility in Cucumber | |||

== | ==Scope== | ||

The scope of this article is limited only to the scope covered in the video lecture. The lecture builds upon Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) basics discussed in the video lectures before it and sets the reader up for upcoming lectures concerning Test-Driven Development (TDD). Hence for the purpose of this article, it is assumed that the reader has already read the material and watched the video lectures before this one in the series. Hence the setup for Cucumber, Capybara and BDD basics are excluded from this article. The resources dealing with these can be found in the SaaS lectures 4.1 to 4.5 in the series. Similarly, the theory and implementation of TDD as well as further discussion on BDD is excluded from the scope of this article. More details on these can be found in lectures 4.7 to 5.11 of the SaaS lecture series .<ref>Software Engineering for SaaS, https://class.coursera.org/saas-2012-003/class/index </ref> | |||

== | ==A Brief Recap== | ||

Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) is a specialized development process which concentrates more on the behavioral aspects of the application as against the actual implementation of the application. <ref>Software Engineering for SaaS, https://class.coursera.org/saas-2012-003/class/index </ref> | |||

Storyboards are used to show how UI changes based on user actions. Even if it is tedious to draw sketches and storyboards, it helps build a ‘bigger picture’ understanding of the flow of the application for the non-technical stakeholders. | |||

Cucumber is one of the shining tools of Rails that is used for testing purposes. It acts as a halfway between the customer and the developer by converting user stories of 3x5 cards into tests. | |||

These tests act as Acceptance tests for ensuring the satisfaction of the customer. Also, the tests act as Integration tests that ensures the communication between modules is consistent and correct | |||

==The User Story== | |||

The aim of the User story described in the video is to add a new feature to the Rotten Potatoes web page, to add a new movie to the movies list on Rotten Potatoes page. But, for adding the movie to the list, it populates the data from TMDb rather than entering the information by hand. This is aimed at reducing repetitive work since the TMDb already has a good database of movies. | |||

To do so, the ability to search TMDb from Rotten Potatoes home page needs to be incorporated in the webpage. Users can then search in TMDb if the movie is present in it and then its details can be imported into Rotten Potatoes. For integrating this feature into the application, first, a Lo-Fi UI and Storyboard is designed, which is described next. | |||

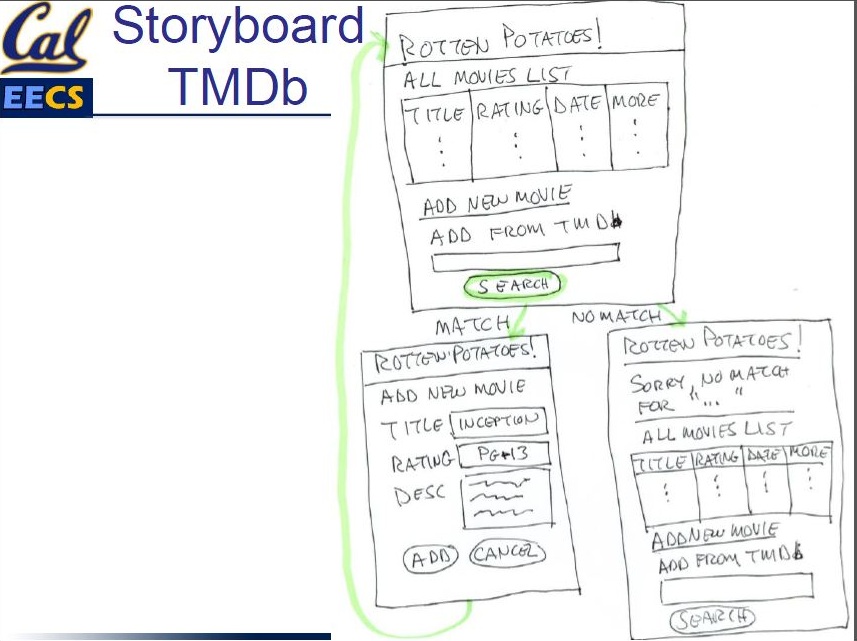

==The StoryBoard== | |||

The Storyboard is to be interpreted as follows | |||

When a person wants to add a new movie to the Movies list on Rotten Potatoes, he/she will enter the new movie name and click “Search”. The controller method should search the TMDb database for the given movie. If a match is found, i.e. the movie is present in the TMDb, then the “Match” page is displayed. If there is no match, otherwise “No Match” page is displayed. These two scenarios, are the Happy Path and Sad Path implementations respectively. | |||

[[File:Storyboard.jpg|200 px|thumb|Center|The Storyboard for the User Story. (Click Image to expand) ]] | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

== Further Reading == | == Further Reading == | ||

Revision as of 01:20, 27 October 2012

SaaS 4.6 Enhancing Rotten Potatoes again

Introduction

The article is intended to be an accompaniment to the SaaS video lecture 4.6 titled “Enhancing Rotten Potatoes again” <ref name="video">Enhancing Rotten Potatoes again, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l9uLw3y6J8

</ref>, part of the SaaS video lecture series for the Software Engineering for SaaS hosted on the Coursera learning network. <ref>Coursera, https://www.coursera.org/</ref>

The Rotten Potatoes webpage, designed in the previous lectures is enhanced for implementing a new feature to add a new movie by looking up the TMDb database<ref> TMDb — The Movie Database, http://www.themoviedb.org/</ref> rather than manually entering the movie name. The flow of this article is as follows :

- The scope of discussion

- Brief description of the storyboard used for the Lo-Fi UI design discussed in previous lectures in the video lecture series,

- Explanation of Sad path, Happy Path and Bad Path

- Description of the User Story developed in the video lecture

- Elaboration of the test scenarios written for the particular User story (including scenarios for happy and sad paths) in Cucumber

- Explanation of the Background facility in Cucumber

Scope

The scope of this article is limited only to the scope covered in the video lecture. The lecture builds upon Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) basics discussed in the video lectures before it and sets the reader up for upcoming lectures concerning Test-Driven Development (TDD). Hence for the purpose of this article, it is assumed that the reader has already read the material and watched the video lectures before this one in the series. Hence the setup for Cucumber, Capybara and BDD basics are excluded from this article. The resources dealing with these can be found in the SaaS lectures 4.1 to 4.5 in the series. Similarly, the theory and implementation of TDD as well as further discussion on BDD is excluded from the scope of this article. More details on these can be found in lectures 4.7 to 5.11 of the SaaS lecture series .<ref>Software Engineering for SaaS, https://class.coursera.org/saas-2012-003/class/index </ref>

A Brief Recap

Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) is a specialized development process which concentrates more on the behavioral aspects of the application as against the actual implementation of the application. <ref>Software Engineering for SaaS, https://class.coursera.org/saas-2012-003/class/index </ref>

Storyboards are used to show how UI changes based on user actions. Even if it is tedious to draw sketches and storyboards, it helps build a ‘bigger picture’ understanding of the flow of the application for the non-technical stakeholders.

Cucumber is one of the shining tools of Rails that is used for testing purposes. It acts as a halfway between the customer and the developer by converting user stories of 3x5 cards into tests. These tests act as Acceptance tests for ensuring the satisfaction of the customer. Also, the tests act as Integration tests that ensures the communication between modules is consistent and correct

The User Story

The aim of the User story described in the video is to add a new feature to the Rotten Potatoes web page, to add a new movie to the movies list on Rotten Potatoes page. But, for adding the movie to the list, it populates the data from TMDb rather than entering the information by hand. This is aimed at reducing repetitive work since the TMDb already has a good database of movies. To do so, the ability to search TMDb from Rotten Potatoes home page needs to be incorporated in the webpage. Users can then search in TMDb if the movie is present in it and then its details can be imported into Rotten Potatoes. For integrating this feature into the application, first, a Lo-Fi UI and Storyboard is designed, which is described next.

The StoryBoard

The Storyboard is to be interpreted as follows When a person wants to add a new movie to the Movies list on Rotten Potatoes, he/she will enter the new movie name and click “Search”. The controller method should search the TMDb database for the given movie. If a match is found, i.e. the movie is present in the TMDb, then the “Match” page is displayed. If there is no match, otherwise “No Match” page is displayed. These two scenarios, are the Happy Path and Sad Path implementations respectively.

<references/>

Further Reading

Wikipedia - Closures : everything there is to know about Closures on one page.

Reg Braithwaite - Closures and Higher-Order Functions : gives Ruby examples of specialized Closures.

Closures in Ruby : gives a detailed explanation of Closures in Ruby.

MSDN Magazine - Functional Programming .NET Development : examples of functional style with Closures in C#.

Eric Kidd - Some useful closures, in Ruby : demonstrates more examples of curried and specialized Closures in Ruby.

Jim Weirich - Top Ten Reasons I Like Ruby - Blocks and Closures : provides several examples of how Closures can be useful in Ruby.

C# in Depth - The Beauty of Closures : demonstrates Closures in C#.

Martin Fowler - Closure : provides a basic definition of Closures and gives a few very basic examples.

Javascript Closures : demonstrates Javascript Closures in callbacks.

Alan Skorkin - Closures - A Simple Explanation : gives a high-level overview of Closures using Ruby examples.

IBM Developerworks - Crossing borders : Closures : gives Ruby examples where Closures are useful.

Sam Danielson - An Introduction to Closures in Ruby : high-level overview of using Closures in Ruby.